Physiological route for fluid intake

Less risk of tissue trauma

Home therapy possible

Rapid administration

No use in cases of digestive tract disease

May damage stomach if the stomach tube is inserted too roughly

Rehydration rates are slow

Risk of aspiration pneumonia

Limited volumes may be administered at any one time

Rapid administration possible, minimizing stress

Uptake may be better than oral in cases of digestive tract disease

Minimal risk of internal organ damage during administration

Risk of muscle and subcutaneous tissue trauma

Rates of rehydration poor if severely dehydrated and peripheral vessels are collapsed

Only isotonic or hypotonic fluids may be administered

Darkening of the skin at the injection site particularly in lizards such as iguanas and chameleons

Uptake is faster than subcutaneous

Minimally painful route of administration

Rehydration rates may still be slow in severe cases of dehydration

Only isotonic or hypotonic fluids may be administered

Increased risk of organ damage

Colloidal and hypertonic fluids and blood transfusions possible

Use of intravenous catheters and syringe drivers makes for accurate delivery

Species of reptile (e.g., snakes) may make venous access difficult without minor surgery

Veins are more fragile than mammalian vessels

Increased skill levels and equipment required

Colloidal and hypertonic fluids and blood transfusions possible

Use of intraosseous catheters and syringe drivers makes for accurate delivery

Useful in smaller species or species where venous access is difficult

Sedation, local or general anaesthesia is required for catheter insertion

Tolerance may be poor in some species

Oral

Snakes

The oral route is not useful for seriously debilitated animals, but is for those with pharyngostomy feeding tubes in place, or if the owner or handler is experienced in stomach tubing. Mild cases of dehydration, where owners wish to home treat their pet, are ideal. A stomach tube is passed by restraining the snake’s head gently but firmly, and then inserting a plastic or wooden tongue depressor to open the mouth. A lubricated feeding tube is then passed through the labial notch (the area at the most rostral aspect of the mouth without teeth) and to a depth of one third of the snake’s length.

Lizards

Gavage (stomach) tubes or avian straight crop tubes or straightforward feeding tubes can be used to administer fluids directly into the oesophagus or stomach. The reptile needs to be firmly restrained to keep the head and oesophagus in a straight line. The mouth is opened with a plastic or wooden tongue depressor and the tube inserted to a depth of one third to one half the torso length of the reptile. This method is often stressful for the reptile. The alternative is to syringe fluids into the mouth, but this risks inhalation in a debilitated reptile. A pharyngostomy tube may be placed for nutritional support, and so may be used for fluid therapy.

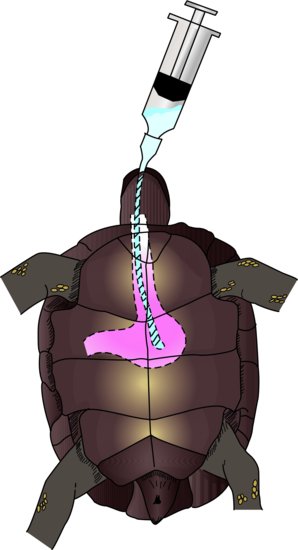

Chelonians

An oesophagostomy tube may be implanted as described below, and levels of 10 mL/kg at any one time can be administered. Alternatively, a stomach tube may be inserted each time it is needed. The feeding tube is first measured from the tip of the extended nose to the line where the pectoral and abdominal ventral scutes connect. It can then be lubricated and passed after extending the head and gently prising the mouth open with a wooden or plastic speculum (Figure 22.1).

Placement of oesophagostomy tubes

Oesophagostomy tubes may be placed in any species of reptile, but are particularly useful in chelonians which can retract its head deep inside its shell, making repeated stomach tubing impossible. It also significantly reduces the stress and trauma of repeatedly passing a stomach tube in long-term anorectic reptile patients.

The steps for placement are as follows:

NB: The tube should be measured prior to implantation so the depth of insertion is known. It is measured in tortoises from the site of the tube incision to the mid-portion of the plastron, halfway through the abdominal scutes. A further length should then be allowed, in order to attach the end of the feeding tube to the dorsal aspect of the carapace.

Figure 22.2 (a) An oesophagostomy tube in place in an anorectic leopard tortoise (Stigmochelys pardalis). (b) An oesophagostomy tube in place in an anorectic green iguana (Iguana iguana).

Subcutaneous

Snakes

The lateral aspect of the dorsum of the snake, in the caudal third of its body, is the ideal site for subcutaneous fluid administration. This is a good technique for use for routine post-operative administration of fluids to patients undergoing minor surgical procedures such as skin mass removals. If positioned correctly, there is a lymph sinus running lateral to the epaxial muscles on either side, just subcutaneously, which can be used for moderately large volumes. It may, however, still be necessary to use several sites.

Lizards

The lateral thoracic area is easily used for smaller volumes of fluids at any one site. There is a risk of the reptile developing a darkened, pigmented area over the injection site, particularly in chameleons.

Chelonians

The subcutaneous route is easily used for post-operative fluids and mild dehydration in this species. Fluids may be given in the area just cranial to the hind limbs, or in the skin folds just lateral to the neck. Relatively large volumes may be given via this route.

Intracoelomic

Snakes

The intracoelomic route is useful for more seriously dehydrated reptiles, as there is a greater vasculature at this site for absorption. The needle or butterfly catheter is inserted two rows of lateral scales dorsal to the ventral scutes in the caudal third of the snake, but cranial to the vent. The needle is inserted so that it just penetrates the body wall, the plunger of the syringe is pulled back to ensure no organ puncture has occurred and the fluids administered. If correctly inserted, there will be no resistance to the injection.

Lizards

Because of the positioning necessary for administration, the intracoelomic route may be a stressful method of fluid administration. As for small mammals, the lizard should be placed in dorsal recumbency with its head downwards to encourage the gut contents to fall cranially and away from the injection site. The needle, preferably 25 gauge or smaller, is advanced slowly to just pop through the abdominal wall in the lower right ventral quadrant. The syringe plunger should be pulled back to ensure that no organ has been penetrated, and the fluids can be administered without any resistance.

Chelonians

The intracoelomic route can be used in tortoises up to a maximum of 20–25 mL/kg/day only; otherwise, due to the confines of the rigid shell, the fluids will place too much pressure on the lung fields. The area cranial to the hind limbs is used, that is, the same site as for subcutaneous routes, but the chief difference is depth. The concern with this route is that the bladder lies in this area, and if full may be punctured. The other route is the cranial access site. This is located lateral to the neck and medial to the front limb and is more epicoelomic than truly intracoelomic. The needle is kept close and parallel to the plastron and a 3/4-inch needle may be inserted to the level of the hub.

Intravenous

Snakes

There are no major vessels for intravenous use in snakes which are easily accessible. If an intravenous route is to be used, one of the following is required.

Ventral tail vein

This is more of a plexus of veins, and may be accessed from the ventrum. The needle is inserted midline, one-third of the tail length from the vent, and advanced until it touches the coccygeal vertebrae at a 90-degree angle. The needle is then retracted slightly whilst drawing back on the syringe until blood flows into the hub. Fluids may then be given slowly.

Palatine vein

This is present on the roof of the mouth, as its name suggests, and is paired. Cannulation may be performed with a 25–27 gauge butterfly catheter although the snake has to be sedated or anaesthetised to gain access.

Jugular vein

These can only be accessed in an anesthetised or sedated snake. A full-thickness skin cut-down procedure is performed 5–7.5 cm caudal to the angle of the jaw, two rows of scales dorsal to the ventral scutes. The jugular vein can then be seen medial to the ribs. An over-the-needle catheter is best for this, and should then be sutured in place.

Intracardiac

This site can be used in emergencies. The heart may be catheterised under sedation or anaesthesia only. On turning the snake onto its back, the heart may be seen to beat against the ventral scale, approximately one quarter of its length from the snout. A 25–27 gauge over-the-needle catheter may be inserted between the scales, ventrally, in a caudocranial manner at 30 degrees to the body wall into the single ventricle. A bolus may be administered, or it may be taped, glued or sutured in place for 24–48 hours.

Lizards

The intravenous route can be difficult in small lizards, and frequently requires sedation or anaesthesia. Several veins may be tried.

Cephalic vein

This is approached in the anaesthetised lizard by performing a cut-down procedure on the cranial aspect of the middle of the antebrachium, perpendicular to the long axis of the radius and ulna. The vessel may then be catheterised using an over-the-needle catheter, which is then sutured in place. This technique is really only useful for lizards over 0.25 kg in weight.

Jugular vein

This vessel may be accessed via a cut-down technique in the anaesthetised or sedated lizard. An incision is made in a craniocaudal direction 2.5 cm caudal to the angle of the jaw. An over-the-needle catheter may then be sutured in place.

Ventral tail vein

This is more of a plexus of veins. It is accessed from the ventral aspect of the tail and can be performed in the conscious lizard. It is frequently only suitable for one-off bolus injections, and special care should be taken with species which exhibit autotomy (spontaneous tail shedding). The needle is inserted at 90 degrees to the angle of the tail and advanced until it touches the coccygeal vertebrae. It is then withdrawn slightly while drawing back on the syringe. When blood flows into the syringe, the infusion may begin (Figure 22.3).

Chelonians

There are two main intravenous routes: the dorsal tail vein and the jugular veins.

Jugular vein

These may be accessed for catheter placement in the sedated or anaesthetised tortoise. The neck is extended and the head tilted away from the operator to push the neck towards him or her. The jugular vein runs from the dorsal aspect of the eardrum along the more dorsal aspect of the neck (Figure 22.4). An over-the-needle catheter may be placed directly, or, in thicker-skinned animals, a cut-down technique employed.

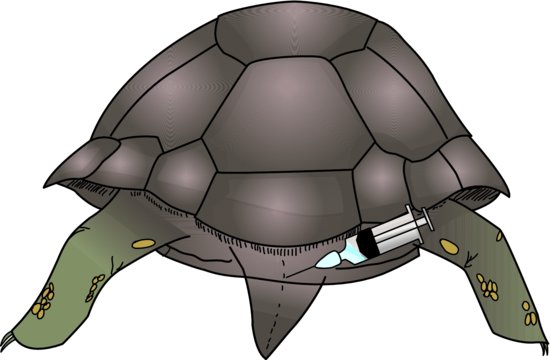

Figure 22.4 Placement of a jugular catheter in a chelonian. Note the taping of the drip tubing to the dorsal carapace midline and the attachment to the syringe driver.

Dorsal tail vein

This is more of a plexus of veins. Therefore it is often not possible to give large volumes of fluids, and certainly not possible to place a catheter. Access is midline, on the dorsal aspect of the tail. The needle is inserted at a 90-degree angle until it hits the coccygeal vertebrae. The needle is then pulled back, drawing back on the syringe at the same time, until blood flows into the hub (Figure 22.5).

Intraosseous

Snakes

The intraosseous route is not possible in the snake.

Lizards

The intraosseous is a good route for smaller species of lizards, where venous access is restricted or difficult. There are a few access points to choose from. Hypodermic or spinal needles of 23–25 gauge sizes may be used.

Proximal femur

This may be accessed from the fossa created between the greater trochanter and the hip joint. This route may be difficult due to the 90-degree angle the femur often forms with the pelvis.

Distal femur

This is relatively easy to access from above the stifle joint. It does restrict the movement of the stifle, but it is easier to bandage the catheter into this site and access to the medullary cavity of the femur is certainly easier via this route. Sedation or anaesthesia is required. See below for the placement technique.

Proximal tibia

This again is possible in the larger species. Anaesthesia and sedation is needed, and the spinal needle or hypodermic needle may be screwed into the tibial crest region in a proximodistal manner.

Placement of distal femoral intraosseous catheters in lizards (Figure 22.6)

Figure 22.6 Distal femoral intraosseous fluid administration in an inland bearded dragon (Pogona vitticeps).

The technique for placement of a distal femoral intraosseous catheter in a lizard is explained in detail below.

Chelonians

Two main intraosseous sites can be used.

Plastrocarapacial junction/pillar

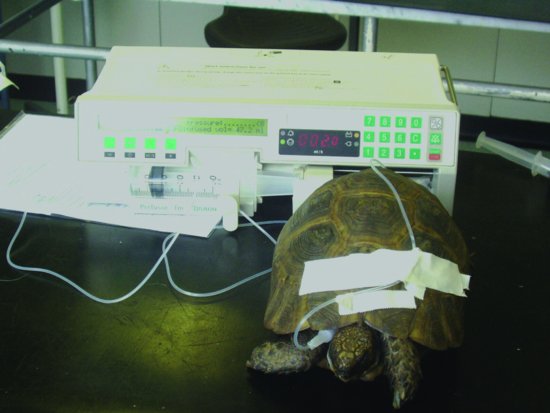

This is the pillar of shell which connects the plastron to the carapace. It is approached from the caudal aspect, just cranial to one of the hind limbs. The spinal or hypodermic needle (21–23 gauge) is screwed into the shell attempting to keep the angle of insertion parallel with the outer wall of the shell, so entering the shell bone marrow cavity (Figure 22.7). In larger, older species, the shell may be too tough to allow penetration.

Figure 22.7 Intraosseous fluid administration via the plastrocarapacial pillars. Note the syringe driver in background.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree