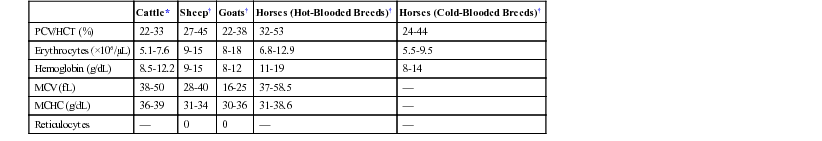

Leslie C. Sharkey, Jed A. Overmann *, Consulting Editors The erythron is defined as the total mass of circulating erythrocytes and their precursors within the bone marrow. Alterations in the erythron are common in clinical practice and developing an approach to interpreting these abnormalities is important. Initial assessment of the erythron is generally accomplished through evaluation of a complete blood cell count (CBC). Major alterations include anemia and erythrocytosis. Based on the results of the CBC, clinical history, and physical examination, additional diagnostic tests can then be selected to further characterize these abnormalities in an attempt to identify a specific underlying pathophysiologic process. Erythrocytes are produced in the bone marrow, largely under the influence of erythropoietin (EPO), with increased erythropoiesis occurring in response to blood loss or hemolysis. Horses are unique in that equine erythrocytes generally remain in the bone marrow until fully mature before they are released into circulation. As a result, peripheral indicators of regeneration used in other species such as polychromasia and reticulocytosis are typically absent or unreliable in the horse. Detection of relatively low numbers of reticulocytes in the peripheral blood of anemic horses, however, has been described using an automated hematology analyzer, which may be a more sensitive means of detecting these cells than the manual methods used previously.1,2 General reference intervals are presented for common erythrocyte parameters in large animals (Table 24-1); however, laboratory- or instrument-specific reference intervals should be used whenever possible. A complete discussion of age- and breed-related influences on erythrocyte parameters is found elsewhere.3–5 What follows is a brief review of common laboratory evaluators of the erythron. TABLE 24-1 Reference Intervals for Ruminants and Horses * From George JW, Snipes J, Lane M. 2010. Comparison of bovine hematology reference intervals from 1957-2006. Vet Clin Pathol 39:138. † From Jain NC. 1986. Schalm’s veterinary hematology, ed 4. Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia, PA. Hematocrit (HCT), packed cell volume (PCV), hemoglobin (Hgb) concentration, and red blood cell (RBC) count are all ways of quantifying the erythrocytes in peripheral blood, and these measures tend to increase (erythrocytosis) or decrease (anemia) together. HCT and PCV are similar in that they are describing the percentage volume of whole blood occupied by erythrocytes. The HCT is a calculated value and is a function of the mean cell volume and RBC count, whereas the PCV is determined by centrifugation of whole blood in a microhematocrit tube. The Hgb concentration and RBC count are measured values generated by hematology analyzers. The mean cell volume (MCV) is directly measured by most hematology analyzers and represents the average erythrocyte volume. An increased MCV can be the result of a regenerative anemia in the ruminant and occasionally in the horse. Decreased MCV is seen with iron-deficiency anemia (also copper) and can also be seen in healthy calves and foals.3,4 The mean cell hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) is the cellular Hgb concentration per average erythrocyte and is calculated from the Hgb concentration and HCT. A decreased MCHC can be seen in ruminants with regenerative anemias, but this would not be expected in the horse. Both horses and ruminants can have decreased MCHC as the result of iron-deficiency anemia. A low MCHC has also been reported in calves (<5 weeks) as an age-related change.6 Increased MCHC values are almost always false increases and can be seen with hemolyzed, severely icteric, or lipemic samples, or those with large numbers of Heinz bodies present. Mean cell hemoglobin (MCH) is the amount of hemoglobin per average erythrocyte (in picograms). This is a calculated value based on the Hgb concentration and the RBC count. In general, MCH is affected in a similar manner to MCHC. MCHC, however, is considered more useful since it takes into account cell volume and is thus preferred over MCH when evaluating the erythron. Anisocytosis is variation in erythrocyte size. A mild to moderate degree of anisocytosis can be seen in healthy ruminants, whereas mild anisocytosis can be seen in healthy horses. Increased anisocytosis can be the result of a regenerative anemia in ruminants and occasionally in horses. The RBC distribution width (RDW) provides an index of the variation in erythrocyte size. Polychromatophilic erythrocytes are slightly immature, macrocytic cells that appear blue-gray on a Wright-stained blood smear because of their retained cytoplasmic RNA. An increase in these cells in the peripheral blood is indicative of a regenerative response in ruminants. Increased polychromasia is not expected in horses because in this species erythrocytes complete maturation in the bone marrow prior to release into circulation. Polychromatophilic erythrocytes are relatively analogous to reticulocytes; however, not all reticulocytes will be viewed as polychromatophilic erythrocytes on a peripheral blood smear. Thus, a reticulocyte count is considered a more objective and sensitive means of detecting a regenerative response, particularly if performed by an automated hematology analyzer. If a reticulocyte count is not available, a moderate to large degree of polychromasia observed on a peripheral blood smear is a good indicator of a regenerative response in ruminants. Howell-Jolly bodies are small, dark, circular structures consisting of nuclear material within erythrocytes. These can be present in small numbers in healthy horses. Increased numbers can be associated with regenerative anemias and splenic dysfunction. Note that in cattle Howell-Jolly bodies can appear similar to Anaplasma marginale and can be difficult to differentiate from these organisms in some cases. Nucleated erythrocytes (nRBCs) are not normally seen in the peripheral blood of healthy horses or ruminants. In ruminants, small numbers associated with regenerative anemias can sometimes be present, but should be accompanied by a significant degree of polychromasia. Bone marrow damage (e.g., toxic damage, hypoxia, neoplasia) can also result in circulating nRBCs. The presence of nRBCs and basophilic stippling in the absence of significant anemia should prompt consideration of lead toxicity (more common in ruminants). Basophilic stippling is seen as multiple small basophilic inclusions within erythrocytes and is the result of staining of ribosomal aggregates. Basophilic stippling is often seen in association with regenerative anemias in ruminants. As described previously, it can also be seen in cases of lead toxicity. Heinz bodies form in erythrocytes as a result of oxidative damage that leads to precipitation of Hgb. They are recognized on Wright-stained blood smears as rounded, pale pink staining structures that protrude from the edge of erythrocytes. Heinz bodies can be confirmed by visualizing them with use of a new methylene blue stain that stains Heinz bodies as dark, rounded structures associated with the erythrocyte membrane. Ingestion of oxidants such as wilted red maple leaves, onions, and garlic; phenothiazine; Brassica spp.; and copper toxicity can result in Heinz body formation in large animals. Heinz body formation causes affected erythrocytes to be more susceptible to both intravascular and extravascular hemolysis. Eccentrocytes also form as a result of oxidative damage. In the case of eccentrocytes, oxidative damage results in partial fusion of the erythrocyte membrane causing displacement of Hgb contents to one side of the erythrocyte. Oxidants listed as causes of Heinz bodies can also result in eccentrocyte formation. Eccentrocytes have also been reported in horses with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency and flavin adenine dinucleotide deficiency. Both are rare erythrocyte enzyme deficiencies that result in the affected animal’s erythrocytes being more susceptible to oxidative damage by endogenous or exogenous sources.7

Alterations in the Erythron

Erythropoiesis

Laboratory Evaluation of Erythrocytes

Cattle*

Sheep†

Goats†

Horses (Hot-Blooded Breeds)†

Horses (Cold-Blooded Breeds)†

PCV/HCT (%)

22-33

27-45

22-38

32-53

24-44

Erythrocytes (×106/µL)

5.1-7.6

9-15

8-18

6.8-12.9

5.5-9.5

Hemoglobin (g/dL)

8.5-12.2

9-15

8-12

11-19

8-14

MCV (fL)

38-50

28-40

16-25

37-58.5

—

MCHC (g/dL)

36-39

31-34

30-36

31-38.6

—

Reticulocytes

—

0

0

—

—

Hematocrit, Packed Cell Volume, Hemoglobin Concentration, and RBC Count

Mean Cell Volume

Mean Cell Hemoglobin Concentration and Mean Cell Hemoglobin

Erythrocyte Morphology

Anisocytosis.

Polychromasia.

Howell-Jolly Bodies.

Nucleated Erythrocytes.

Basophilic Stippling.

Heinz Bodies.

Eccentrocytes.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Alterations in the Erythron

Chapter 24