Chapter 20 Allergic Airway Disease In Dogs And Cats And Feline Bronchopulmonary Disease

PARASITIC ALLERGIC AIRWAY DISEASE

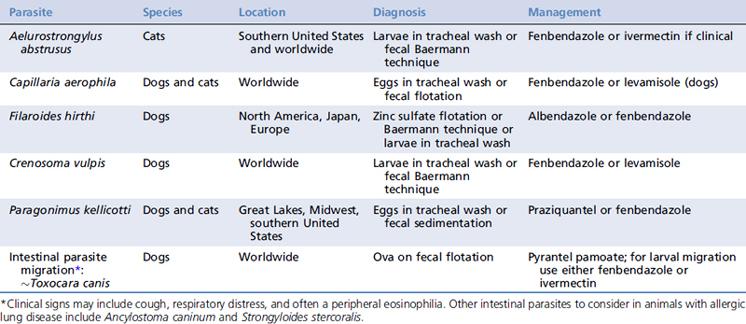

Other, less common parasites known to migrate through the lungs include Ancylostoma caninum (dogs only) and Strongyloides stercoralis (dogs or cats). Primary lung parasites include Paragonimus kellicotti, Aelurostrongylus abstrusus, Capillaria aerophila, and Filaroides hirthi (Table 20-1). Dirofilaria immitis (heartworm infection) can also cause an allergic inflammatory response when large numbers of antimicrofilarial antibodies entrap microfilariae within the pulmonary capillaries.12 All of these parasites elicit predominantly a type I hypersensitivity reaction in the lungs that leads to bronchoconstriction and inflammation within the airways and lung parenchyma.11

Initially, a course of an appropriate antihelminthic medication (ivermectin or fenbendazole) can be used for treatment, particularly in mild to moderate clinical cases (see Table 20-1). Appropriate treatment for infection with D. immitis is discussed elsewhere.14 In situations in which the clinical signs are severe, or fail to resolve completely, an antiinflammatory dosage of prednisone (0.5 to 1 mg/kg q24h) may be used to help control the disease manifestations.10,11

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree