Chapter 4 Alimentary disorders

Introduction

Chapter 4 illustrates those conditions with primary alimentary signs. It excludes congenital (e.g., cleft palate) and acquired neonatal conditions (e.g., calfhood enteritis). The first section comprises infectious and contagious diseases: bovine virus diarrhea/mucosal disease (BVD/MD) complex, vesicular stomatitis, papular stomatitis (all of which have rather similar gross features), and paratuberculosis. The second section covers the alimentary parasitic conditions: ostertagiasis, and small and large intestinal parasitism (for coccidiosis, see 2.31, 2.32). The remaining conditions are listed by anatomical site (oral cavity to anus), irrespective of their traumatic, nutritional, or other etiology.

Viral diseases

Three viral diseases present problems clinically in differential diagnosis: bovine virus diarrhea/mucosal disease (BVD/MD), vesicular stomatitis, and bovine papular stomatitis. In some regions, further differential diagnosis from foot-and-mouth disease and rinderpest may be necessary (see 12.2–12.15). The pathogenicity and economic importance of these vesicular viral diseases vary greatly. Accurate differentiation is essential and usually depends on laboratory studies.

Bovine virus diarrhea/mucosal disease (BVD/MD)

Clinical features

BVD/MD is a major viral disease worldwide. Congenital defects such as cerebellar hypoplasia and cataracts (8.1, 8.4) may develop in the progeny of females infected during early pregnancy. BVD/MD causes diarrhea and unthriftiness in young cattle. Erosive stomatitis and rhinitis occur, together with similar lesions on other mucous membranes.

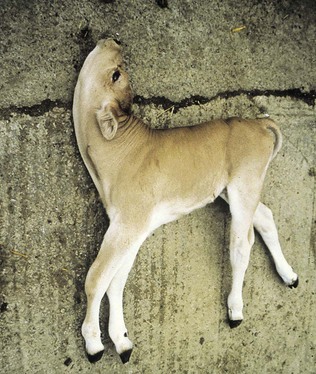

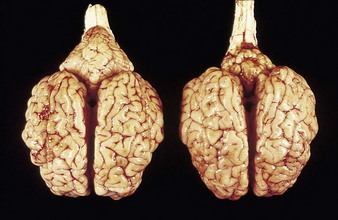

In utero infection in the first trimester can produce early embryonic death and infertility, and in the early to midfetal period congenital abnormalities such as cerebellar hypoplasia or, less commonly, hydranencephaly, as in the Piedmontese calf in 4.1. Though alert, and suckling with difficulty, it was unable to stand. It was relatively normal at rest, but extensor spasm and opisthotonus developed on minimal stimulation, e.g., when attempting to feed. Cerebellar hypoplasia was confirmed at autopsy examination. 4.2 shows a normal brain (left) and the affected brain (following infection of the dam at 150 days’ gestation).

In utero infection in the second trimester, before the age of immunological competence of the fetus, can lead to the birth of a persistently infected calf which is BVD antigen positive, but antibody negative. Such animals may be either clinically normal or stunted, but they continually excrete virus. Unpredictable nervous signs such as aggression may be seen in some BVD persistent infection (P1) calves. At a later date, usually 3–30 months old, superinfection with a noncytopathic strain of BVD virus leads to a syndrome of mucosal disease, with ulceration throughout the gastrointestinal tract. Clinically these animals present signs of oral, intestinal and respiratory involvement. Erosions and hyperemia around the nares, lips, and gums are seen in 4.3.

The specimen in 4.4 shows numerous erosive and hemorrhagic lesions over the entire hard palate. Secondary bacterial infection of the lesions produces the necrotic ulcers seen in the caudal pharynx and rima glottidis (4.5). Necrosis and abscessation surround the epiglottis. The laryngeal mucosa is also hemorrhagic. Pus lies between the arytenoids, making respiratory efforts difficult and painful. Similar necrotic ulcers may extend over the hard palate, down the esophagus and into the abomasum. The esophagus may have patchy, linear areas of hemorrhage, edema and erosions. Erosions may be seen on the edematous and hyperemic edges of the abomasal rugae (4.6). Small intestinal erosions can lead to mucosal sloughing and the production of casts that pack the intestinal lumen (4.7). A secondary bacterial infection may be responsible for the enlarged nodes. Erosions may also occur around the coronary band and in the interdigital cleft (4.8).

The two cattle in 4.9 are both 18 months old. The nearer heifer, with an abnormal, rust-colored coat, is stunted as a result of chronic, persistent infection (antigen positive, antibody negative) due to maternal infection with BVD virus acquired in early pregnancy. Many of the mucosal changes are so severe as to leave the chronic, persistent infective case emaciated (as in the crossbred animal in 4.10) and a constant source of infection to susceptible contact cattle.

Differential diagnosis

salmonellosis, paratuberculosis (4.16), winter dysentery (4.19, 4.20) and other causes of acute enteritis in individuals. Bovine papular stomatitis (4.13), vesicular stomatitis (4.12), FMD (12.2–12.8) and other causes of oral ulceration.

Vesicular stomatitis

Clinical features

the Charolais calf shows blanched areas on the rugae of the hard palate, dental pad, and gums (4.11). These pale areas are vesicles that rupture after some days (4.12). Secondary infection is rare. Vesicular stomatitis has only been confirmed in North and South America. Many animals may be simultaneously affected on one farm, showing excessive salivation, together with oral and possibly teat lesions. Teat lesions (11.26) in vesicular stomatitis can cause problems with milking. Secondary lesions may involve the claws.

Differential diagnosis

foot-and-mouth disease (12.2–12.8) and bovine papular stomatitis (4.13, 4.14). Diagnosis by ELISA or CF test, and if negative, following passage, virus neutralization tests.

Bovine papular stomatitis (BPS)

Clinical features

shallow papules and vesicles are seen on the muzzle, hard palate and gums of these young cattle (4.13, 4.14). Papules develop a distinct roughened center that sometimes expands to merge with adjacent vesicles. A Hereford crossbred calf (4.15) also shows muzzle and nares with ruptured vesicles. Teats are not affected. Immature cattle, sometimes an entire group, are usually involved and recovery is rapid. Systemic effects are rare.

Johne’s disease (paratuberculosis)

Definition

chronic wasting disease caused by Mycobacterium avium paratuberculosis (formerly M. johnei).

Clinical features

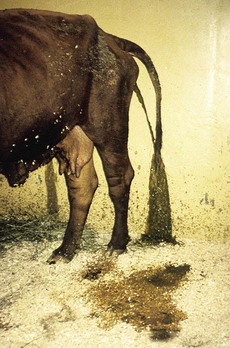

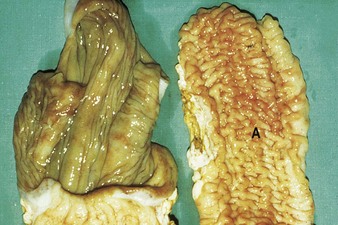

Johne’s disease causes progressive weight loss, leading to eventual emaciation, although animals may remain alert and continue to eat. This chronic wasting disease is characterized by a profuse, watery diarrhea as seen in an 8-year-old Santa Gertrudis cow (4.16). Clinical signs of wasting and watery diarrhea are evident in a 2-year-old Blonde d’Aquitaine bull (4.17). When compared with normal ileum (4.18), the mucosa in a clinically overt case (A) shows numerous, thick, transverse rugae that cannot be smoothed out by stretching. Local intestinal lymph nodes are usually enlarged and pale, and may contain granulomatous areas. The usual age range is 3–9 years for the onset of clinical signs, which may be insidious, or develop suddenly after calving. Carrier animals excrete for many months prior to this. Infection is introduced into healthy herds by subclinical carriers. Young calves become infected in utero, via colostrum, or by oral ingestion. Age immunity develops by 4–6 months old.

Winter dysentery (winter diarrhea)

Clinical features

a watery diarrhea (4.19) lasting about 3 days, winter dysentery causes a sporadic problem in adult dairy cattle. Spontaneous recovery usually takes place after a few days. Some animals show profuse intestinal hemorrhage, passing large quantities of fresh blood in feces (4.20), and suffer a severe production drop, though deaths are rare. Seroconversion to coronavirus can be used for diagnosis, although many animals in a herd are already seropositive.

Repeated outbreaks are possibly due to the presence of carrier animals.

Differential diagnosis

Johne’s disease (4.16), rumenitis or overeating (4.56), BVD, salmonellosis, bovine influenza A (diarrhea with respiratory signs), PPH (9.39).

Gastrointestinal parasitism

Ostertagiasis

Clinical features

cattle are most commonly affected with a chronic, persistent diarrhea and weight loss during their first season at pasture. Type I disease caused by Ostertagia ostertagi results from the ingestion of large numbers of L3 larvae from herbage, starting 3–6 weeks before the onset of clinical signs. Small nodules that are 1–2 mm in diameter are present on and between the abomasal folds on the mucosal surface (4.21). In severe cases a “Morocco leather” or “cobblestone” appearance is evident (4.22). Higher magnification of a severe case shows the thickened rugae (ridges) and the white worms (4.23). Marked edema of the gastrointestinal wall is often present. Type II disease occurs when larvae ingested in the autumn lie dormant in the abomasal glands (as L4), and then emerge en masse in late winter or early spring to produce a profuse scour and weight loss in housed cattle. Note the weight loss, chronic diarrhea, and tenesmus in an older Charolais heifer (4.24).

Oesophagostomum infection

Clinical features

4.25 shows the serosal surface of the distal small intestine. Numerous caseated and calcified nodules indicate the presence of Oesophagostomum radiatum (nodular worm 12–15 mm long) in an older, resistant animal.

Dental problems

Clinical features

dental problems are not a common cause of clinical disease in cattle. Occasionally, when the temporary incisors are being replaced by the permanent dentition, 2–3-year-old heifers show difficulty in prehension (4.26) leading to excessive salivation and weight loss. Diets such as heavily impacted self-feed silage leading to excessive incisor wear (4.27) may cause progressive weight loss. The crowns have almost disappeared, resulting in impairment of the animal’s foraging ability. Shedding teeth (4.28) can lead to temporary dysphagia and impaired weight gain.

Fluorosis

Fluorosis (4.29) leads to mottling and excessive wear of temporary teeth during their development. The more severe fluorine-induced discoloration (4.30) should be differentiated from the staining caused by ingestion of some forms of grass silage. Other signs of fluorosis are seen in 13.31 and 13.32.

Irregular molar wear

Irregular molar wear can sometimes cause masticatory problems. When eating or ruminating, this 8-year-old bull (4.31) occasionally kept the jaws apart as a result of “locking” the overgrown lingual edge of the upper molars and premolars against the buccal edge of the mandibular cheek teeth. The length of the bilaterally symmetrical overgrowth was about 1 cm. 4.31 shows the typical open “locked” position.

Mandibular fracture

Clinical features

mandibular fractures can occur in calves being kicked by cows or occasionally from iatrogenic trauma, e.g., from farm machinery. In the mature Friesian cow (4.32) with the symphysial fracture, the central incisor was displaced. There was little separation of the two halves of the mandible. A considerable quantity of saliva is being lost. In this case the cause was unknown, and full recovery occurred without treatment.

Discrete swellings of the head

Actinobacillosis, actinomycosis, and local abscessation related to Arcanobacterium pyogenes can present similar clinical features in some cattle. Typically, however, actinobacillosis affects the soft tissues, especially the tongue, while actinomycosis involves bone. Abscessation related to tooth root infection is rare in cattle. A curious disorder or vice of habitual tongue playing, not involving any oral pathology, is shown in 4.33. This Guernsey cow lost a considerable volume of saliva through drooling.

Actinobacillosis (“wooden tongue”)

Clinical features

Actinobacillus lignieresii preferentially colonizes the soft tissues of the head, especially the tongue. External swelling beneath the jaw may be seen (4.34). It typically causes a localized, firm swelling of the dorsum (D), as in this dairy cow (4.35) and firm, easily palpable, subepithelial masses elsewhere. Actinobacillosis with severe swelling of the tongue may result in its chronic protrusion (4.36). Other parts of the head, such as the nares or facial skin, are sometimes alone affected. Infection may pass down the esophagus, and lesions in the esophageal groove typically cause vomiting of rumen contents or bloat. Other areas of the body (e.g., the limbs (4.37) face and head (4.38), or flanks) may develop cutaneous actinobacillosis. Skin infection usually follows trauma and exposure to a concentrated infective dose of organisms, which are part of the normal flora of the upper GI tract. Such massive lesions are particularly liable to bleed and ulcerate. Most cases tend to occur in mature cattle of dairy breeds.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree