Chapter 6 Acquired Valvular Disease

DEGENERATIVE MITRAL VALVE DISEASE

Prevalence and Incidence

• Degenerative valvular disease is uncommon in cats, and when it occurs it seldom results in clinical consequences.

Pathology

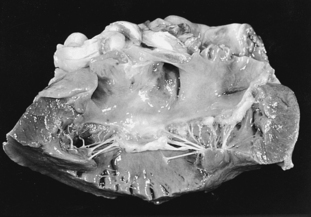

• Grossly, MVD is characterized by nodular distortion of the valve leaflets as well as by thickening and, sometimes, lengthening of the chordae tendineae. The appearance of a small number of nodules at the free edge of the valve leaflet is the initial pathology. As the disease progresses, these nodules increase in number and size and coalesce. In severe cases, the leaflets are contracted, and the free edge of the leaflet rolls inward toward the ventricular endocardium (Figure 6-1). When severe, these abnormalities prevent coaptation of the valve leaflets, resulting in mitral valve incompetence.

Pathophysiology

• The initiation of valve closure is a passive process; in early systole, when left ventricular pressure exceeds left atrial pressure, the mitral valve leaflets are forced into apposition. In normal individuals, the tethering effect of the chordae tendineae prevents prolapse, or bowing, of the leaflets into the left atrium.

Clinical Presentation

History

• MVD exhibits a broad spectrum of severity. In most affected dogs, MVD does not cause clinical signs, and the disease is detected when a cardiac murmur is incidentally identified in patients presented for routine health care or for management of noncardiac disease.

Physical Findings

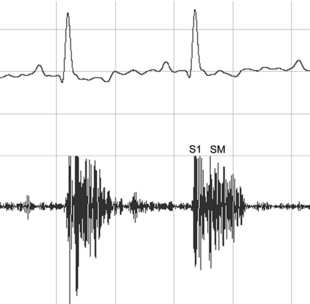

• The most notable feature of the physical examination is a systolic murmur that is usually heard best over the left cardiac apex. The murmur of MVD is indistinguishable from the murmur caused by other disorders, such as IE or dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), which also can result in MR. Importantly, however, an acquired, left apical, systolic murmur in an older, small-breed dog is almost always due to MVD. The intensity of the murmur depends on a number of factors, but severe MR usually causes a loud murmur. Severe MR associated with a nonrestrictive regurgitant orifice can result in a soft murmur but this is extremely uncommon in MVD. Phonocardiographically, the murmur of MR typically has a plateau-shaped configuration meaning that the murmur has a similar intensity throughout systole; when the murmur is loud, the second heart sound may be obscured (Figure 6-2).

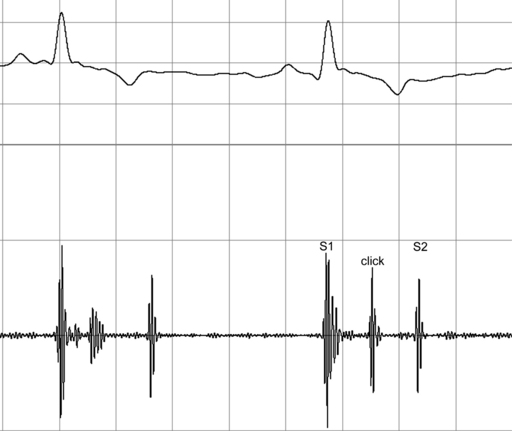

• A high-frequency, mid-systolic click (Figure 6-3) is sometimes heard in older, small-breed dogs. These clicks may be associated with prolapse of the mitral valve. In many dogs, clicks are a precursor of MR. Often, a soft systolic murmur of MR can also be heard in patients that have systolic clicks.

• Crackles may be heard in patients with pulmonary edema. It should be recognized that the prevalence of primary respiratory diseases such as chronic bronchitis in the patients most often affected by MVD is relatively high. Primary respiratory tract diseases can explain adventitious pulmonary sounds, such as crackles, in the absence of pulmonary edema.

Patients with Mitral Regurgitation and Concurrent Respiratory Tract Disease

• Coughing in elderly, small-breed dogs that do not have cardiac murmurs is almost always due to primary respiratory tract disease (Table 6-1).

Table 6-1 Guidelines for Clinical Assessment of Elderly Small-Breed Dogs With Cough and Cardiac Murmur*

| Cardiac Disease | Respiratory Disease | |

|---|---|---|

| Body condition | Thin | Obese |

| Cardiac murmur | Loud | Often soft, occasionally loud |

| Heart rate | Rapid | Normal or slow |

| Rhythm | Regular, unless pathologic arrhythmias are present | Exaggerated respiratory arrhythmia may be present |

Diagnostic Findings

Radiographic Appearance of Left Atrial Enlargement

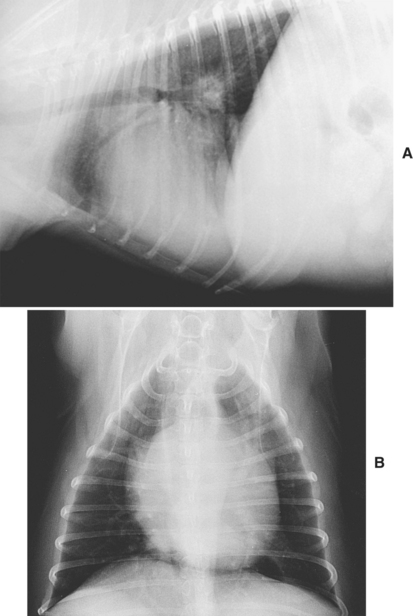

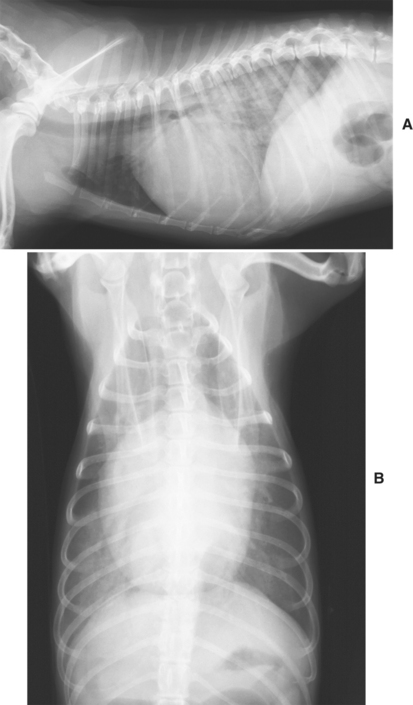

• In the ventrodorsal projection, the left atrium is located near the center of the cardiac silhouette. When enlarged, the left atrium splits the mainstem bronchi to varying degrees. This is apparent in well-penetrated radiographs and results in an appearance that is sometimes known as the “crab sign” or the “bowlegged cowboy” (Figures 6-4 and 6-5).

Radiographic Findings of Pulmonary Congestion and Edema

• The radiographic finding of pulmonary venous distention reflects increases in pulmonary venous pressure. Pulmonary venous distention suggests pulmonary congestion and may precede the development of pulmonary edema.

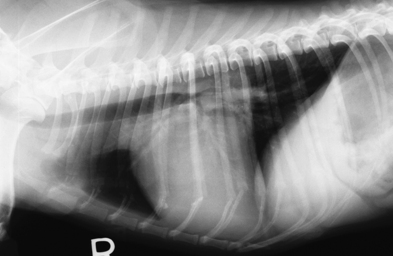

• When tissue fluid weeps into the pulmonary alveoli, it provides contrast with air-filled structures such as the bronchi, resulting in air bronchograms. Alveolar pulmonary opacities together with radiographic evidence of left atrial enlargement are diagnostic of left-sided CHF (Figure 6-6). The presence of alveolar pulmonary edema indicates severe CHF that is almost invariably associated with noticeable respiratory distress.

Key Point

In most cases, thoracic radiography is the most important aspect of the diagnostic approach to MVD.

Echocardiography

• Echocardiographic examination of patients with MVD demonstrates variable degrees of left atrial (Figure 6-7) and left ventricular dilation. Hypertrophy is usually adequate to preserve a near-normal relationship between the diastolic luminal dimension and wall thickness.

• The mitral leaflets may be noticeably thicker than normal, and prolapse of the leaflets into the left atrium in systole is commonly observed (Figure 6-8).

• Evaluation of myocardial function in patients with MR is difficult. When MR is moderate or severe, loading conditions imposed on the left ventricle are altered and left ventricular performance is hyperdynamic (Figure 6-9) provided myocardial function (contractility) is preserved.

• Ejection phase indices of systolic performance such as fractional shortening are elevated because these variables are highly load-dependent. When MR is present, impedance to ventricular emptying is reduced because the ventricle is able to eject blood into the low-pressure reservoir of the left atrium. Additionally, end-diastolic ventricular stretch associated with MR increases the force of contraction and contributes to the finding of hyperdynamic ventricular performance. A normal or subnormal fractional shortening in the setting of moderate or severe MR suggests systolic myocardial dysfunction (Figures 6-10 and 6-11).

• Doppler evidence of disturbed flow within the left atrium during systole is noninvasive confirmation of the presence of MR (see Figure 6-8). When stroke volume is severely affected by MR or systolic failure, reductions in aortic outflow velocities may be apparent.

• Quantitative methods include evaluation of the radius of color Doppler proximal flow convergence and the calculation of regurgitant fractions through volumetric flow analysis; however, these methods are time consuming and have not found widespread clinical application.

• The area of the color Doppler regurgitant jet relative to that of the receiving chamber is one means of semi-quantitatively evaluating the severity of valvular regurgitation; however, many physiologic and technical factors influence the size of the jet and this intuitively simple method has limitations. The width of the regurgitant jet at its origin is another, perhaps more accurate, means of evaluating the severity of regurgitation; a greater width indicates a larger orifice and, more severe regurgitation (Figures 6-12 and 6-13). The appearance of proximal flow convergence—the color Doppler appearance of acceleration through the regurgitant orifice—suggests that MR is at least of moderate severity (Figure 6-14).

• The density of the regurgitant continuous wave spectral Doppler signal is roughly proportional to the number of cells that move into the receiving chamber and is an alternative means of semi-quantitatively evaluating regurgitant severity (Figure 6-15).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree