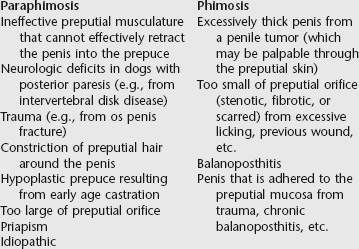

Chapter 224 The subject of disorders of the male external genitalia is too vast to cover thoroughly in this concise chapter. Neoplastic disorders of the male genitalia are discussed in Chapter 222 in this text. Therefore the focus of this chapter is on acquired conditions affecting the male external genitalia. Congenital disorders (e.g., cryptorchidism, persistent frenulum, hypospadias) are not included. The causes of paraphimosis are summarized in Box 224-1. The cranial preputial muscles normally draw the prepuce cranially about 1 cm in front of the tip of the penis. If the preputial musculature cannot retract effectively the penis into the prepuce because of muscular or neurologic deficits, then the prepuce may end at the tip of the penis or be shorter than the penis, allowing the tip of the penis to remain exposed continuously. About 30% of paraphimosis cases are idiopathic (Papazoglou, 2001). Like paraphimosis, phimosis can have a number of developmental or acquired causes. The acquired causes of phimosis are summarized in Box 224-1. If the penis will not stay within the prepuce after replacement, additional surgery is needed. These techniques include a purse-string suture at the preputial orifice, preputial orifice narrowing, preputial lengthening (preputioplasty), cranial preputial advancement, preputial muscle myorrhaphy, and phallopexy. Phallopexy is the author’s preferred method for penile retention, which is a technique of creating a permanent adhesion between the dorsal surface of the penis and the preputial mucosa (Somerville and Anderson, 2001). If the penis cannot be returned to the prepuce or if it has been severely damaged, a complete or subtotal penile amputation with concurrent urethrostomy should be performed (Pavletic and O’Bell, 2007). The prognosis is good to guarded for resolution of paraphimosis, depending on the severity and duration of clinical signs. The owner must be informed that erection and ejaculation in the animal may be impaired after paraphimosis. Common owner complaints for a patient with phimosis is that their pet may lick its prepuce excessively, may dribble urine from the preputial opening after urination, may suffer from an offensive or hemorrhagic preputial discharge, or may have a fluid-distended prepuce, stranguria, and pollakiuria. The diagnosis is often obvious once attempts are made to extend the penis for examination. In cases in which urine is voided into the preputial cavity, a secondary balanoposthitis may be evident as inflammation (reddening, swelling, and ulceration) of the tissues at the preputial opening. A bacterial culture and sensitivity must be submitted before treating balanoposthitis. Fluid (usually retained urine) may be palpable inside the preputial cavity; this also should be cultured. Other than direct examination, the diagnosis can be made using contrast radiography or ultrasonography. Contrast radiography is accomplished by filling the preputial cavity with saline and then taking radiographs of the penis and prepuce. Ultrasonographic examination largely can achieve the same results as contrast radiography. Ultrasonography allows for the detection of adhesions between the penis and preputial mucosa that were not detected by palpation through the preputial skin (Payan-Carreira and Bessa, 2008).

Acquired Nonneoplastic Disorders of the Male External Genitalia

Penis and Prepuce

Paraphimosis and Phimosis

Paraphimosis

Phimosis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Acquired Nonneoplastic Disorders of the Male External Genitalia

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue