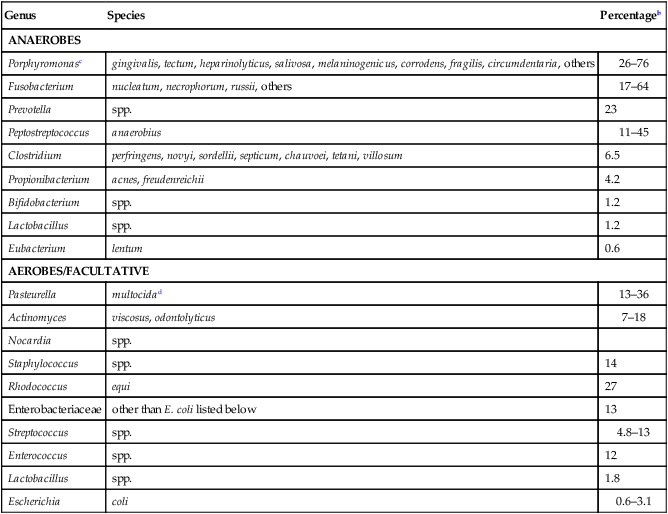

Abscesses, which are characterized by an accumulation of pus, can occur in almost any tissue (Table 50-1). Percutaneous abscesses are the most common bacterial infections of feline skin and probably the most common site of abscess formation in dogs and cats. The following discussion focuses on feline cutaneous abscesses, although the principles of diagnosis and treatment are similar in any location. See infections in the various system chapters (Chapters 84 to 92) for a discussion of abscesses in these locations. Abscesses develop more frequently in cats than they do in dogs, owing to the tough, elastic nature of feline skin, which readily seals over contaminated puncture wounds, causing the accumulation of subcutaneous exudates. Sharp teeth and fighting behavior, especially of adult males, are important predisposing factors to abscess formation. The size and degree of abscess formation also depend on many other factors, including the overlying skin tension, amount of dead space, and gravitation of exudate below the point of penetration. Pus-filled cavities that form above the puncture site drain easily. Cavities that gravitate below the puncture site become overdistended and may repeatedly drain through the puncture site without complete resolution. TABLE 50-1 Various Anatomic Locations of Canine and Feline Abscesses Because feline abscesses usually result from bites and scratches, the most common organisms found within them are resident oral microflora (Table 50-2).* Although more difficult to cultivate, anaerobes are more frequently isolated than are aerobes. The supposition that Pasteurella multocida is the most common organism involved in cat abscesses is incorrect if one considers the concurrent anaerobic bacterial isolation.87 Anaerobes can often be isolated in greater frequency. P. multocida is likely the most common facultative aerobic organism contaminating cat bite wounds (see Table 50-2). Cats that sustain bite injuries are more likely to become infected with feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) (see Chapter 12) or feline foamy virus (see Chapter 15). TABLE 50-2 Bacteria Isolated from Feline Abscessesa aSummarized from data in References 15, 16, 32, 34, 39, 46, 50, 53, 66–68, 76, 97, 101. bPercentage of the class of isolates (anaerobes or aerobes) cultured from feline abscesses. The clinical signs of abscess formation in cats reflect the site and severity of the infection. Abscesses are usually located around the cat’s legs, face, back, and base of the tail (Fig. 50-1). Some cats have a noticeable swelling with few other signs of illness, whereas more extensive infection is associated with fever (39.7° C to 40.6° C [103.6° F to 105.2° F]), anorexia, depression, and regional lymphadenomegaly. Pain is usually present at the site of infection, and obvious swelling or warmth may or may not occur. Mature abscesses that are ready to discharge are usually tender with a soft, fluctuant central area. Feline skin easily stretches over distended abscesses. Redness or discoloration is rarely apparent unless the blood vascular supply has been compromised. Drainage of white, creamy, purulent material occurs spontaneously or after surgical lancing. Foul-smelling, red-brown discharges occur, especially with tissue necrosis and virulent anaerobic bacterial infection. Systemic signs often abate once the abscess ruptures, and the only evidence of infection may be matted hair at the site of drainage. Careful examination in the area of swelling usually reveals a small puncture wound covered by a crust. Recurrent abscesses at the same site suggest underlying osteomyelitis or neoplasia, poor surgical drainage, immunodeficiency (e.g., feline leukemia virus [FeLV] or FIV infection), antimicrobial resistance, or the presence of a foreign body. Abscesses associated with foreign bodies, underlying osteomyelitis, or certain organisms such as Nocardia or Mycobacterium also tend to recur, persist, or spread in tissues (Fig. 50-2). Abscesses in dogs and cats are often associated with noticeable regional lymphadenomegaly. Sometimes the overlying skin may become necrotic, and exudate drains externally (Fig. 50-3). Determining the presence of an abscess is usually based on clinical history and examination. Abscesses should be expected in cats that develop an acute onset of unexplained fever, anorexia, or lameness, even in the absence of an obvious swelling, given that abscess formation may be delayed or hidden. The differential leukocyte count can help in determining the extent of infection and the animal’s ability to control it. A low count with an inappropriate shift is associated with diffuse infection or cellulitis. A mature neutrophilia is more characteristic of a walled-off or mature abscess. A nonregenerative (occasionally microcytic) anemia is present in accordance with chronic inflammation and iron sequestration.79 Severe leukopenia (a cell count of under 4000/mm3), with or without an associated anemia, may be present in cats infected with FeLV or FIV that develop chronic or recurrent abscesses as a result of immunosuppression. Unlike those in FeLV- or FIV-infected cats, the leukograms usually improve in immunocompetent cats after the abscesses drain. Because a high proportion of outdoor cats with cutaneous wounds have FIV infection,37 testing for this disease should be done at the time of initial examination, and at least 30 days thereafter, to determine if they became infected from the bite incident. Ultrasonography can be used to view the extent of a swelling and accumulation of fluid or pus in soft-tissue planes.1,6 Grass awns characteristically appear as double or triple spindle-shaped echogenic shadows within soft tissues.36a Minimally invasive ultrasound-guided retrieval of foreign material has also been helpful in avoiding standard surgical methods.88 Radiographic contrast procedures may be helpful in determining the extent or depth of a draining fistulous tract. Injection of contrast via an indwelling Foley catheter can be followed by radiography, computerized tomography scans, or magnetic resonance imaging. Cerebrospinal fluid evaluation and radiographic imaging is needed to detect central nervous system abscesses within the cranial vault or spinal canal.75

Abscesses and Botryomycosis Caused by Bacteria

Abscesses

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Location (Chapter)

Physical Causes

References

Subcutaneous (50, 51, 84)

Fight wounds, contaminated surgical wounds, underlying osteomyelitis, foreign material, glandular infections

14, 21, 27, 32, 76

Para-aural (84)

Pinna trauma or lacerations

29, 59

Retrobulbar, orbital (92)

Suppurative myositis, cellulitis, or abscess, foreign material

5a, 45, 58, 71, 78, 104, 109

Retropharyngeal (88)

Penetrating foreign material

8, 74

Lingual (88)

Foreign material, penetrating wound

55, 107

Dental (88)

Fractured tooth, periodontitis

105

Periesophageal (88)

Esophagoscopy complication

35

Pulmonary (87)

Aspiration, focal necrosis, hematogenous

48, 110

Pyothorax (87)

Inhaled foreign bodies, pneumonia, pulmonary abscess, penetrating wound

9, 33, 85, 96

Mediastinal (87)

Penetrating or inhaled foreign bodies

57, 91

Pericardial (86)

Bacterial translocation, penetrating foreign bodies

83

Myocardial (86)

Hematogenous, valvular endocarditis

60

Intra-abdominal (88)

Gut perforations, penetrating injuries, pancreatitis, foreign material

31, 94, 106

Hepatic (89)

Biliary infections or neoplasia, hematogenous-arterial or portal circulation

92, 95, 112

Pancreatic (88)

Pancreatitis, biliary infections, injuries

4, 51, 103

Splenic (88)

Hematogenous

36

Omental (88)

Vascular compromise, foreign material

25

Perirenal, renal (90)

Pyelonephritis, nephrolithiasis, trauma, hematogenous

2, 43, 47, 48, 62, 69, 113

Prostatic (90)

Urinary infection, intact males, urolithiasis, neoplasia

49, 54, 73, 86, 100

Uterine (90)

Incomplete removal ovariohysterectomy

24

Perineal (88)

Bowel perforation

70a

Mammary (90)

Pregnancy and lactation

21

Intracranial (91)

Bacteremia, otitis interna, retrobulbar abscess, penetrating wound

9, 17, 23, 56, 72, 91, 99

Paravertebral, epidural (85, 91)

Foreign bodies, penetrating wounds, diskospondylitis

11, 19, 28, 38, 44, 61, 75, 77, 81, 89

Fascial (33, 85)

Necrotizing fasciitis, usually gram-positive and anaerobic infections, foreign body migration

36a, 42, 84

Muscle (85)

Penetrating wound

13

Genus

Species

Percentageb

ANAEROBES

Porphyromonasc

gingivalis, tectum, heparinolyticus, salivosa, melaninogenicus, corrodens, fragilis, circumdentaria, others

26–76

Fusobacterium

nucleatum, necrophorum, russii, others

17–64

Prevotella

spp.

23

Peptostreptococcus

anaerobius

11–45

Clostridium

perfringens, novyi, sordellii, septicum, chauvoei, tetani, villosum

6.5

Propionibacterium

acnes, freudenreichii

4.2

Bifidobacterium

spp.

1.2

Lactobacillus

spp.

1.2

Eubacterium

lentum

0.6

AEROBES/FACULTATIVE

Pasteurella

multocidad

13–36

Actinomyces

viscosus, odontolyticus

7–18

Nocardia

spp.

Staphylococcus

spp.

14

Rhodococcus

equi

27

Enterobacteriaceae

other than E. coli listed below

13

Streptococcus

spp.

4.8–13

Enterococcus

spp.

12

Lactobacillus

spp.

1.8

Escherichia

coli

0.6–3.1

Clinical Findings

Diagnosis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Veterian Key

Fastest Veterinary Medicine Insight Engine