What role does surgery play in the treatment of cancer? This is variable, but virtually all cancer patients have some sort of surgical event, whether it is a biopsy to obtain the diagnosis or definitive surgical treatment. Some types of cancer can be cured with surgery; other times, palliation is the goal. A surgical oncologist must be adaptable. Sometimes a delicate, minimally disruptive surgery is prudent; at other times, more aggressive or extensive surgery would best suit the patient. It is important to administer the correct surgical dose (intralesional, marginal, wide or radical) to best fit the particular cancer patient and the availability and suitability of adjuvant treatments such as radiation therapy. The ability to modify surgical technique and surgical expectations to suit the individual case is a unique and valuable skill. Consider how differently the cancer surgeon must approach solid tumours of the skin and subcutaneous tissues, bowel obstruction due to mesenteric lymph node enlargement, intranasal tumours, solid tumours of the anal sac and lymphoma.

The goal of this chapter is to explain the concepts of surgical oncology; however, ‘cancer does what cancer wants’, and broad generalizations are difficult. A thinking surgeon is required, preferably working in conjunction with a medical oncologist, a radiation oncologist, a radiologist, a pathologist and so on, so that the animal as a whole is considered, not just its tumour (see

Chapter 3). The following sections in this chapter deal with important points to convey the concepts of surgical oncology.

What am I treating?

Let us start with a diagnosis. It is important to point out that diagnostic imaging and physical examination can provide valuable information, but are never going to give a definitive diagnosis of the exact tumour type. Extracting cells from the patient (cytology or histopathology) to ascertain the type of cancer being treated prior to the actual definitive treatment is very important. Further work-up, treatment type (e.g. chemotherapy, radiation therapy, marginal versus wide surgical resection) and prognosis can change markedly with an accurate diagnosis. For example, a subcutaneous lipoma can look and feel exactly the same as a mast cell tumour. By way of another example, assumptions that liver masses seen on ultrasound are neoplastic or benign cannot be accurate; you cannot be sure until you have some tissue or cells for examination. Guesswork is, by definition, uncertain and should not be used to condemn a patient to a poor prognosis, or to wrongly assume a good prognosis. Remember, a lump is a lump until it has been sampled!

However, in certain cases a preoperative biopsy is an unnecessary or risky step and is not indicated.

When to biopsy?

When the result of the biopsy would change the way you would treat (e.g. chemotherapy if the mediastinal mass is a lymphoma or surgery if it is thymoma), then a biopsy is indicated. Conversely, if treatment would not change – for example, lung lobectomy for a solitary lung mass (granuloma or primary lung tumour) or splenectomy for a localized bleeding splenic mass (benign or malignant), or if the biopsy is as difficult or dangerous as the curative treatment (e.g. spinal cord biopsy), then the biopsy information should be obtained after surgical removal (

Ehrhart & Withrow 2007).

Another consideration for acquiring a preoperative biopsy is in the situation where the client’s willingness to treat would depend on the tumour type and the attending prognosis (

Ehrhart & Withrow 2007). For instance, a client may be willing to perform a mandibulectomy for oral squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) but not for amelanotic melanoma. A large melanoma carries a far worse prognosis than a rostrally located SCC and both can look the same grossly. Only a biopsy can differentiate them accurately, so in this case a preoperative biopsy is indicated.

What am I treating?

Cytology: fine needle aspirate (FNA) cytology

This is a great place to start on the hunt for a diagnosis. Cytology is not equivalent to histopathology, so it is not a ‘biopsy’, but a very good first line at gaining cellular material for a diagnosis. For externally accessible masses this is an easy, cost-effective, low-risk technique and very important information is often obtained (see

Chapter 6). Ensure all skin or subcutaneous lumps undergo FNA!

Biopsy methods

The three tenets of oncology are Biopsy! Biopsy! Biopsy! This is the most important point of this chapter. There are a number of biopsy techniques to consider and the selection depends on the particular clinical setting and operator skill and preference (

Table 5.1).

Table 5.1 Some examples of indications for incisional versus excisional biopsy

Tumour type |

Biopsy type |

|---|

Intranasal |

Incisional (usually) |

Solitary liver mass |

Excisional, with wide margin if possible |

Diffuse liver masses |

Incisional |

Solitary lung mass |

Excisional, with wide margin if possible |

Solitary gastrointestinal |

Excisional, with wide (5–6 cm) margin if possible |

Multiple gastrointestinal |

Incisional |

Localized splenic mass(es) |

Excisional |

Needle core/‘tru-cut’ biopsy

This is a minimally invasive method of obtaining tissue, and is an example of an incisional biopsy. It can be done under sedation on an outpatient basis. Usually three samples are taken. The problem is that only small tissue samples are obtained, and if there is friable, very vascular or necrotic tissue, this can hinder the pathologist’s diagnosis (e.g. haemangiosarcomas, oral masses). If only small bits of tissue are obtained, it may be better to try an incisional (wedge) biopsy. Tru-cut biopsies can be used for external or internal lesions (e.g. ultrasound-guided liver, spleen, kidney, prostate, mediastinal mass, etc.). A Jam-shidi bone biopsy punch is a similar concept used to biopsy bony lesions (but must be done under general anaesthesia). It is important to use any punch or needle device correctly and accurately to ensure you deliver to the pathologist a representative tissue sample for histopathology.

Punch biopsy

This is a short and wide biopsy (as opposed to the long thin sample retrieved by needle devices) and can be used on any external tumour (oral, perianal, skin). A short general anaesthetic is usually required. Some also use this technique for liver biopsy at the time of open surgery.

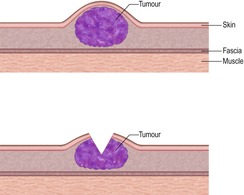

This also typically involves a general anaesthetic and a minor surgery. For large, ulcerated, external masses where innervated host tissue does not need to be penetrated (tumours do not have nociceptors), a biopsy may be obtained without sedation or anaesthesia. Generally, the skin is cleaned and prepared aseptically and a scalpel blade is used to incise the skin and underlying tumour to remove a wedge of tissue. Incisional biopsy is employed if the surgeon has any doubt about compromising the definitive surgery with a larger (excisional) biopsy (

Figure 5.2 and

Figure 5.3).