The spleen performs a number of functions in the body, one of which is as a secondary organ of haematopoiesis. This function usually ceases at birth but in dogs a limited capacity remains and is known as extramedullary haematopoiesis. It is seen in adult animals with extra demand, due either to infiltrative disease of the marrow or spleen or excessive destruction of erythrocytes. The spleen has a reservoir capacity and can store between 10 and 20% of the total blood volume of the dog. It is also a major filtration organ and is the principal site of IgM production in both the dog and cat. A number of tumours can arise from the spleen or infiltrate it.

Tumours affecting the spleen can do so by infiltrating the organ throughout, causing generalized splenomegaly or discrete masses. Tumours of myeloproliferative origin, lymphoma (LSA), mast cell tumour (MCT) and histiocytic disorders are the most commonly occurring tumours to cause diffuse enlargement of the spleen. Inflammatory disease, splenitis or extramedullary haematopoiesis in the dog are the most common non-neoplastic conditions that cause diffuse splenomegaly. In cats the most common splenic tumours are LSA and MCT.

Tumours that arise from the mesenchymal elements of the spleen typically give rise to isolated splenic masses; however, some tumours such as MCT or LSA can do both. Non-neoplastic splenic masses are more common than neoplastic ones but it can be difficult to distinguish between them without surgery. The most common malignant tumour of the spleen in dogs is haemangiosarcoma (HSA); other malignant tumours include leiomyosarcoma, fibrosarcoma (FSA), histiocytic sarcoma (HS), liposarcoma and osteosarcoma (OSA); benign tumours include haemangioma, fibroma, leiomyoma and myolipoma; other splenic disease that may appear neoplastic includes nodular hyperplasia, haematoma and abscess. Fibrohistiocytic nodules comprise both the benign elements of nodular hyperplasia and the more malignant characteristics of a sarcoma (Spangler & Kass 1998).

Clinical signs of splenic neoplasia

Patients with splenic disease can present with a number of clinical signs depending on the underlying cause. These can include anorexia, vomiting, polyuria/polydipsia (PU/PD), acute abdominal pain, weakness, pale mucous membranes, collapse or in some cases the client has noticed abdominal swelling.

Diagnostic work-up

Presenting clinical signs, followed by a thorough physical examination, will guide the rest of the diagnostic evaluation. Careful abdominal palpation will often reveal the presence of an enlarged spleen, mid-abdominal mass effect or ascites. Abdominal radiographs can be helpful in the absence of any fluid. Routine haematology may show anaemia sufficient to indicate haemorrhage or elevated white blood cell count, which may be either a mature neutrophilia (seen in patients with HSA or splenic torsion) or abnormal lymphoid/myeloid cells (leukaemia). Coagulation profiles and platelet counts should be checked because of the high incidence of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) in patients with splenic disease.

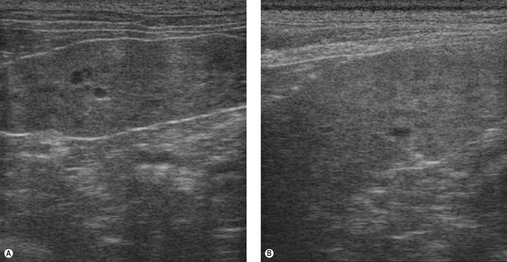

Abdominal ultrasound provides valuable information as to the size, location and echogenicity of masses within the spleen. It also provides information in the case of generalized splenomegaly because infiltrative disease will often give a ‘Swiss cheese’ effect to the parenchyma. Fine needle aspirates (FNA) or tru-cut biopsies of the spleen can be taken and are particularly helpful in diagnosing LSA, leukaemia and MCT (Figure 23.1A) and in ruling out non-neoplastic conditions such as splenitis (Figure 23.1B).

The risk/benefit of biopsying a splenic mass is debatable and depends on the overall appearance of the spleen: a large solitary bleeding mass requires surgery; multiple nodules (nodular hyperplasia or fibrohistiocytic nodules) may be biopsied by ultrasound guidance; diffuse infiltrative disease can be diagnosed on FNA. The entire abdominal cavity should be examined with ultrasound prior to surgery, if possible. In some cases the tumour can be so large that other organs cannot be visualized easily, or the amount of fluid makes complete examination difficult. However, ultrasound findings should not be over-interpreted, e.g. nodular changes in the liver cannot be definitively diagnosed as metastasis on the basis of image alone.

Thoracic radiographs should be taken before any surgery.

Treatment

The treatment of choice for splenic masses is splenectomy. It is important to remember that up to 50% of splenic masses are benign or low grade and have a good prognosis with successful surgery.

Biopsies should be taken of liver (even if grossly normal) and any other abdominal pathology, if feasible. More than one dog has had ectopic splenic nodules, not metastatic HSA. Bleeding liver mass(es) may also be removed if possible, to control haemorrhage.

Animals with splenic masses may experience complications of surgery and anaesthesia because of anaemia, thrombocytopenia, hypoproteinaemia, DIC, hypovolaemia, hypotension, hypoxaemia, cardiac arrhythmias and uncontrollable haemorrhage. In cases with considerable, rapid blood loss into the abdominal cavity, a pressure bandage applied to the abdomen may help stem bleeding while the patient is made stable enough for surgery via intravascular fluid volume replacement, oxygen support, blood products, colloids and the like. Use pressor support with dopamine, dobutamine is also useful; atropine and adrenaline are also kept on hand.

The surgery to stop the bleeding (i.e. splenectomy) should not be delayed unnecessarily, but also not performed if the patient is thought to benefit from further short-term stabilization. In the postoperative period, blood products may still be needed (Chapter 9), but for any patient in DIC removal of the tumour should result in rapid normalization of clotting times. A continuous ECG is required to monitor for cardiac arrhythmias; this is a common occurrence post splenectomy and may not occur until 48 hours after surgery. Intervention to correct the arrhythmia is dependent on its severity and if the patient is showing clinical signs. Lidocaine infusions should be used if required and then switched to oral mexiletine for a few days.

CANINE TUMOURS

Splenic haemangiosarcoma (HSA)

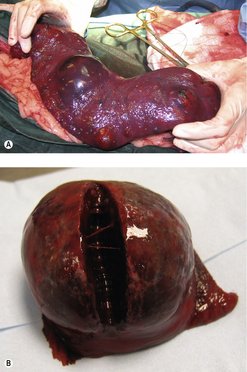

Splenic HSA is the most common canine neoplasm of the spleen and the most common presentation of HSA in the dog. In one study of 500 cases of splenomegaly, the ratio of benign to malignant disease was about 50 : 50, and HSA made up 51% of splenic malignancies (Spangler & Kass 1997). Another study showed that of 100 cases of splenomegaly in dogs, two-thirds had malignant disease, and two-thirds of those malignancies were HSA (Johnson et al 1989). In another study of 87 cases of splenic abnormality, about 50% were neoplastic, and 44% of these were HSA (Day et al 1995). It is typically seen in older dogs with a median age of 9 years, although young dogs may be affected. Breed predispositions include German Shepherds, Golden Retrievers and Labrador Retrievers (Brown et al 1985, Day et al 1995) (Figure 23.2).

|

| Figure 23.2 |

In another study of over 1500 cases, splenic haematoma and hyperplastic nodules made up the bulk of splenic lesions, but HSA was the most frequent neoplasm. Splenic haematoma and HSA were grossly indistinguishable in most cases (Spangler & Culbertson 1992).

HSA is highly metastatic and spreads haematogenously. The primary metastatic site is the liver, but up to 25% of dogs with splenic HSA have tumour in the right atrium (Waters et al 1988). Direct seeding of tumour through the omentum and mesentery can occur when these tumours bleed or rupture. Other metastatic sites include the lung, skin and brain.

Clinical signs

Clinical signs are typically associated with blood loss, either generalized weakness or acute collapse; however, some patients will present for lethargy without obvious signs of haemorrhage. If the bleed has been severe due to splenic rupture, the patient may present with very pale mucous membranes and in haemorrhagic shock. A packed cell volume (PCV) will quickly show the degree of anaemia.

Diagnostic work up

• Haematology: leucocytosis is common with HSA, anaemia can be due either to acute blood loss or secondary to destruction of red cells passing through the abnormal blood vessels of the tumour (microangiopathic).

• Abdominal radiographs: the mass can be small or obscured by fluid.

• Abdominal ultrasound: a complex hypoechoic mass is characteristic of HSA and the presence of blood-filled cavernous spaces means presurgical biopsy is unlikely to be rewarding and may cause significant haemorrhage. It is important to evaluate the liver to rule out potential metastases. The major differentials that will appear to be very similar to HSA on ultrasound are haemangioma and haematoma, and in all instances the treatment of choice is splenectomy.

• Abdominocentesis: this is indicated in the presence of an effusion, and if it is ‘bloody’ in appearance, then the PCV should be taken and compared with the peripheral blood PCV (Figure 23.3).

|

| Figure 23.3 |

• Thoracic radiographs/CT: required to rule out metastatic disease that could make surgery contraindicated.

• Coagulation profile: this should be obtained prior to surgery; however, if this is not possible then an activated clotting time and buccal mucosal bleeding time are helpful.

Staging

Staging is important (see Table 23.1).

| Stage | Extent of disease |

|---|---|

| I | Confined to spleen |

| II | Ruptured spleen, no evidence of metastases |

| III | Ruptured spleen and metastases |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree