Blood types are genetic markers on erythrocyte surfaces that are antigenic and species specific. A set of blood types of two or more alleles makes up a blood group system. Dogs have more than a dozen blood group systems known as dog erythrocyte antigens (DEA); however, there is no DEA 2 blood group. Canine erythrocytes are either positive or negative for a blood type (e.g., DEA 4 positive or negative), and these blood types are thought to be inherited codominantly. In the DEA 1 system, which represents an exception, DEA 1.1 (A1) and 1.2 (A2) are apparently allelic and there even may be a DEA 1.3 (A3). Thus a dog can be DEA 1.1 positive or negative and DEA 1.1–negative dogs can be DEA 1.2 positive or negative. Recent studies by the author’s laboratory indicate that the DEA 1 blood group may be a continuum from negative, weak, moderate, to strongly positive rather than having two or three blood types.

The clinically most important canine blood type is DEA 1.1. DEA 1.1 (A1) elicits a strong alloantibody response after sensitization of a DEA 1.1–negative dog by a transfusion and thus can be responsible for a transfusion reaction in a DEA 1.1–negative dog previously transfused with DEA 1.1–positive blood. Transfusion reactions against other blood types rarely have been described. They include reactions against the DEA 4, Dal, and another common red cell antigen, and other clinically important blood types may be found in the future. No reagents currently are available against many antigens, and additional blood types continue to be recognized.

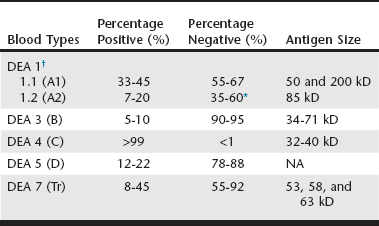

Only limited surveys on the frequency of these blood types have been reported (Web Table 26-1), which suggest possible geographic and breed-associated differences. For instance, all typed Saint Bernard and most golden retriever dogs tested are apparently DEA 1.1 positive. Some of the blood types are seen rarely (DEA 3), whereas others occur commonly (DEA 4). In Japan additional blood group systems have been proposed, but their associations to the DEA systems and their clinical importance have not been documented. Recently, an apparently new common red cell antigen has been identified that seems to be missing in some dalmatians; therefore it is named Dal red cell antigen.

Strongly antigenic blood types are of great clinical importance because they can elicit a potent alloantibody response. These alloantibodies may be of the immunoglobulin G (IgG) or IgM class and may be hemagglutinins or hemolysins. Based upon experimental and clinical data, dogs can become sensitized after receiving a mismatched transfusion (i.e., a blood unit positive for one or more blood types not found on the recipient’s red blood cells) but not by pregnancy.

There are no clinically important, naturally occurring alloantibodies (also known as isoantibodies) present before sensitization of a dog with a transfusion. Sensitizing dogs in experimental studies in the 1950s led to the documentation of some transfusion reactions caused by blood group incompatibilities and to the characterization of new blood types. Clinically the most antigenic blood type in dogs is the DEA 1.1. Transfusion of DEA 1.1–positive cells to a DEA 1.1–negative dog invariably elicits a strong alloantibody response. After a first transfusion, anti-DEA 1.1 antibodies develop after more than 4 days and may cause a delayed transfusion reaction. However, a previously sensitized DEA 1.1–negative dog can develop an acute hemolytic reaction after transfusion of DEA 1.1–positive blood. Transfusion reactions also may occur after a sensitized dog receives blood that is mismatched for a red blood cell antigen other than DEA 1.1. For instance, a whippet developed an alloantibody against a common red blood cell antigen, resulting in a general incompatibility with any donor except a littermate. Similarly, a dog with DEA 4–negative blood, another common antigen, showed an acute hemolytic transfusion reaction after receiving a second DEA 4–positive blood transfusion. However, in most cases the incompatible blood type has not been determined. Because administration of a small (<1 ml) amount of incompatible blood can result in life-threatening reactions the practice of giving small “test volumes” of donor blood to assess blood-type compatibilities is unacceptable. In contrast, pregnancy does not cause sensitization because of a complete placenta in dogs and does not induce alloantibody production; thus dogs with prior pregnancies can be used safely as donors.