Chapter 40 Zoonotic Diseases

Bacterial Diseases

Bordetella bronchiseptica is a gram-negative rod to which high morbidity and mortality rates in guinea pigs have been attributed (Fig. 40-1).3 Hamsters and mice do not appear to be as sensitive to this pathogen as other rodents.52 Bordetella bronchiseptica can be isolated from clinically normal rodents and lagomorphs. Clinical signs in affected rodents and lagomorphs are generally associated with the respiratory system and are characterized by nasal and ocular discharge, coughing, sneezing, and pneumonia. This pathogen has been associated with respiratory tract infections in humans. Although rodents and lagomorphs pose minimal risk in the dissemination of this bacterium to humans, at-risk individuals should take specific precautions to reduce exposure. Pet dogs are a greater risk to humans than nontraditional mammals for B. bronchispetica through increased mouth-to-face contact.

Fig. 40-1 Congested lungs removed from a guinea pig that died from infection with Bordetella bronchiseptica.

(Courtesy of Bruce Williams, DVM.)

Campylobacteriosis is a serious zoonotic disease responsible for the annual expenditure of millions of dollars in medical expenses. Although contaminated food (e.g., poultry) and water are the primary methods of exposure to Campylobacter species in the United States, infected pets (e.g., dogs, cats, horses, hamsters) may also be a source of this pathogenic bacterium.39 A very small percentage of the nearly 2 million confirmed cases a year of campylobacteriosis in the United States are attributed to pet exposure.39 While nontraditional small mammals may harbor Campylobacter jejuni or C. pylori, of the risk that they will transmit this organism to their owners is low. A pet animal with diarrhea is considered a risk factor for shedding of Campylobacter species, which resulted in 6.3% of the cases of campylobacteriosis reported in a 1993 study.44 Incubation of Campylobacter species is approximately 2 to 5 days, and the disease is generally self-limiting (10-14 days) in the immunocompetent host.19 Ferrets that have recovered from campylobacteriosis may shed the bacteria for more than 140 days.19 A 9-month bacteriologic survey of biomedical research ferrets suggests that ferrets may pose a special threat to individuals working with ferret colonies. In this study, C. jejuni and C. coli were isolated from 18% of the ferrets being tested.19 Although no cases of ferret-associated campylobacteriosis have been reported, the prevalence of Campylobacter species in these ferrets suggests that they may serve as a source of infection. When infected, humans usually suffer from a mild, self-limiting gastroenteritis, but the disease may develop into a generalized septicemia that can result in death.

Francisella tularensis is the causative agent of rabbit fever, or tularemia. This gram-negative coccobacillus is primarily a pathogen of wild rodents and lagomorphs. Captive rodents and lagomorphs generally are not considered important reservoirs for this microbe. The domestic cat is actually more likely to serve as a reservoir than other domestic species because of possible contact with infected wildlife (Fig. 40-2). Francisella tularensis can be transmitted by aerosolization, direct contact, or ectoparasites (fleas and ticks). Affected individuals may develop cutaneous lesions, respiratory disease, or meningitis.

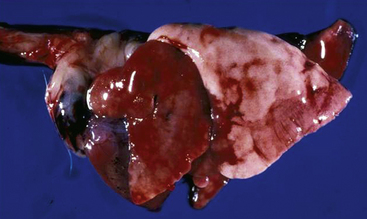

Fig. 40-2 Spleen and internal organs of beaver that died from infection with Franciella tularensis.

(Courtesy of Bruce Williams, DVM.)

Leptospira interrogans is frequently isolated from wild rodents. Individuals working with wild rodents or in areas where high densities of wild rodents are concentrated may be at risk of contracting leptospirosis. Leptospira interrogans, L. grippotyphosa, and L. icterohaemorrhagiae have been isolated from ferrets. Individuals who have contact with ferrets used for hunting may also be predisposed to leptospirosis. The bacteria are shed in the urine, and transmission may occur from direct contact or aerosolization of urine-contaminated food, water, bedding, or soil. Affected individuals may have chills, fever, and malaise or septicemia and generalized organ dysfunction. Although nontraditional small mammals kept as pets are not generally considered to be a source of L. interrogans for humans, these animals can serve as reservoirs for the spirochete, and appropriate precautions should be taken to prevent exposure. The incubation period for a human exposed to Leptospira organisms until infection occurs is 2 days to 4 weeks.6 The first signs associated with a human infection are a sudden fever, chills, headaches, vomiting, myalgia, and/or diarrhea.6 The human patient may recover from the initial disease condition and have no other problems from the infection. If more severe disease problems develop after the initial recovery, this is also called Weil’s disease (i.e., the development of kidney or liver failure or meningitis).

Pasteurella multocida, a gram-negative rod, is an opportunistic pathogen of lagomorphs and rodents. In rabbits, P. multocida can cause multisystemic disease and is difficult to eradicate. Because this organism is ubiquitous in the environment, inoculation into bite injuries or scratches received from lagomorphs or rodents can occur. In humans, P. multocida has also been associated with multisystemic disease. Susceptible individuals, including young children and immunocompromised adults, should practice strict hygiene after handling these animals. Bite or scratch injuries should be immediately disinfected and a physician contacted for additional information for wound management.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a gram-negative bacterium, is ubiquitous in the environment. While many exotic small animals are considered to be commensal hosts, few studies have characterized the prevalence of this opportunistic pathogen. A 2010 study in chinchillas reported the prevalence of P. aeruginosa to be nearly 42% in animals maintained as pets or in the laboratory setting.27 The P. aeruginosa isolated from chinchillas showed patterns of resistance to antibiotics commonly used to treat these animals in captivity. Because this organism is a common cause of nosocomial infections in humans, routine disinfection methods should be practiced after handling or cleaning small mammals and their cages to minimize the potential of exposure to this organism.

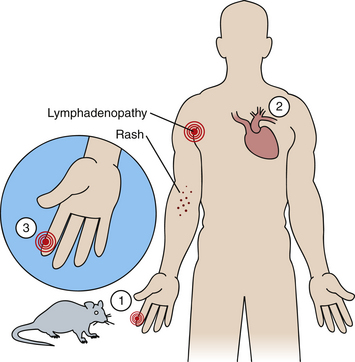

Rat-bite fever (RBF) is a rare but serious zoonosis caused by Streptobacillus moniliformis and Spirillum minus (Fig. 40-3). These gram-positive microbes are considered indigenous flora in rats and may be isolated from the nasal and oropharyngeal areas of these animals.40 Laboratory and pet rats are considered the primary reservoir for RBF, although wild rats and mice may also serve as competent reservoirs. These bacteria are primarily transmitted from a bite. The incubation for streptobacillary RBF in humans is approximately 3 to 10 days, whereas it is 1 to 6 days for spirillary RBF. The clinical signs attributed to RBF are generally observed at approximately the same time the bite wound is healing; they include relapsing fever, chills, vomiting, myalgia, and regional lymphadenopathy. Individuals infected with S. moniliformis frequently have a maculopapular rash on their extremities. This rash does not occur with spirillary RBF. In 2003, two cases were reported of previously healthy adult women dying from S. moniliformis septicemia 2 to 3 days after the initial onset of disease symptoms (e.g., headache, diarrhea, lethargy, myalgia, lymphadenopathy).23 In another case reported in 2004, a 24-year-old male pet shop employee died after becoming infected through a superficial skin wound that occurred from contact with a contaminated rat cage.47 Clinical signs were similar to those described for the women in the earlier report, although endocarditis and multiorgan failure ultimately led to the demise of the male patient. Rat-bite wounds should be immediately disinfected to reduce the likelihood of transmitting these pathogens, and care should be taken in working around enclosures with positive animals. Affected individuals should seek medical attention and report their exposure history.40 Physicians should be informed of a patient’s exposure to a rat if an owner is being examined for an unexplained febrile illness or sepsis.23,47 Although the disease is called rat-bite fever, approximately 30% of the patients confirmed with RBF have not reported being bitten or scratched by a rat.23,47 Wearing gloves, handwashing after handling a rat, and avoiding hand-to-mouth contact with the animal or when cleaning its cage will help reduce the risk of being infected with RBF or other potential rodent-transmitted zoonotic infections.40

Salmonella species, which are gram-negative facultative anaerobes, are ubiquitous in the environment. This microbe has been associated with both enzootic and epizootic outbreaks in captive rodent and lagomorph colonies.14,24,38,48 Salmonella have also been isolated from other nontraditional small mammals, including sugar gliders, African hedgehogs, and ferrets.52 All vertebrate species should be considered susceptible to salmonella infection. There are more than 2,400 different Salmonella serotypes and all are potentially pathogenic, although most infections in humans and animals are caused by less than 12 serotypes. Salmonella enterica ser. Enteritidis (S. enteritidis) and S. enterica ser. Typhimurium are the two most common serotypes isolated from rodents and lagomorphs, whereas S. enterica ser. Tilene appears to be the most common serotype isolated from sugar gliders and hedgehogs.26,53 S. enterica serovars Typhimurium, Hadar, Kentucky, and Enteritidis have been isolated from ferrets.26,53 Most rodents and ferrets appear to be asymptomatic reservoirs for this microbe. One exception is the guinea pig, which can develop life-threatening septicemia. Salmonella infections are primarily transmitted by the fecal-oral route or from contaminated fomites, but they can also can be transmitted by aerosol through the conjunctiva in some species.35 Affected vertebrates may have anorexia, weight loss, enteritis, lymphadenopathy, or septicemia. Reproductive disorders, including abortions and premature birth, have also been associated with Salmonella infections in rodents and lagomorphs. Humans who contract salmonellosis from these animals may have headaches, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, enteritis, or septicemia.50 The incubation period in humans is approximately 6 to 48 hours. Humans can acquire Salmonella from either direct or indirect exposure to mammal reservoirs. In 1994, a case of hedgehog-associated salmonellosis in a 10-month-old girl from Washington was attributed to indirect contact with the family’s breeding colony of hedgehogs.30 From December 2003 through October 2004, there were 28 reported cases in the United States of multi-drug-resistant S. enterica ser. Typhimurium matched by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis to isolates from rodents (e.g., hamsters, mice) purchased at retail pet stores.49 The median age of those affected was 16, and a large number of affected individuals (40%) were hospitalized. In addition to having been isolated from humans and rodents, the organism was also found in rodent cages and transport boxes. Veterinarians should remind clients to be aware of these risks when they are cleaning their pet rodents and cages. Frozen rodents intended as food for reptiles have also been found to serve as a potential zoonotic source of S. enterica ser. Typhimurium.21 Because of the inherent zoonotic risks associated with the ownership of these and other pets, pet ownership should always involve adult supervision. Strict hygiene, including handwashing with soap, should be practiced to reduce the risk of exposure. The recommendations for reducing the risk of reptile-associated salmonellosis formulated by the Association of Reptile and Amphibian Veterinarians and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention would also be appropriate to distribute to owners of nontraditional small mammals.4

There have been three known major historic pandemics of plague. Yersinia pestis, the causative agent of plague, is generally transmitted by flea-borne vectors, although it can also be spread by contaminated respiratory secretions with the pneumonic form and direct contact with infected tissues or fluids from handling sick or dead animals. The three forms of disease associated with Y. pestis infection in humans are (1) bubonic plague (enlarged sensitive lymph nodes, fever, chills), (2) septicemic plague (fever, chills, prostration, shock, and bleeding into the skin and other organs), (3) pneumonic plague (fever, chills, cough and difficulty breathing, rapid shock and death if not treated early).7 The primary vector for Y. pestis is the rodent flea (Xenopsylla cheopis), although Thrasis, Diamanus, Hoplopsyllus, and Odropsylla species and Orchopeas sexentatus are also competent vectors. In the United States, Y. pestis is primarily a problem in southwestern states (e.g., New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, California) and may be spread by domestic species. Because captive nontraditional pet mammals (e.g., chipmunks, prairie dogs) can also serve as competent hosts for many of the vectors reported for this pathogen, precautions should be taken to prevent the introduction of flea vectors into the home. Although there are no reported cases of plague associated with nontraditional pets in the United States, guinea pigs have been associated with plague in Andean countries, where they are raised for food.42

Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and Y. enterocolitica, opportunistic gram-negative coccobacilli, are routinely isolated from clinically normal rodents and lagomorphs. Y. pseudotuberculosis has been associated with epizootics in guinea pig colonies worldwide, in rats from Japan, and in hares from Europe.2 Affected animals generally suffer from weight loss and enteritis. Mortality rates can approach 75%. Wild rodents are considered to play an important role in the transmission of this pathogen. Although captive rodents have not been identified as an important source of infection in humans, they certainly could serve as competent reservoirs of the bacteria in the human environment.

Yersinia enterocolitica has been associated with epizootics in chinchillas from Europe, Mexico, and the United States.2 Septicemia was a common finding, and affected animals had enteritis and weight loss. Studies evaluating the prevalence of enterocolitic yersiniosis in wild rodent populations from the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Scandinavia, and Chile suggest that the prevalence of this pathogen in wild rodents is low (4%-26%). Although pathologic lesions, including abscesses of the liver and intestinal lesions, have been reported in wild rodents, most such animals screened for this pathogen are negative. The biotypes characterized in rodents are not the same as those that infect humans. Although rodents are not considered an important source of enterocolitic yersiniosis in humans, veterinarians and animal caretakers should practice strict hygiene and take appropriate precautions in working with infected rodents and lagomorphs.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree