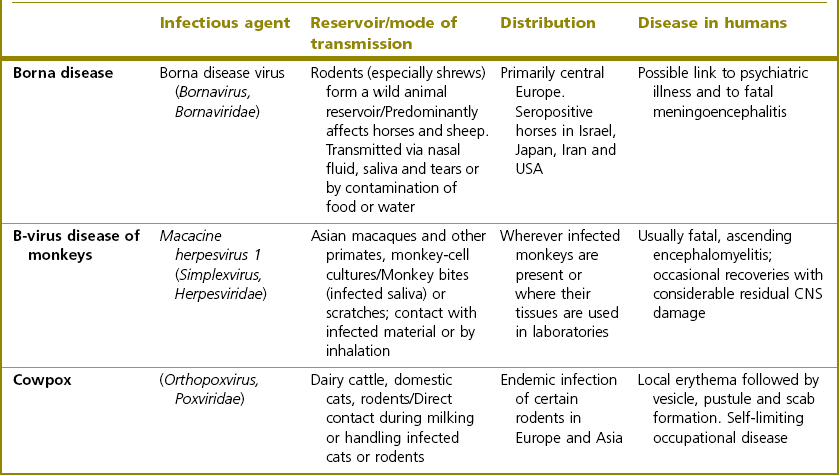

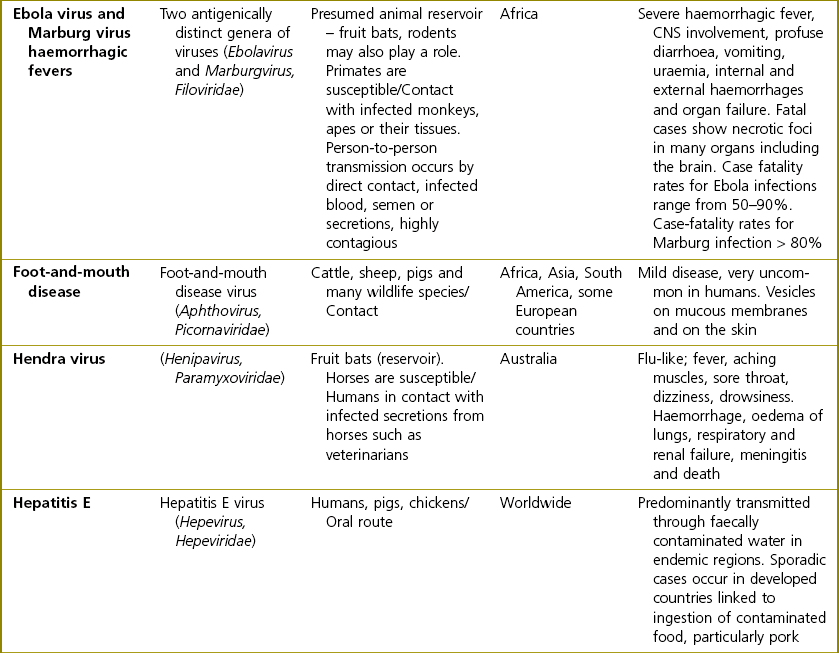

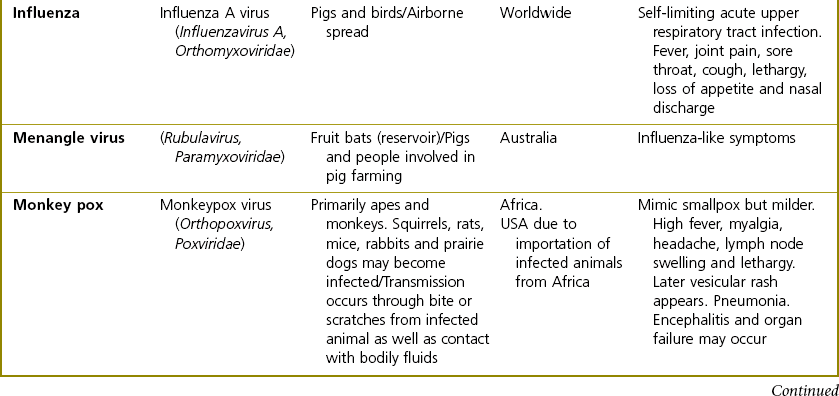

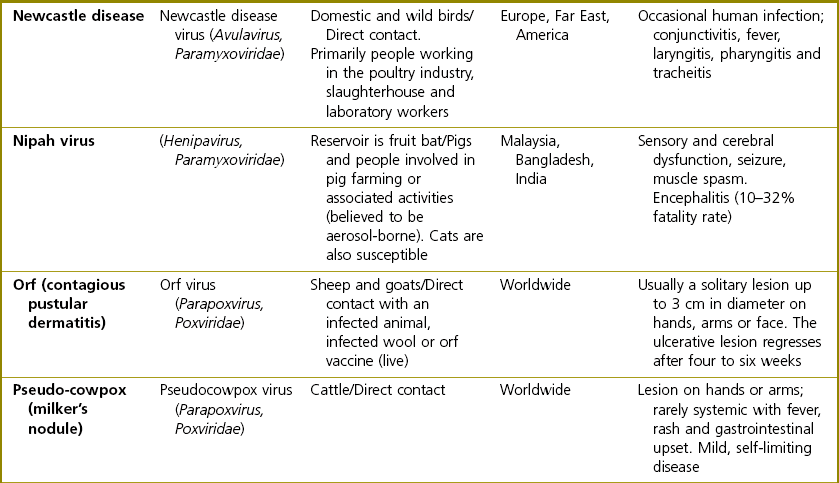

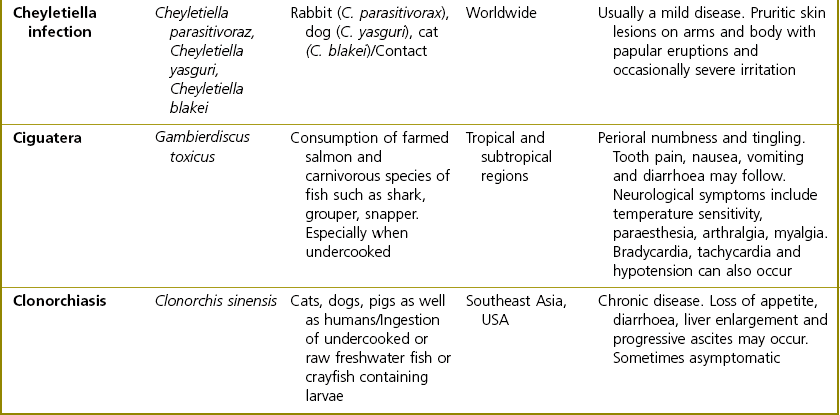

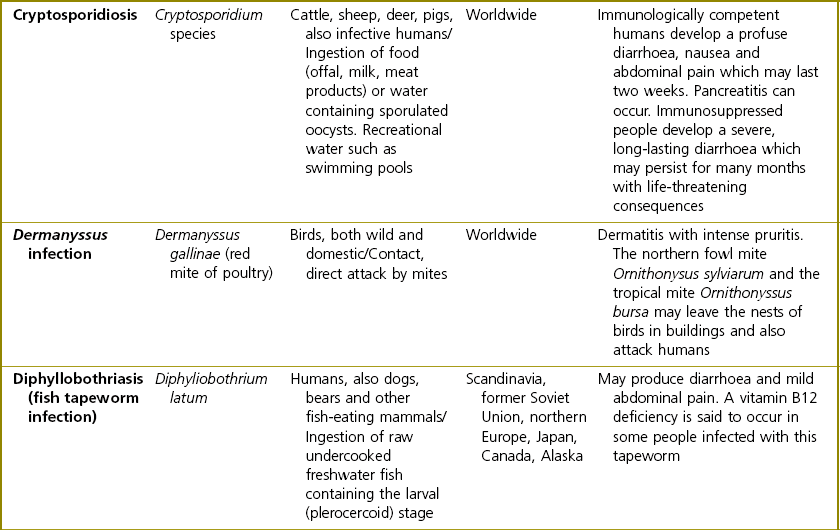

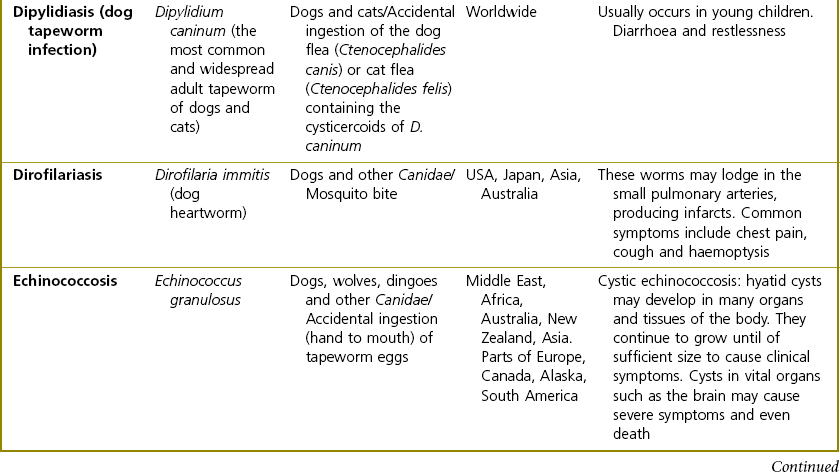

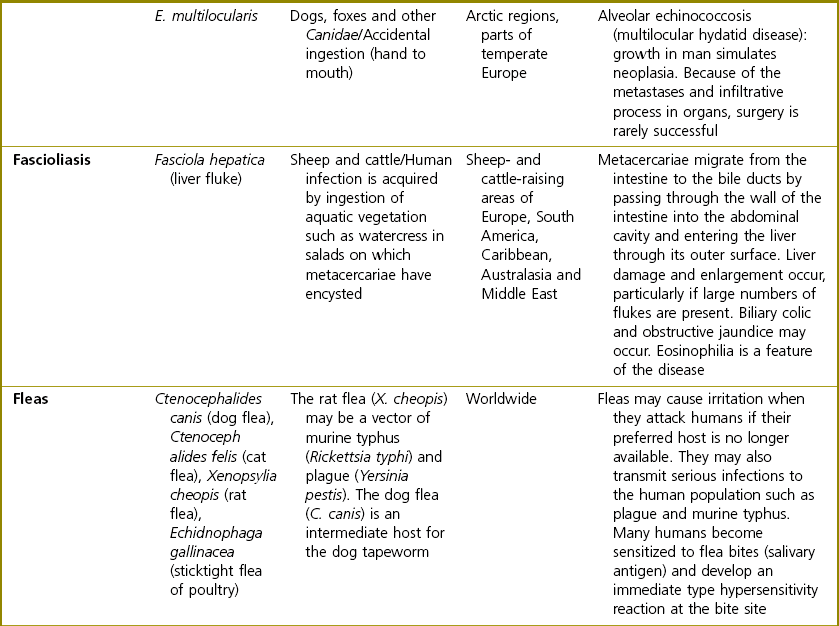

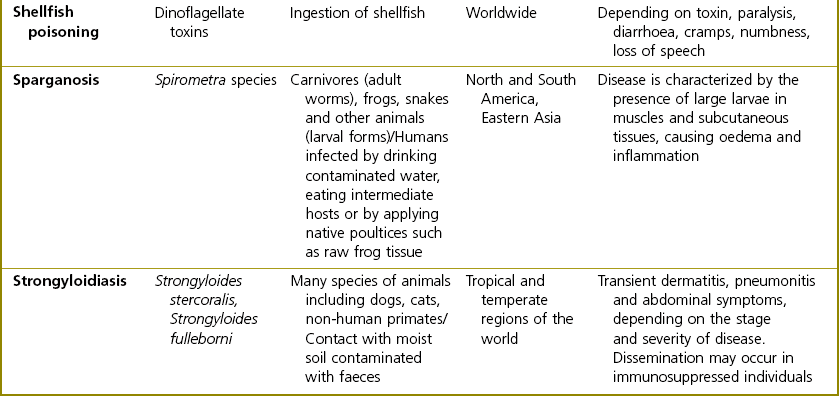

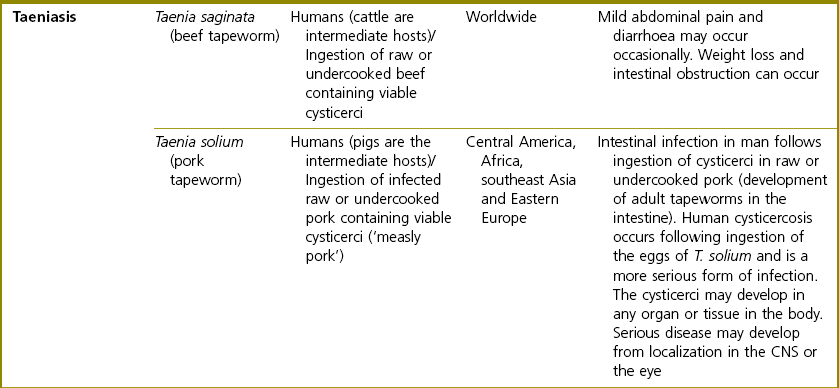

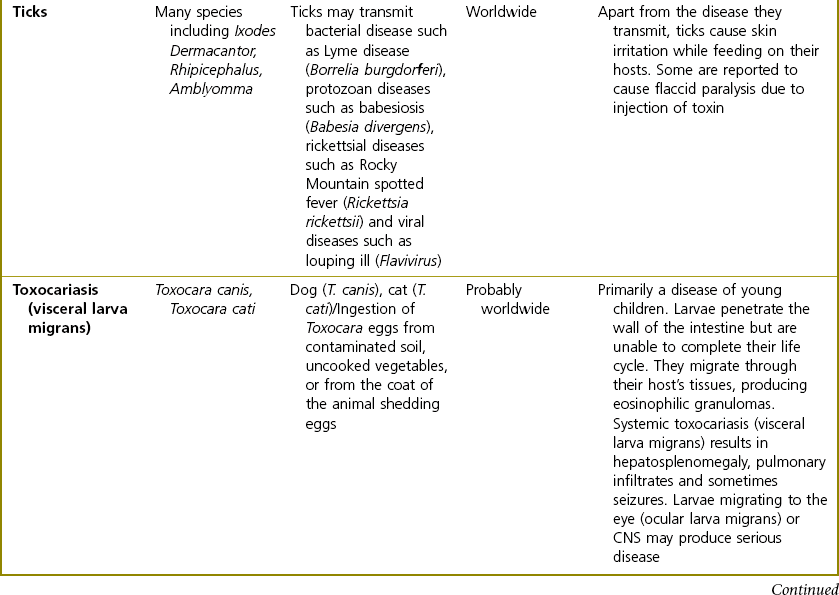

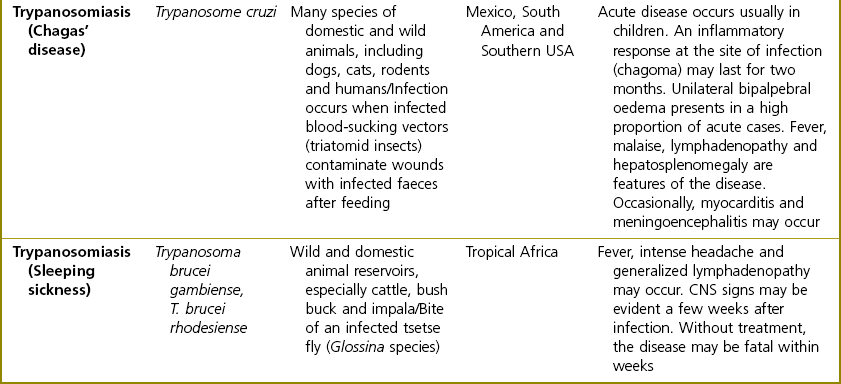

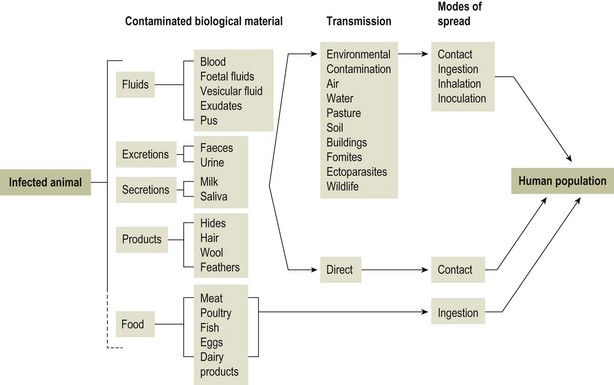

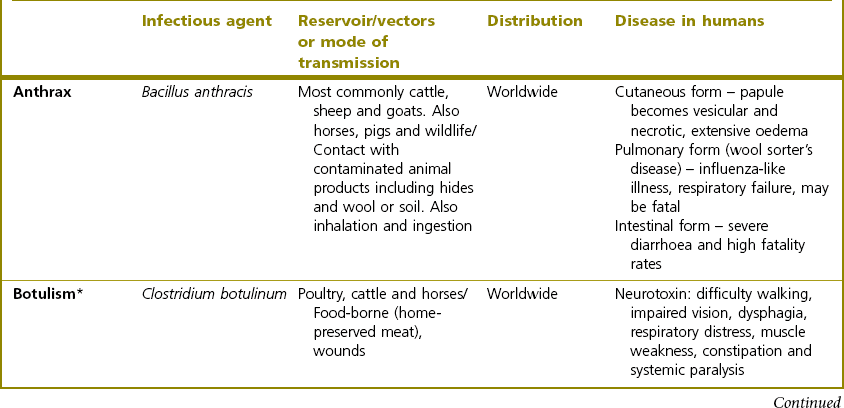

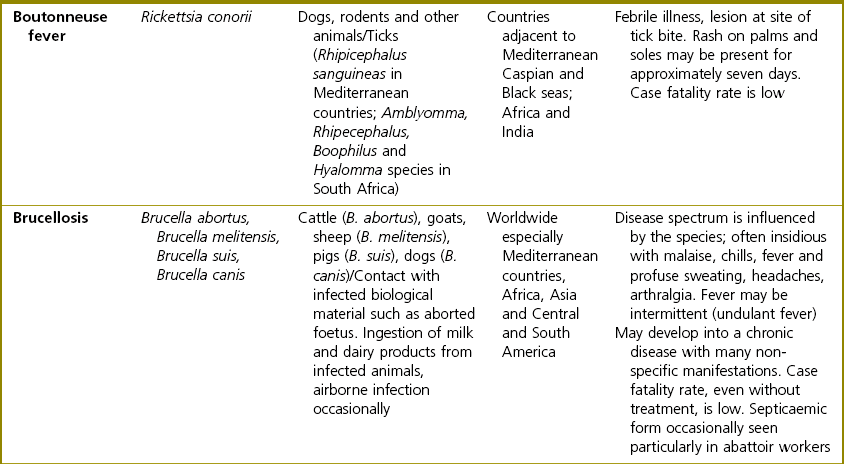

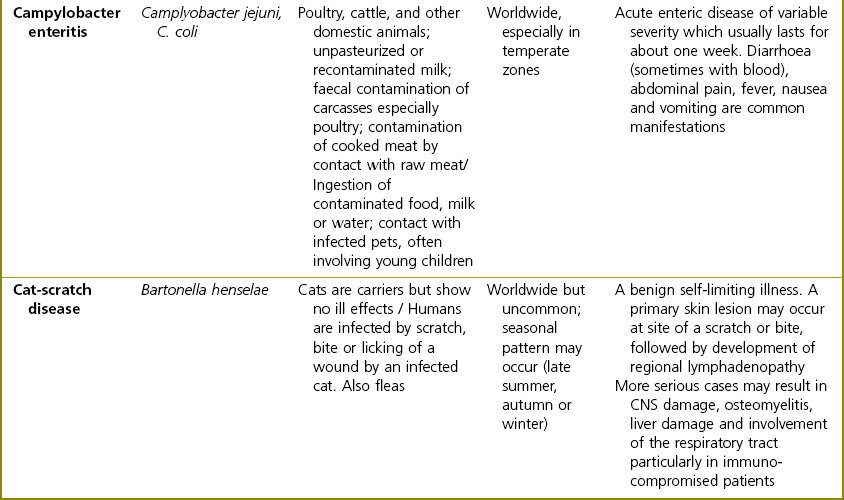

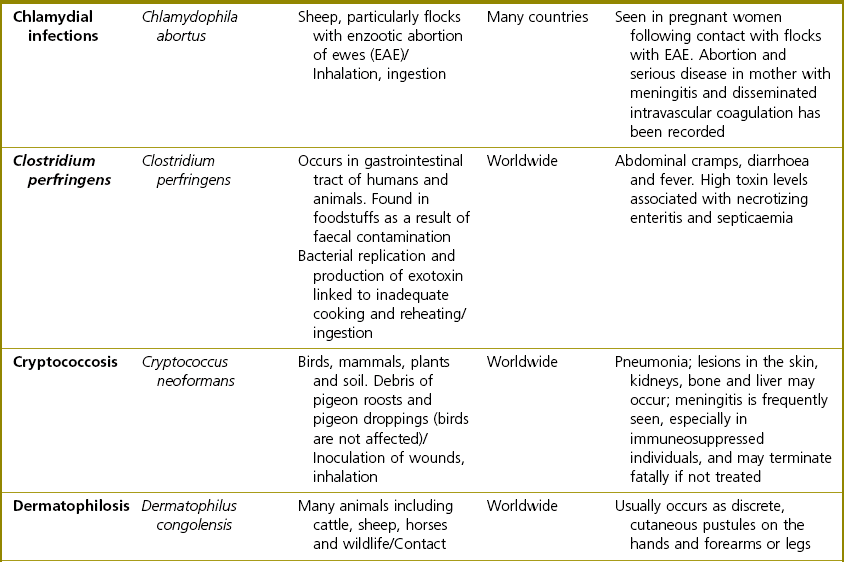

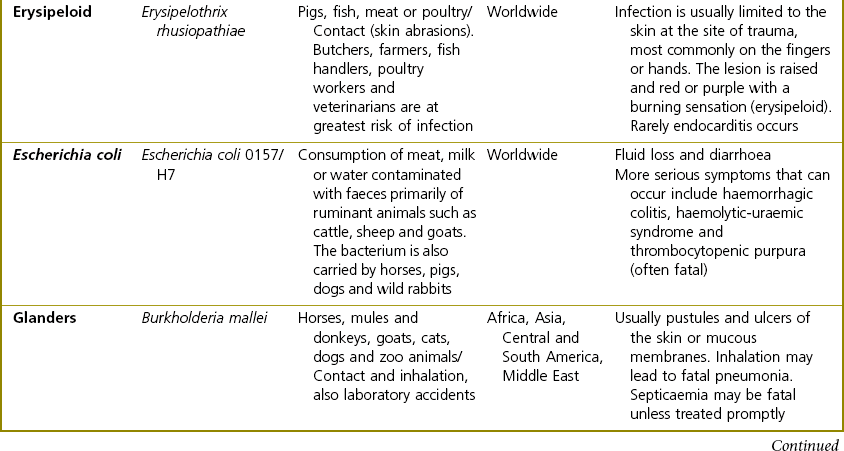

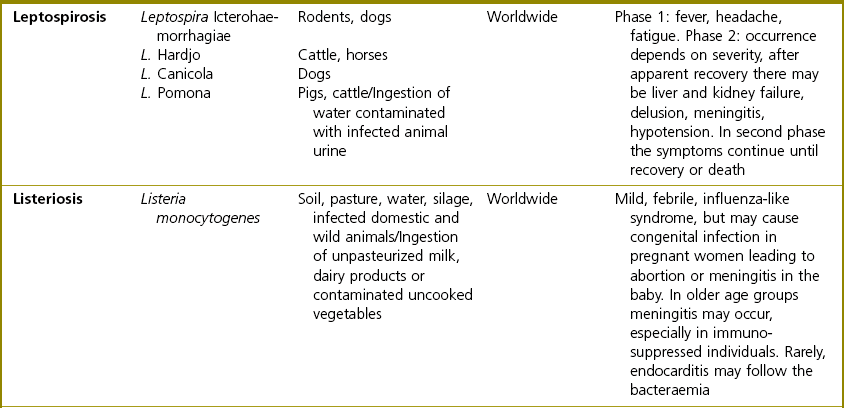

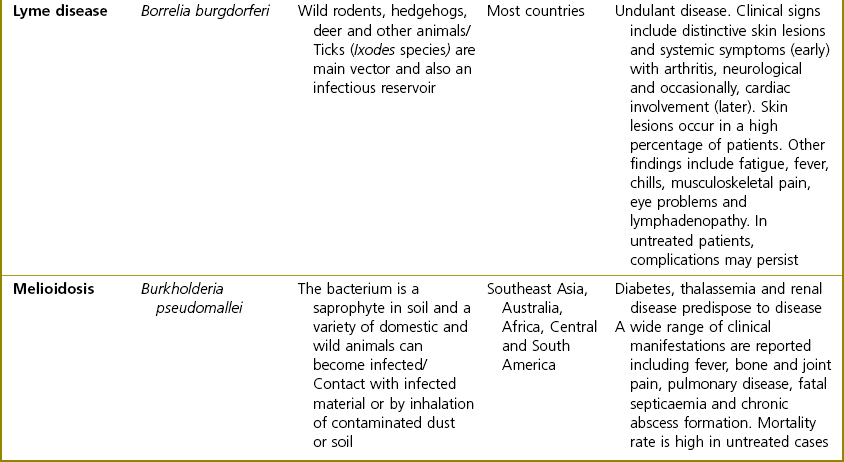

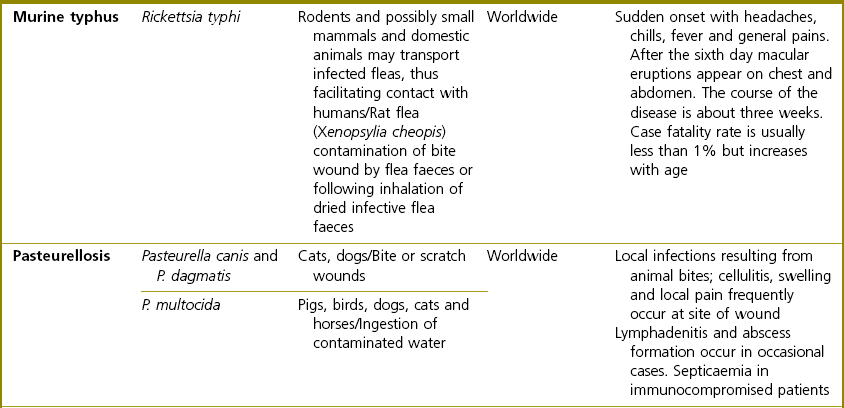

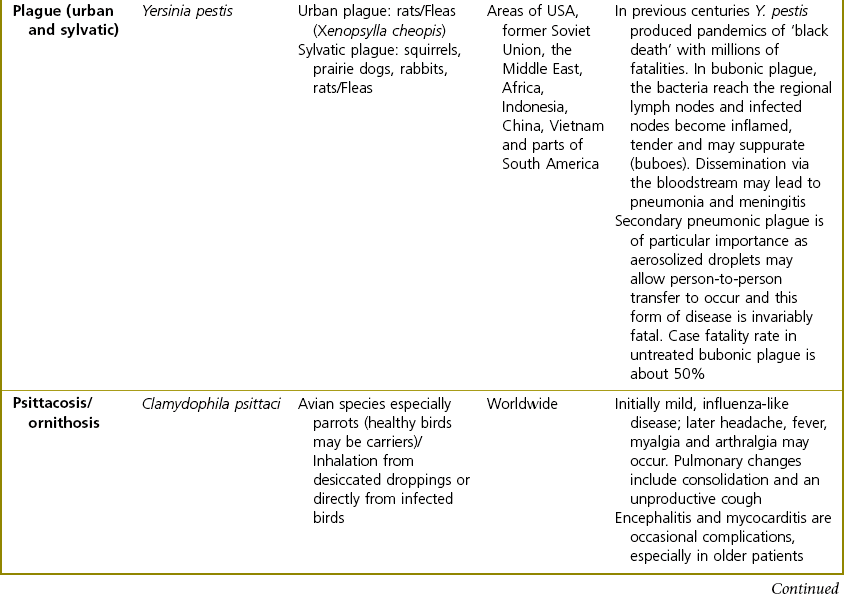

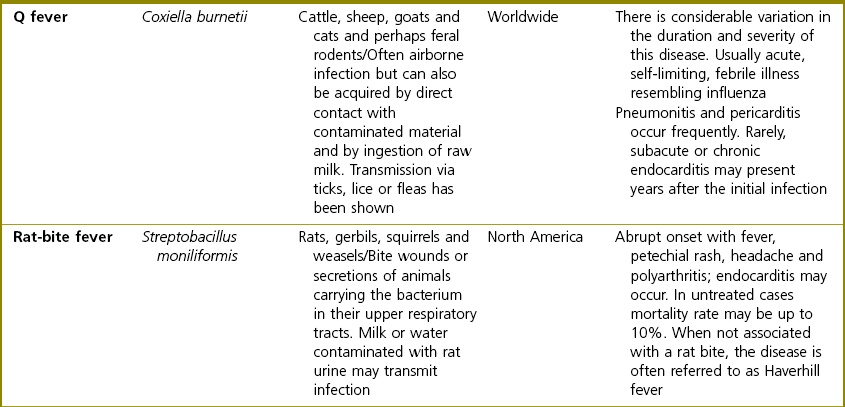

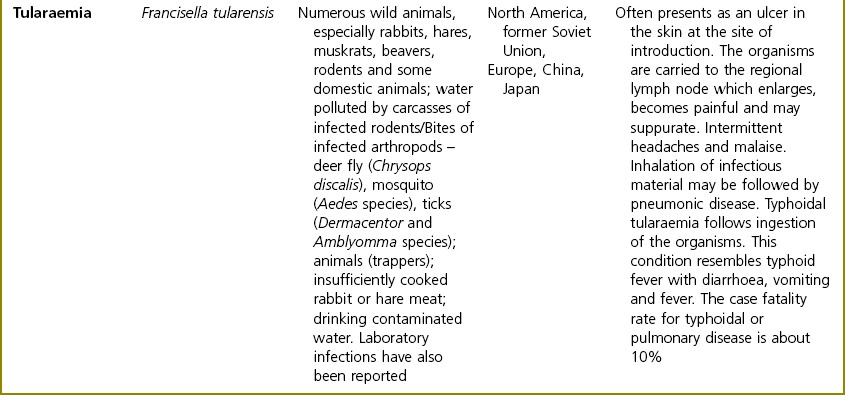

Chapter 68 Transmission of disease may be direct, simply by contact with an animal, or indirect, through food, non-edible products, secretions or excretions (Fig. 68.1). Apart from food-borne zoonoses the importance of particular zoonotic diseases often varies with a person’s occupation, the nature and type of animals present and the diseases prevalent in the animal population in a particular geographical region. The more frequent and direct the contact with animals, the greater the risk of acquiring a zoonotic infection. Farmers, owners of companion animals, workers in slaughterhouses or by-product processing plants, veterinarians and laboratory staff dealing with infectious material, workers in zoos and circuses and personnel engaged in servicing sanitary services are more likely to acquire zoonotic diseases than workers who have infrequent contact with animals. Figure 68.1 Direct and indirect transmission of infectious agents from animals to the human population. Human diseases acquired in this manner are referred to as zoonoses. An analysis of 335 emerging infectious disease (EID) events occurring between 1940 and 2004 revealed a number of interesting global trends (Jones et al. 2008). More than 60% were zoonoses with the majority of these (71.8%) originating in wildlife. The analysis also found that 54% of EIDs were due to bacteria (particularly drug-resistant bacteria) and the threat of emerging infectious diseases to global health has been increasing over time. As international travel and trade have proliferated, disease-causing agents now have the ability to move around the globe at faster rates. Zoonoses may be classified according to their aetiology as being of bacterial, fungal, viral or parasitic origin (Tables 68.1, 68.2 and 68.3). Selected zoonotic diseases in each category are briefly reviewed. Table 68.2 Bacterial, chlamydial, rickettsial and fungal zoonoses *Not strictly a zoonosis, occurs due to ingestion of preformed toxin, or, rarely, due to elaboration of toxin within the body following contamination by spores from the environment Animals vary in their ability to act as reservoirs of zoonotic diseases and also in their ability to transmit infectious agents to humans. Rarely, humans act as definitive hosts of parasites which infect animals. The beef tapeworm Taenia saginata, which is found in the human small intestine and occurs worldwide, is an example of such a parasite. The adult tapeworm which may be up to 10 metres in length, is composed of segments or proglottides which may contain up to 100,000 eggs. Gravid segments may contaminate pasture through sewage disposal, indiscriminate defecation by infected humans in the vicinity of cattle, or by flooding of pasture land with contaminated water. Embryonated eggs which are immediately infective must be eaten by the only intermediate host, cattle, to develop further. Following ingestion by a susceptible bovine animal, the oncosphere, after hatching in the small intestine, travels via the blood to striated muscle and various organs including the heart, tongue and liver. Within three months the cysticerci which develop are infective for humans (Fig. 68.2). Figure 68.2 Taenia saginata: viable cysticerci dissected from the carcase of a heifer experimentally infected with eggs of T. saginata seven months earlier.

Zoonoses

Taenia saginata Infection (Beef Tapeworm)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree