CHAPTER 7 Viral and Protozoal Skin Diseases

Viral diseases

Cutaneous lesions may be the only feature associated with a viral infection, or they may be part of a more generalized disease.1,3,4,14a A clinical examination of the skin often provides valuable information that assists the veterinarian in the differential diagnosis of several viral disorders.

Electron microscopy is very useful in the rapid diagnosis of viral skin diseases, but isolation of the causal virus in tissue culture is more widely used and a more sensitive technique. Immunohistochemistry, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and various molecular biological techniques are increasingly available for the quick, precise diagnosis of the infectious diseases.1,3,4

An in-depth discussion of all the viral diseases—especially their extracutaneous clinical signs and pathology and their elaborate diagnostic and control schemata—is beyond the scope of this chapter. We will concentrate on the dermatologic aspects of the diseases. The reader is referred to other excellent texts for detailed information on the extracutaneous aspects of these diseases.1,3,4

Poxvirus Infections

The Poxviridae are a large family of DNA viruses that share group-specific nucleoprotein antigens.3 The genera include Orthopoxvirus (cowpox and vaccinia), Capripoxvirus (sheep-pox, goatpox, and bovine lumpy skin disease), Suipoxvirus (swinepox), Parapoxvirus (pseudocowpox, bovine papular stomatitis, and contagious viral pustular dermatitis), and Molluscipoxvirus (molluscum contagiosum).

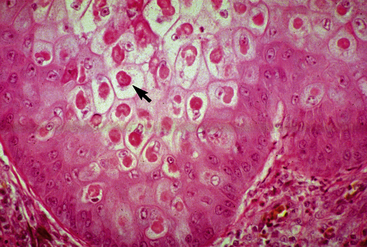

Histologically, pox lesions begin with ballooning degeneration of the stratum spinosum of the epidermis (Fig. 7-1). Reticular degeneration and acantholysis result in intraepidermal microvesicles. Dermal lesions include edema and superficial and deep perivascular dermatitis. Mononuclear cells and neutrophils are present in varying proportions. Neutrophils migrate into the epidermis and produce intraepidermal microabscesses and pustules, which may extend into the dermis. Marked irregular to pseudocarcinomatous epidermal hyperplasia is usually seen. Poxvirus lesions contain characteristic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies, which are single or multiple and of varying size and duration. The more prominent eosinophilic inclusions (3-7 μm in diameter) are called Type A and are weakly positive by the Feulgen method. They begin as small eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions (Borrel bodies) and evolve into a single, large body (Bollinger body). The smaller basophilic inclusions are called Type B.

Figure 7-1 Poxvirus. Koilocytosis (ballooning degeneration) and intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies (arrow).

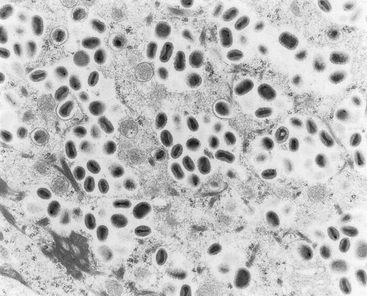

Diagnosis of poxvirus infections is usually based on observation of the typical clinical appearance and may be supported by characteristic histologic lesions. Demonstration of the virus by electron microscopy (Fig. 7-2) will confirm a poxvirus etiology but may not differentiate between morphologically similar viruses, such as the closely related orthopoxviruses. Poxviruses are brick-shaped or oval structures measuring 200-400 nm. Definitive identification of specific viruses requires the isolation of the virus and its identification by serologic and immunofluorescence techniques.

Poxviruses of horses can produce skin lesions in humans.2 The presumptive diagnosis is usually made because of known exposure to horses. Humans having contact with horses (ranchers, veterinarians, and veterinary students) are at risk. Transmission is by direct and indirect contact, and human-to-human transmission can occur. The incubation period is 4-14 days. Human skin lesions average 1.6 cm in diameter and usually occur singly, most commonly on a finger. However, multiple lesions can arise. Solitary lesions may also appear on the face and legs. Regional lymphadenopathy is common, but fever, malaise, and lymphangitis are rare. Skin lesions evolve through six stages and usually heal uneventfully in about 35 days.9 An elevated, erythematous papule evolves into a nodule with a red center, a white middle ring, and a red periphery. A red, weeping surface is present acutely. Later, a thin dry crust through which black dots may be seen covers the surface of the nodule. Finally, the lesion develops a papillomatous surface, a thick crust develops, and the lesion regresses. Pain and pruritus are variable.

Vaccinia

Vaccinia is caused by an orthopoxvirus that infects horses, cattle, swine, and humans.2,3,9,21 The virus is propagated in laboratories and used for prophylactic vaccination against smallpox in humans. In 1979 the World Health Organization declared worldwide eradication of smallpox. Eradication was achieved by the use of a virus believed for many years to have been derived from a lesion on the udder of a cow (the very words vaccine, vaccinia, and vaccination are derived from the Latin word vacca, meaning “a cow”).21 However, from currently available information, it appears that the strain of virus used to inoculate people against smallpox may have come from a horse.2,21

“Horsepox” was a commonly described clinical disease from at least the late eighteenth century until the early twentieth century.2 However, “horsepox” is rarely described recently. Various lines of reasoning—historical, clinical, and experimental—strongly suggest that “horsepox” never existed as a separate entity and was actually vaccinia.2,20,21 Not surprisingly, then, as smallpox was eradicated and the use of vaccinia virus immunization ceased, the disease “horsepox” literally disappeared.

In addition, from the 1940s through the 1970s, there were scattered reports on two other orthopox virus infections of the skin of horses: viral papular dermatitis and Uasin Gishu disease.2 Again, careful comparison of the clinical, histopathologic, and virologic features of these two syndromes with experimentally induced vaccinia in horses indicates that the three conditions are likely the same.2,20,21

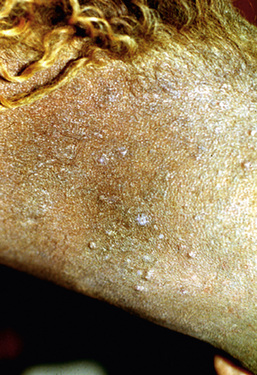

The lesions of equine vaccinia may affect the skin of the muzzle and lips, the buccal, nasal, and genital mucosa, the skin of the caudal aspects of the pasterns, or the entire body surface.2,20 Within 4 days after inoculation of vaccinia virus, raised, discrete, 2- to 4-mm diameter papules are seen.20 These lesions proceed through a typical pox sequence of pustules that develop dark, hemorrhagic umbilicated centers, then scabs, and then scars at about 22 days postinoculation (Figs. 7-3 and 7-4). In haired areas, a thin yellow exudate is produced, which dries to a fine crystalline powderlike appearance and then becomes a thick, yellow to dark brown and greaselike substance that mats the hair. Some horses manifest mild to moderate pyrexia, lameness, depression, ptyalism, and difficulties in eating and drinking.

The virus grows on chicken chorioallantoic membrane or calf kidney monolayers and has typical electron microscopic morphology.2,20 Skin biopsy reveals typical poxvirus histopathologic changes (see earlier).2,20

Molluscum contagiosum

Molluscum contagiosum is caused by a molluscipox virus.9,22 The virus has not yet been grown in tissue culture or in an animal model. The disease is worldwide in distribution. Transmission occurs by intimate skin-to-skin contact and by fomites. Immunoincompetent humans have more severe, unusual, and recalcitrant forms of the disease.

Due to very close homology of their viral DNA sequences, the viruses of equine and human molluscum contagiosum are either identical or very closely related.22 It has been suggested that equine molluscum contagiosum may represent an anthropozoonosis, wherein disease is transmitted from human to animal.22

Molluscum contagiosum has been reported in a number of horses, from 1- to 17-years-old, many of which were in good health.2,15,22 There was no evidence of contagion to contact horses. Lesions usually begin in one body region and become widespread. Most horses have hundreds of lesions (especially on the chest, shoulders, neck, and limbs). However, lesions can remain localized to areas such as the prepuce, scrotum, or muzzle. Early lesions are 1- to 8-mm diameter papules. In haired skin, the papules are initially tufted, but usually become alopecic and covered with a powdery crust or grayish-white scales (Figs. 7-5 and 7-6). Some papules have a central soft white spicule (Fig. 7-7) or firm brownish-yellow horn that projects 3-6 mm above the surface of the lesion. Coalescence of lesions occasionally produces 2- to 3-cm diameter cauliflowerlike nodules or plaques. Some lesions bleed when traumatized. Papules in glabrous skin may be smooth, shiny, hypopigmented, and umbilicated, or hyperkeratotic and hyperpigmented (Fig. 7-8). The lesions are typically nonpruritic and nonpainful.

Biopsy reveals well-demarcated hyperplasia and papillomatosis of the epidermis and hair follicle infundibulum (Fig. 7-9).2,9 Keratinocytes above the stratum basale become swollen and contain ovoid, eosinophilic, floccular intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies (so-called “molluscum bodies”). These inclusions increase in size and density as the keratinocytes move toward the skin surface, compressing the cell nucleus against the cytoplasmic membrane. In the stratum granulosum and stratum corneum, the staining reaction of the molluscum bodies changes from eosinophilic to basophilic. Molluscum bodies exfoliate through a pore that forms in the stratum corneum and enlarges into a central crater (Fig. 7-10

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree