Chapter 4 Veterinary Challenges of Mixed Species Exhibits

Modern zoos like to show larger groups of animals, preferably in natural habitat–like mixed species exhibits, but it is not always easy to combine different species in one exhibit. The size of an exhibit is essential when mixing animals, especially when mixing larger mammals. Aviaries and aquaria are examples with a long-standing experience of combining various species, but in mammals this experience is often poor. Most often, zoos still show single species exhibits because of lack of space or simply to prevent problems associated with mixing different species. Safari parks in Europe were very popular in the 1960s, showing more natural displays of animals. However, because of the difficulties of handling animals in mixed exhibits, many of these parks later closed their gates. The parks that remained and still exist gained experience regarding which species may be kept together with others and which species shouldn’t be mixed. The main advantage of mixed species enclosures is behavioral enrichment (Fig. 4-1) and the obvious educational value. There are even mixed species exhibits of carnivores. For example, Dierenrijk in Nuenen, The Netherlands, combines European grey wolves (Canis lupus) with European brown bears (Ursus arctos; Fig. 4-2) and Gelsenkirchen Zoo, Germany, combines arctic foxes (Vulpes lagopus) with Kodiak bears (Ursus arctos middendorffi; Fig. 4-3).

Trauma

In mixed species exhibits, trauma is the most frequent and serious cause of health problems (Fig. 4-4).6 Competition for nesting sites in birds, establishment of territories, and competition for food and watering stations in all taxa may provoke fighting and trauma in mixed exhibits such as aviaries and large exhibits of mammals. For example, young antelopes born outside will be chased in the beginning of their lives by curious zebras, leading to death or a fatal myopathy, as has also been seen in young or newborn giraffes1 and antelopes. Play of young animals may not be understood by other species (Fig. 4-5). Pinioned birds fly in unrecognizable ways in the eyes of other animals and may become victims of other birds or mammals. Another factor is that when animals are frightened because of thunder or other events, or when animals are chased by other animals because of unexpected or differing circumstances, fleeing against fences or walls may cause fatal trauma.

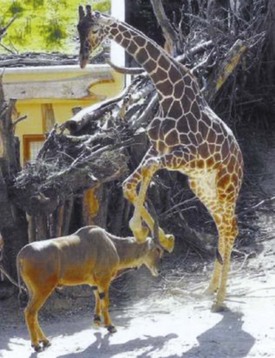

Seasonal aggression, especially in deer (rut), may lead to interspecies conflicts, but different males of the Artiodactylae family will fight intraspecifically over their territory or interspecifically with other animals to protect their herd (Fig. 4-6). Antlers and horns are weapons capable of causing stab wounds, fractures, or even immediate death. Capping horns and cutting of antlers may limit the severity of trauma.6

Figure 4-6 Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) kicking an eland antelope (Taurotragus oryx) with the front legs.

After traumatic injuries, pathologic studies should always be carried out. For example, when birds kill one another, pathology often reveals underlying disease and explains the noticed aggression.6

To prevent trauma, next to appropriate size of the exhibit, pole gates (creeps), where small animals can flee from larger animals, creation of large obstacles in exhibits so animals may circle around these when chased, hiding places, and provision of multiple feeding and watering sources are workable preventive measures when planning mixed exhibits.6 There is no definition of an appropriate size, but for animal welfare reasons and to avoid trauma, exhibits should be as large as possible.

Nutrition-Related Problems

Adequate nutrition is vital for every living being. In mixed exhibits, a sufficient number of feeding stations is essential to ensure that all animals may eat and at the same time prevent that some don’t overeat.6 Also, to prevent interspecies aggression, a sufficient number of feeding stations is necessary. Spreading food over larger areas in aviaries or among hoofstock prevents aggressiveness, and is even more effective when food is provided several times a day.

Requirements of trace minerals and other nutrients such as vitamins differ among species. Deficiencies such as copper deficiency in blesbok (Damaliscus pygargus phillipsi) and sable antelope (Hypotrachus niger), or toxicities such as vitamin E toxicity in pelicans or iron storage disease in birds and some primate species, should be avoided when developing feeding protocols for mixed species exhibits.6 These should incorporate the specific needs and required feeding supplementations of the various species in a mixed exhibit.

Infectious Diseases

Mammals

Malignant catarrhal fever (MCF) is probably the first infectious disease that a zoo veterinarian thinks of when asked about the risks of mixed exhibits. The gammaherpesvirus hosted by wildebeest (Connochaetes spp.), topi (Damaliscus spp.), hartebeest (Alcelaphalus spp.); (Alcelaphine herpesvirus 1 [AIHV-1]), sheep (subfamily Ovinae; ovine herpesvirus 2 [ OvHV-2]) and goats (subfamily Caprinae; caprine herpesvirus 2 [CpHV-2]) is shed (mostly) around parturition and may infect other species. Giraffes (Giraffa camelopardis), muskox (Ovibos moschatus), European and American bison (Bison bonasus and Bison bison), muntjac (Muntiacus species), Pere David’s deer (Elaphurus davidianus), moose (Alces alces), kudu (Tragelaphus spp.) and other deer (Cervidae spp.), gaur (Bos gaurus), and banteng (Bos javanicus) are especially susceptible to these diseases.4,5 In white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), a new MCF virus has been recognized that causes classic MCF. Do not mix wildebeest with giraffes and preferably get rid of all sheep and goats in a zoo collection. Carrier species should at least not be in breeding situations in direct contact or close to susceptible species. There are examples of zookeepers owning sheep at home that transmitted the virus to giraffes, resulting in high mortality.7 It is questionable whether zookeepers should be allowed to take care of household sheep and goats at home.

Equine herpesvirus 1 has led to problems with Bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus), llama (Lama glama), and a Thompson’s gazelle (Gazella thomsoni).6 The virus is shed by infected horses (Equus caballus), zebra (E. grevyi, E. zebra, E. quagga), and onager ( E. hemionus) during respiratory infection, parturition, and abortion. Vaccination is no guarantee for preventing an outbreak. When introducing equids into mixed exhibits, it is advisable to use only seronegative equids.

Mixed exhibits with ruminants should be monitored serologically for diseases such as leptospirosis, brucellosis, infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR; bovine herpesvirus 1 [BHV-1]), bovine virus diarrhea (BVD), tuberculosis (Mycobacterium tuberculosis, M. bovis), paratuberculosis (M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis), leucosis (enzootic bovine leucosis, bovine leukemia virus), neosporosis (Neospora caninum), bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV; e.g., ovine lentivirus, Maedi–Visna)—because most of these diseases spread between different ruminant species. Brucellosis, leptospirosis, and tuberculosis will also affect numerous other mammalian species.4

The following are other mammalian diseases4:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree