Chapter 40 Veterinary Care of Kakapo

The kakapo, Strigops habroptilus (family Strigopidae, subfamily Strigopinae) is a critically endangered endemic New Zealand parrot. Once common throughout New Zealand, the species was brought to the edge of extinction by a combination of habitat loss and predation by introduced rats and carnivores, especially stoats, Mustela erminea, and now survives only on predator-free off-shore islands.11,25 From a low of 51 in 1995, intensive management by the New Zealand Department of Conservation (DOC) has increased the number to 123 as of March 2010. The current rarity of this species has meant that few veterinarians have had the opportunity to work with kakapo. However, this is changing as the numbers continue to increase and DOC is placing greater emphasis on the display of the species for educational and advocacy purposes. Our objective in this chapter is to provide information for the guidance of clinicians faced with the opportunity to provide veterinary care for this unique species.

Unique and Unusual Features

The kakapo is flightless and nocturnal and has the biggest body mass and most extreme sexual dimorphism of any parrot. Males weigh 1.6 to 3.6 kg (mean, 2.11 kg) and females weigh 0.9 to 1.9 kg (mean, 1.45 kg).13,25 Average seasonal weight gains can be as much as 23% to 25%, but individuals can fluctuate by 100% in the course of a year.12 The ventral surface of the strong broad rhinotheca is equipped with transverse serrations used, with the tongue, to crush and extract nutrients from a wide range of leaves, fruits, seeds, grasses, fern fronds, and rhizomes that comprise its herbivorous diet.8,30 The crop is unusually large and pendulous to accommodate this highly fibrous, low-nutrient diet. When full, it overlies the thorax ventrally, where the birds have the markedly reduced keel and pectoral muscle mass associated with their inability to fly. The simple gut includes a relatively thin-walled gizzard and no caecum.

Behavior and Reproduction

Perhaps the most unusual aspect of this bird’s biology is its lek mating system. This involves the construction, maintenance, and defense, by the male, of a display territory known as a track and bowl system. These are usually located on an elevated site and are comprised of one or more shallow excavations (bowls), linked by clearly defined tracks. The male stands within the bowl and, after massively inflating his cervicocephalic air sacs, emits a series of low-frequency booms that may be heard for a distance of up to 5 km.25 This serves to proclaim territory and attract females for mating. Females subsequently lay a clutch of two to four eggs in natural holes or cavities at ground level within their own home range. The male takes no part in the incubation of eggs or rearing of the altricial chicks, which hatch after 30 days.13

There is some indirect evidence to suggest that kakapo are very long-lived. Clout9 has speculated that some may survive for over a century. Breeding is irregular and occurs only every 2 to 7 years, stimulated by the fruiting of podocarp trees, especially the rimu, Dacrydium cupressinum, whose protein-rich seeds and fruit form the basis of the diet on which the chicks are reared.10,25,30 Males reach sexual maturity at approximately 5 years of age and females by at least 6 years.12

Hospitalization

Only one adult kakapo, a human-imprinted male, has been publicly displayed in captivity to date. Although some individual adult birds have been hospitalized for extended periods of up to several months, it can take several weeks before they settle enough to self-feed. Consequently, daily supplementary feeding with a crop tube is required to ensure adequate nutrition. When this is necessary for prolonged periods, either a stainless steel crop tube or a soft flexible tube (26-Fr Foley catheter) inserted through an oral gag can be used to minimize trauma to the upper gastrointestinal mucosa. Harrison’s neonate, juvenile, and recovery formulas (HBD International, Brentwood, Tenn) provide adequate nutrition for weight gain and maintenance of body condition but the thick consistency of this food requires the 26-gauge soft tube. Kaytee Exact hand-rearing formula for macaws (Kaytee Products, Chilton, Wisc), mixed at 28% solids, is equally effective and can be fed through a stainless steel crop tube. The capacious crop can accommodate up to 70 to 100 mL comfortably in most adult birds. Twice-daily feeds are given initially and the evening feed is gradually reduced to encourage normal nocturnal self-feeding on a variety of native browse supplemented with apples (Malus domesticus), kumara (sweet potato, Ipomoea batatas), and carrots (Daucus carota subsp. sativus). To minimize fecal contamination, food can be provided in hoppers placed at the bird’s head height. These are used to supplement free-living birds who readily learn to lift the lid that excludes other wild birds. Similarly, young birds readily learn to drink from up-turned sipper bottles with metal tubes that provide controlled water flow.29 For adults, water is supplied in a shallow dish or an up-turned water hopper, as used for poultry.22 It is important for this solitary cryptic species that they be provided with a quiet environment that provides opportunities to hide under large, up-turned leafy branches of nontoxic native plants, which also provide the birds with climbing, roosting, and chewing opportunities (Fig. 40-1). Kakapo do not tolerate prolonged environmental temperatures above 25o C (77o F).

Because the aim of hospitalization is to rehabilitate sick or injured kakapo for return to the wild, strict hygiene and quarantine barrier techniques must be used to minimize risk of nosocomial infections being inadvertently transferred to the wild population. On admission, it is standard practice to run a full health screen comprised of a physical examination (including body weight and examination for ectoparasites), complete blood count, avian biochemistry panel, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay for psittacine circovirus (PBFD), immunoassay for Chlamydophila, fecal wet preparation and flotation for gastrointestinal parasites, and whole-body lateral and ventrodorsal radiographs. The PBFD test is repeated just prior to discharge. The captive care of juvenile birds has been described in detail by Eason and Moorhouse.14

Restraint

Physical

Reference ranges for hematology and serum biochemical analysis have been published for wild kakapo.6,18 For venous access, the medial metatarsal, brachial, and jugular veins have all been used successfully. Microscopic examination of crop washes and fecal smears also differs from other parrots in that kakapo have mixed gram-positive and gram-negative gastrointestinal flora, low numbers of budding yeasts (Candida famata, C. guilleamondi), and flagellated protozoa, similar in morphology to Trichomonas spp,. are commonly seen in samples from healthy wild birds.

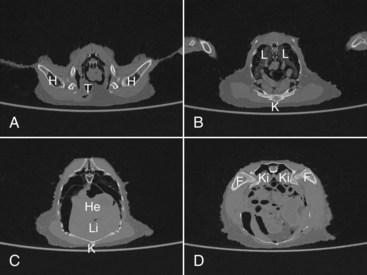

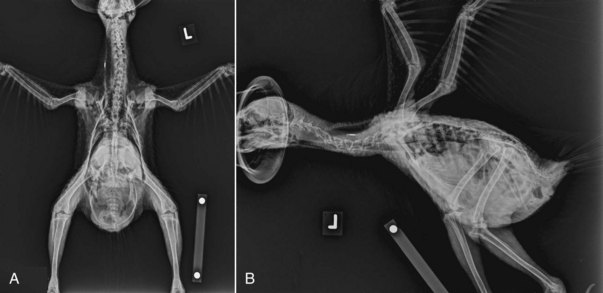

Diagnostic Imaging

Diagnostic imaging modalities that have been applied to kakapo include radiography, ultrasonography, laparoscopy, and computed tomography (CT). Ultrasonography and echocardiography have been carried out with the kakapo conscious but all other modalities require general anesthesia to obtain images of acceptable diagnostic value. Standard techniques were used for these modalities and normal examples of radiographs and CT scans from healthy kakapo are illustrated in Figures 40-2 and 40-3. Imaging anatomy mirrors the anatomic peculiarity of the species with the large pendulous crop, minimal keel and pectoral muscles, and a strong appendicular skeleton (see Fig. 40-2). The lungs of kakapo differ from those of other parrots on CT in that there appears to be a network of large parabronchi close to the ribs, but the significance of this finding is uncertain (see Fig. 40-3).

Figure 40-2 Radiographic anatomy of a juvenile male kakapo in lateral and ventrodorsal positioning.

(Courtesy Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree