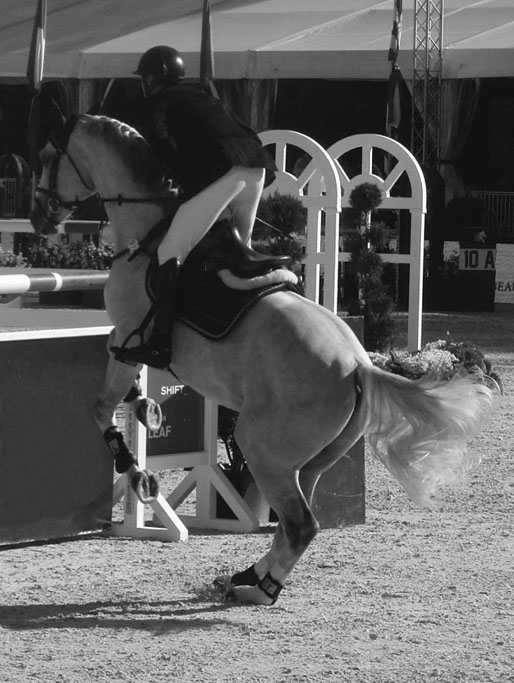

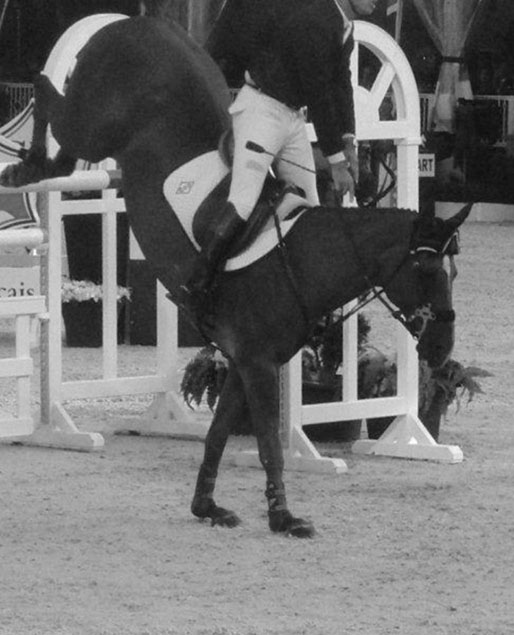

Show jumping is primarily a power sport, requiring a variety of skills in association with power and fitness. The cantering between fences has primarily aerobic demands, while each jumping effort significantly increases the heart rate above that needed for cantering between fences and appears to have additional anaerobic demands, particularly in horses with poor jumping fitness.1,2 Show jumpers with efficient jumping technique, however, may use primarily aerobic metabolism. Fitness training therefore needs to improve aerobic capacity and power. Heart rate during show jumping has been reported as approximately 180–206 beats per minute during a jumping round.1,3 In one study, jumping a spread fence during warm-up was associated with a higher heart rate than jumping an upright fence, which was suggested to result from a faster approach to a spread fence or increased power requirement. Heart rate tends to increase during the round to a maximum at the end, with heart rate recovery starting immediately at the end of the course.1,2,4,5 Jumping a course has been associated with an increase in packed cell volume, consistent with splenic contraction.2,5,6 Blood lactate concentrations of around 3–8 mmol/L have been reported after jumping.1,3,7 Based on these lactate concentrations, active trotting recovery has been recommended to increase lactate clearance from muscles.1 Less experienced horses tend to have higher blood cortisol concentrations, possibly indicating a higher level of exercise-associated stress when compared to more experienced horses.7 To clear the jump, the horse’s center of gravity is required to be raised high enough above the fence. The movement of the center of gravity and flight path is determined by the approach and take-off, which are critical in the success of the jump.8 In the final approach stride, the forelimbs are required to brake and provide vertical forces for takeoff, so loading the support structures of the limb and extending the distal limb joints. The trailing forelimb experiences the highest peak vertical forces at take-off.9 The force for take-off is generated by muscular power in the hindlimbs, while the head and neck are raised to optimize power generation.8,10,11 At take-off, there is flexion of the tarsal joints and extension of the metatarsophalangeal joints with a longer hindlimb stance duration than during a normal canter stride, allowing generation of large impulses (see Fig. 55.1). Frequently the hindlimbs may push off together, an equal distance from the fence. The higher the fence, the greater the vertical force required at take-off.9 For spread fences, the hindlimb push off is greater than for an upright fence of the same height.12 A successful jump needs high stride frequency into the fence and high acceleration pulse of the forelimbs and hindlimbs at take-off.12 Faults are less likely to occur when take-off is further from the fence.13 On landing after a jump, there is a significant increase in the forelimb ground reaction force compared to normal canter.9 The metacarpophalangeal and distal interphalangeal joint are hyperextended on landing, resulting in strains on the superficial and deep digital flexor tendons and the suspensory ligament (see Fig. 55.2). The superficial digital flexor tendons of the forelimbs undergo repetitive loading during jumping and considerable strain on landing, with relatively greater strain after jumping higher fences,14 so it is likely that this potential overload predisposes the tendon to injury in elite horses jumping high fences. The deep digital flexor tendon plays an important role in stabilizing the distal interphalangeal joint, which is hyperextended on landing from a jump and therefore experiences considerable loading.15 In the forelimb, landing puts greater strain on the trailing forelimb than the leading forelimb,9 so a horse that with pain or less strength in the left forelimb, for example, may choose to approach and depart from the fence leading with the left forelimb. The departure stride is usually four time, with greater propulsive force generated by the trailing hindlimb.9 Faults are less likely to occur when the trailing hindlimb lands closer to the fence.13 Individual horses have different jumping techniques. However, certain characteristics seem to be retained within an individual horse between a foal and a four year old.16 Horses with greater jumping ability have been reported to show a lower displacement of the withers and tuber sacrale from the end of the last approach until the first departure stride during free jumping. Instead, they increase the flexion of the thoracolumbar and lumbosacral junctions during the hindlimb swing phase before take-off, indicating a more efficient jumping technique.17 Training influences the take-off and landing distance, bascule and height of the forelimbs above the fence.18 Early jumping training has been shown to improve the efficiency of jumping by lower acceleration during the hindlimb push, lower velocity at take-off and less push forward of the center of gravity over a fence.19 From an exercise physiology point of view, training increases aerobic capacity, and excitability and power output of the muscle by increasing the proportion of the oxidative muscle fibers.10 Jumping training at an early age leads to increased adaptation of the middle gluteal muscle in particular.10 The rider has a large effect on the horse, exerting measurable effects on the horse’s center of gravity, change in velocity and acceleration, and kinematics of the joints.18,20 The combined weight of rider and saddle influences jumping kinematics.21 Increased weight results in the leading forelimb landing closer to the fence, with increased extension of the fetlock and carpal joints, increasing the loading on the superficial digital flexor tendon and suspensory ligament. On the first departure stride, increased weight leads to increased stance duration in the hindlimbs and the head further in front of the vertical on landing. Show jumping horses are increasingly Warmbloods, compared to historically where Thoroughbred and Thoroughbred cross horses predominated.22,23 Currently, the trend appears to be for primarily lighter weight Warmblood horses, rather than the more traditional heavier weight type. There is some research indicating that locomotory muscles of good jumpers have a higher proportion of fast myosin heavy chains than less talented horses, particularly in the middle gluteal muscle.3 Features of gait that are associated with better show jumping performance are a higher stride frequency and less deceleration in the last stride before jumping, suggesting more hindlimb power with less forelimb braking.3 Show jumping horses tend to be taller than in many other sports, giving the advantage of longer levers to jump and cover the ground.23 Height at the withers is the conformational characteristic that has been most consistently connected with successful jumping performance.8 Elite show jumpers are reported to have larger hock angles and smaller fetlock angles than other horses.24 In a study that compared horses at elite and lower level, elite horses had lower bodyweight than the non-elite horses, indicating a higher fitness level.22 Elite horses were older than non-elite animals, reflecting the time taken in the training and development of elite horses.22 Jumping horses can start competing as four year olds, often in young horse classes. Performance ability and competition level increase to high-level performance from around nine years and to a peak at 12–13 years of age. Horses may continue competing into their late teens. Older, experienced horses may become schoolmasters for less experienced riders. These older horses may therefore have additional management requirements in order to maintain optimal performance, and close monitoring of tissues at increased risk of injury with age, especially the digital flexor tendons, is indicated. Mares, geldings and stallions are used for show jumping. Results of one epidemiological study indicated that stallions were the most likely gender to go clear while mares were the most likely to have refusals.25 Jumping horses are reported to have generally lower excitation levels and less interest in new objects than dressage horses,26 which may relate to their initial selection or ongoing management. In various countries, horses are bred specifically for jumping. Performance criteria that have been used for selection of breeding stock and their offspring include grading of jumping technique in young horse classes, success in classes at elite level and longevity of performance. Particular bloodlines within various breeds are considered to improve potential for high performance and longevity of performance. In Dutch and German Warmbloods, there was good heritability for free jumping technique, which tended to be higher than the heritability for jumping under the rider.27 In French show jumpers, moderate heritability was shown for annual earnings and ranking records, while there was high heritability for performance tests in young horses using a subjective scoring of ability.3 However, there was only low-to-moderate heritability for performance in Hungarian show jumping horses.28 It is likely that this relates to the variations in training and performance between riders and trainers of different ability and experience. It is accepted that there are differences in riding technique and horse–rider harmony between experienced and novice riders. This has recently been quantified further,29 illustrating the variation in jumping technique between riders of different ability and therefore the variable influence on the horse which impacts the horse’s jumping performance. Longevity of sport horses in jumping competition has been reported to be influenced by age of starting competition, with horses starting competition at four years of age being more likely to stay in competition longer than horses starting at six years of age. Less successful horses were less likely to stay in competition, and mares were more likely to be removed from competition than geldings with the same performance, potentially because they could be used for breeding.30 In another epidemiological study, horses performance peaked at the age of 12–13 years and performance decreased with age in older horses.25 Nutrition of the show hunter and show jumper needs to be tailored to its level of work, stage in the season and temperament, along with its age and stage of training. For horses competing in more than one class in a day, or competing repeatedly over 3–4 days, it is important to consider energy reserves, both in relation to muscle glycogen depletion and replacement.31,32 Forage is the primary component of the rations but concentrate feed is usually required to ensure that energy requirements are met. The quantity and composition (e.g. relative amounts of starch vs oil as sources of energy) can be tailored to individual temperament, workload and competition schedule. For horses at risk of gastric ulceration, access to forage and avoiding large starch-based meals (e.g. no more than 1.5 g starch/kg BW per meal) may be beneficial. For optimal performance, it is recommended that horses are not fed any large cereal-based meals less than 2–3 hours before exercise and they should certainly be avoided close to the time of jumping.31,32 Large concentrate feeds can lead to a decrease in plasma volume, increase in blood insulin and decreases in blood glucose, which could reduce performance. However, giving access to small amounts of hay until the time of exercise may help to maintain gastrointestinal function and minimize risk of gastric ulceration. There has been a recent trend for using tight or weighted boots, which are now affected by FEI regulations (a maximum weight of 500 g per limb is allowed for bandages or boots). Use of weighted boots has been shown to increase hindlimb elevation over a jump, which has been attributed to increased kinetic energy produced by the effect of the weighted boot on the hindlimb.33 Use of weighted boots at walk has been suggested for increasing strength of lumbar musculature.34 However, their use during jumping could potentially increase risk of injury to hindlimb structures or overstrain of the lumbar flexor musculature as a result of exaggerated movement.33 Studs, or shoe caulks, are frequently used in jumping horses to improve grip, particularly on slippery surfaces. Whether these are used, as well as the type and location of the studs within the shoes, tend to be based primarily on rider preference as there is limited scientific evaluation of stud use. Studs alter foot–ground interaction, significantly reducing slip, particularly in the trailing limb at canter.35 Although considerable slip may be detrimental, a small amount of slip on landing after a jump or at each canter stride may be beneficial and is considered to be one mechanism by which energy is dissipated when the foot impacts the ground.36 This varies on different surfaces and may be influenced by stud placement.37 If energy dissipation is not achieved by slide, or alteration in ground surface, then the structures of the limb may experience abnormal forces which could potentially increase risk of injury.38,39

Veterinary aspects of training the show jumping horse

Exercise demands

Biomechanics of jumping

Type of horse

Nutrition

Horse clothing/tack

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Veterian Key

Fastest Veterinary Medicine Insight Engine