Chapter 25 VAGINAL DEFECTS, VAGINITIS, AND VAGINAL INFECTION

CONGENITAL ABNORMALITIES OF THE VAGINA AND VULVA

Embryonic Development

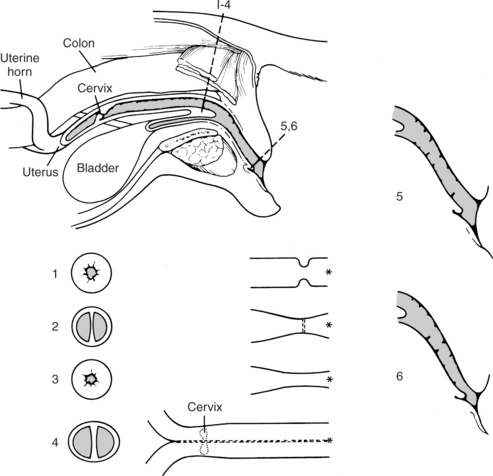

Five major types of abnormalities in embryonic development of the vaginal vault have been reported in the dog, each resulting in a narrowing of the tract, called a “vaginal stricture” (Wykes and Soderberg, 1983). These five abnormalities include (1) a band of fibrous tissue crossing and narrowing the lumen of the vagina (Fig. 25-1); (2) an annular fibrous ring compressing the vaginal lumen (Fig. 25-2); (3) vulvar hypoplasia (immature vulva) that narrows the opening of the vulva; (4) incomplete fusion of the two müllerian ducts causing a “double” vagina (Fig. 25-3); and (5) hypoplasia of the vaginal vault (as opposed to hypoplasia of the vulvar opening).

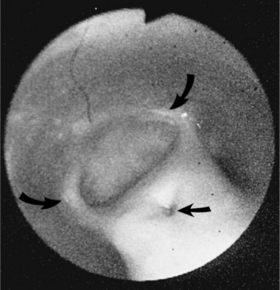

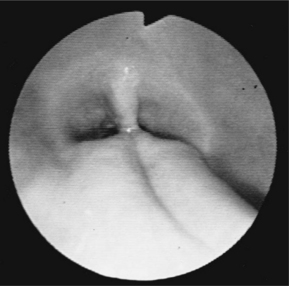

FIGURE 25-1 Endoscopic photograph of a vertical band (congenital defect) causing a vaginal stricture in a bitch.

Of the five abnormalities described at the junction of the vagina and vestibule usually, two are quite common and either may result in an obstruction and cause clinical signs. These problems are almost always detected immediately proximal or cranial to the urethral opening into the vaginal vault, the site of embryonic external and internal genitalia fusion. One is a vertical septum or fibrous band of tissue that crosses the lumen of the vaginal vault (Root et al, 1995). Although not always vertical or central in location, most of these fibrous bands extend from the dorsal midline to the ventral midline, bisecting and compressing the lumen (Fig. 25-4). Vertical bands may represent persistence of a mesonephric duct (Harvey, 1998). The second most common obstruction is the presence of an annular fibrous structure in a similar area of the vaginal tract. This form of fibrous band usually involves the entire circumference of the lumen (Figs. 25-2 and 25-4). Occasionally, the veterinarian may identify an annular ring close to the entrance to the vestibule, located barely within the vulvar folds (Fig. 25-4). This latter obstruction may represent hypoplasia of the genital canal at the vaginal entrance. This defect has also been referred to as an immature or infantile vulva (Mathews, 2001). Regardless of the name, these defects both involve a narrowing of the lumen, although they each represent a different embryonic defect (Holt and Sayle, 1981).

In addition to these common defects, incomplete fusion of the two müllerian ducts can result in an elongated vertical vaginal band extending from the region of the urethral orifice cranially for variable distances. This septum may be short or long, bisecting the vagina, cervix, and uterine body (Figs. 25-3 and 25-4). This condition may be called a “double vagina” (Wykes and Soderberg, 1983; Root et al, 1995). The least common defect is hypoplasia of the vestibulovulvar junction, causing the lumen of the vaginal vault to narrow, perhaps as a result of imperfect joining of the genital folds and genital swellings (Fig. 25-4).

Clinical Signs

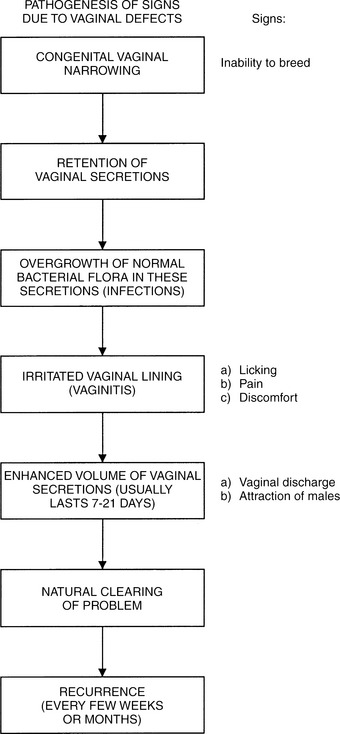

A large percentage of bitches with vaginal or vulvar strictures have no problems related to this defect at any time during their lives. Bitches with any of the above defects that do have problems are usually brought to veterinarians for one, two, or all three of the following owner concerns: (1) vulvar discharge, (2) chronic vulvar licking, or (3) attracting male dogs. These three signs are the result of vaginitis, usually chronic and/or recurring, caused by the stricture. Inflammation of the vaginal mucosa results in increasing vaginal secretions (discharge), irritation causes the licking, and both of these problems, along with bacterial overgrowth, cause odors that attract males (Fig. 25-5). Additional common signs noted by owners include urinary incontinence and recurrent urinary tract infection (Kyles et al, 1996; Crawford and Adams, 2002).

Much less commonly, an owner seeks veterinary attention because a bitch is unwilling to breed, is unable to breed, or appears to be in pain when the male attempts or succeeds in breeding. Less common owner concerns include signs related to urination—dysuria and incontinence. Some owners have noted ambiguous genitalia. The least common owner concern, but perhaps most worrisome, is dystocia (Root et al, 1995).

Inability to breed is an uncommon reason for owners to seek veterinarian care, because most female dogs owned in this country have had an ovariohysterectomy and have never been bred. Therefore the defects described herein are diagnosed in our clinic far more often in spayed than in intact bitches. Lack of breeding may be important in the perceived incidence of these defects in spayed bitches, because the male may break down some of these structures when penetrating the female.

Chronic vaginitis or recurring urinary tract infections are potential sequelae to vaginal obstructions, sometimes causing the bitch to lick at the vulvar area excessively because of pain or discomfort. Vaginitis probably results from chronic retention of a small amount of normal vaginal secretions (±urine?) present in any bitch. If the defect prevents normal clearing of these secretions, they have the potential for serving as a medium for bacterial overgrowth. Therefore the problem is one of retained vaginal secretions followed by overgrowth of the normal bacterial flora and subsequent irritation of the vaginal lining or ascending urinary tract infection. These problems result in licking and increased volume of vaginal secretions. The vaginal secretions usually cause a vaginal discharge and attraction of males. These problems are typically self-limiting, perhaps due to eventual natural clearing of the overgrowth due to the volume of the secretions. Thus the irritation can naturally but transiently resolve, but the underlying cause remains (Fig. 25-5). Bacterial overgrowth within the vaginal tract is often implicated as causing ascending infection of the lower urinary tract.

The clinical signs of vaginitis caused by vaginal stricture typically wax and wane, being difficult to eliminate but rarely causing systemic illness. The entire described process usually repeats itself every few weeks or months, sometimes becoming more frequent or severe, causing owners to seek veterinary assistance. Rarely, an owner may believe that his or her bitch is experiencing an ovarian cycle because of the attraction of males. The odor created may cause this attraction, but the bitch does not allow the male to mount.

Diagnosis

THE OVARIOHYSTERECTOMIZED BITCH.

The diagnosis of any vaginal obstruction (vulvar stricture or vestibulovaginal stenosis) is best made with digital examination of the vaginal vault. Normally, a gloved and lubricated index finger can be passed into the vaginal vault, without pain or difficulty to the bitch, in all but the most miniature breeds (Harvey, 1998). Remember that the veterinarian’s finger is invariably smaller than the erection of the male of that breed. Therefore digital examination of the vaginal vault should be able to be completed without difficulty. If a stricture is suspected, one should proceed slowly and gently in order to avoid causing pain to the bitch. Sedation or anesthesia of the bitch is almost never used, being reserved for those dogs that become vicious when the vulvar area is examined.

VAGINOSCOPY.

Use of a fiberoptic pediatric proctoscope (see Fig. 25-1) can be an excellent diagnostic aid in visualizing a vaginal defect. Although these instruments are useful diagnostic tools, they are not as sensitive as the digital examination. Use of a vaginogram (radiographic dye study) has been recommended, especially when surgical correction of a vaginal defect is being considered and vaginoscopy is not available (Wykes and Soderberg, 1983; Root et al, 1995; Mathews, 2001; Crawford and Adams, 2002). This procedure has been beneficial diagnostically in some bitches because it has the potential of confirming a diagnosis, defining the location, and identifying a major defect such as a “double vagina” (Fig. 25-3) or a less extensive defect, such as an annular ring (Fig. 25-2).

RADIOLOGY.

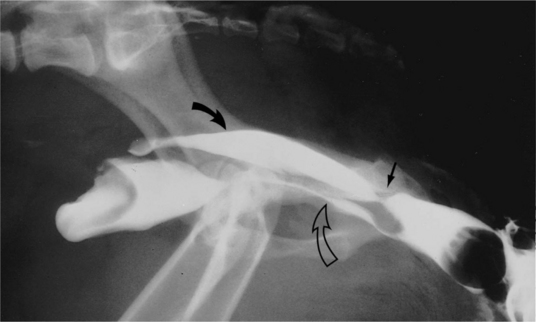

If vaginoscopy is not available, a radiographic dye study (vaginogram) is an alternative diagnostic aid. This tool is used in a bitch suspected of having a vaginal stricture not palpable because of its location (this is extremely unusual). We have used the vaginogram in bitches with vulvar hypoplasia because one cannot pass a finger or an instrument through the area of hypoplasia without causing pain or trauma to the bitch. Another indication for a vaginogram is a palpable stricture that prevents evaluation of the cranial vagina (Fig. 25-6). Before surgery or other therapy is considered, evaluation of the entire vagina may be warranted to rule out unsuspected abnormalities (polyp, tumor, foreign body, extensive congenital defect; see Figs. 25-3, 25-4, and 25-6). Furthermore, other congenital anomalies (e.g., urethral ectopia, pelvic bladder) should be ruled out. A urethral pressure profile should be considered (Mathews, 2001).

The bitch should be anesthetized for the vaginogram. A Foley catheter is placed in the vestibule of the vagina. The balloon is inflated, and a volume of dye is injected through the catheter into the vaginal vault. Radiographs can then be taken to determine whether enough dye has been injected to provide an adequate study. Determining the required volume of dye is a challenge, because it is difficult to predict what amount of dye will pass into the urinary bladder. One report describes a method of “grading” a vestibulovaginal stenosis (vaginal stricture). On review of radiographic cystourethrovaginograms, measurements were made. The dorsoventral height of the vagina was measured at its highest point, and the dorsoventral height of the vestibulovaginal junction was measured at its narrowest point on a lateral radiograph. The ratio of the height at the vestibulovaginal junction to the height of the vagina was calculated. A ratio >0.35 was suggested as normal. Ratios of 0.26 to 0.35 were classified as “mild,” 0.20 to 0.25 as “moderate,” and <0.2 as “severe” vestibulovaginal stenosis (Crawford and Adams, 2002).

Therapy

THE BREEDING BITCH.

No treatment is recommended if the diagnosis of vaginal obstruction is made in a bitch without clinical signs. A bitch thought to have a vaginal obstruction may breed normally or be artificially inseminated. The artificially inseminated bitch requires close observation to be certain that a vaginal dystocia does not occur during whelping. The fibrous band defects are the easiest to correct because they can be isolated and incised without much difficulty or bleeding. Normal parturition may occur in the bitch with an annular ring if enough relaxation of the vaginal walls allows passage of the newborn through the narrowed area or if the obstruction is broken down during parturition. It is not known whether these defects are inherited, and some have suggested that their surgical correction would be unethical (Harvey, 1998).

Where indicated, correction of congenital vaginal ring obstructions can be accomplished surgically. In most cases, an episiotomy is necessary to provide adequate visualization of the defect. Postsurgical dilation of the vaginal vault may be required to prevent recurrence of vaginal strictures. In addition, correction of vaginal defects does not ensure that the bitch will subsequently allow breeding. (The interested reader should consult surgical references for the necessary procedures: Greene, 1983; Wykes and Soderberg, 1983; Mathews, 2001.) Antiseptic douches can be used as described in the following section.

THE OVARIOHYSTERECTOMIZED BITCH.

Most bitches diagnosed with defects associated with their vaginal lumens have been previously spayed. Before making any treatment recommendation, the owner should be educated with a complete discussion and illustration, such as that in Fig. 25-4. In this manner the owner can understand the problem and can appreciate that no treatment except surgery will permanently resolve the signs. Many owners elect not to surgically treat their pet once they understand that the problem is self-limiting, that it almost never causes systemic illness, and that the signs, although likely to wax and wane throughout the dog’s life, are not life-threatening and may not be as serious or dangerous as the surgery required to correct the defect. Reluctance to perform surgery on these defects stems from the knowledge that the surgical area is not easily reached and that recurrence of a vaginal stricture is always possible. Splitting a pelvis, for example, is considered extremely aggressive, and if the surgeon believes that such an approach would be needed, thorough owner education is advised. Similarly, because the surgery is often in the location of the urethra, iatrogenic incontinence problems would be catastrophic.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree