Chapter 20 Use of Human Poison Centers in the Veterinary Setting

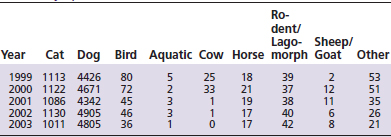

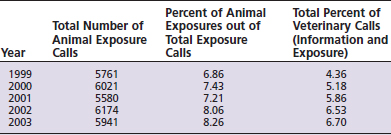

Each year poison centers receive an increasing number of veterinary calls. The majority of these are for exposures to household pets, especially dogs and cats (Table 20-1). From 1999 to 2003, the Washington Poison Center received an average of 5895 animal exposure calls per year.1 This represents an increase in overall animal exposures from 6.86% to 8.26% during that 5-year period.2 These numbers reflect actual exposures and do not include calls from owners, zoos, or veterinarians that were for poison information only (Table 20-2). Information calls relating to animals and requests for prevention materials from veterinary call sites and owners increased from 4.36% to 6.70% over the same period.2

ASSESSMENT AND EXPOSURE

The SPI must seek specific information concerning the exposure. Exact product identification, the estimated amount and concentration of the product involved, the time and route of the exposure, the species and weight of the animal, any signs the animal demonstrates, and any treatment already given are all obtained. Accurate identification of the product or medication involved is essential because of variations in formulations and the inherent toxicity of the ingredients. The specific product name, manufacturer, and ingredients need to be verified by the SPI and confirmed with the original product container, if available. This includes the strength or concentration of the medication or chemical and the form (solid, liquid, etc.) of the product. Tablets, liquids, solids, gases, and granules all pose different risks. Aerosol sprays pose an additional risk from the propellant, which can be more toxic than the active ingredient.

Medication toxicity is highly dependent on the species and weight of the animal and the specific dose of medication ingested. Cleaning products can vary from simple irritants to dangerous corrosives; even similarly named products by the same manufacturer can have many different ingredients and thus contrasting management guidelines. Soaps and detergents may be anionic or nonionic, representing little risk, or cationic, with the potential for greater harm.

It is important to determine if the product was diluted, and if so, how was it diluted? Dilution decreases the concentration or strength, and possibly the pH, of many toxins, making the exposure less harmful. A dog lapping full strength antifreeze from a spilled container is at more risk than a dog lapping diluted antifreeze that was then rinsed off the driveway and collected into a puddle. If the product was mixed with anything, it may be necessary to determine the toxicity of the additive as well.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree