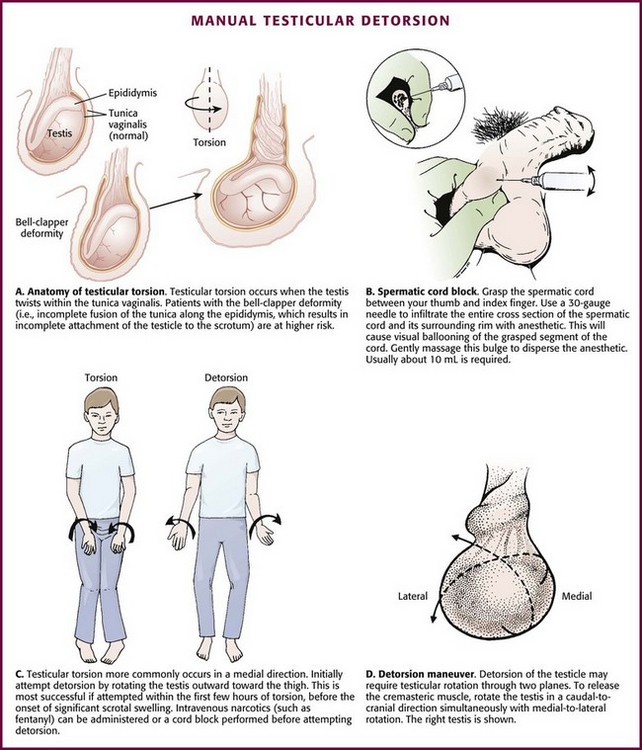

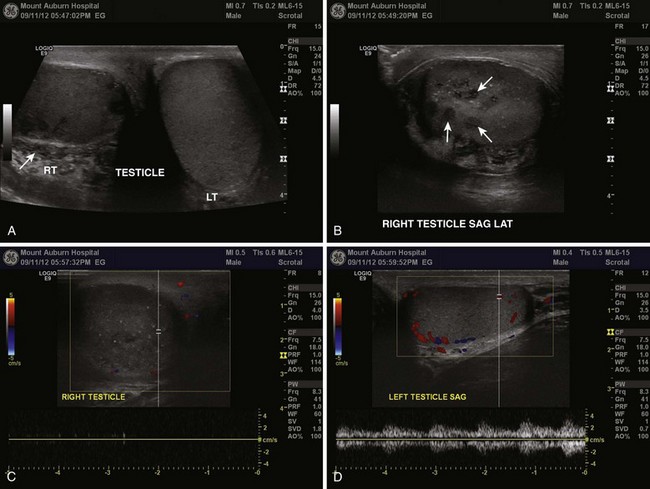

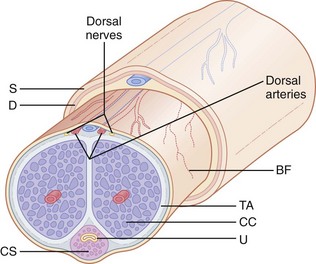

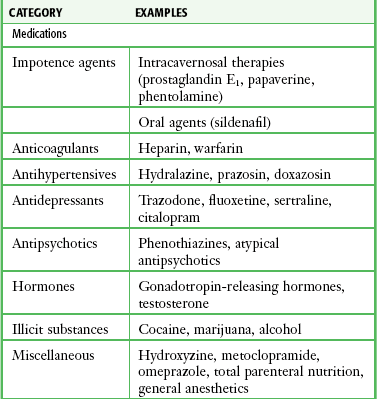

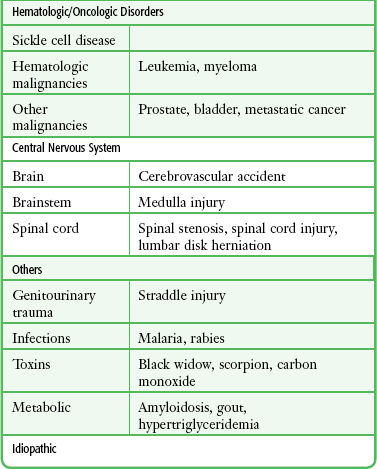

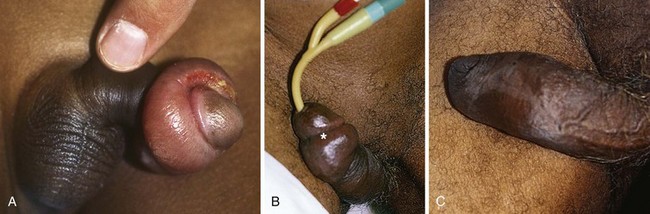

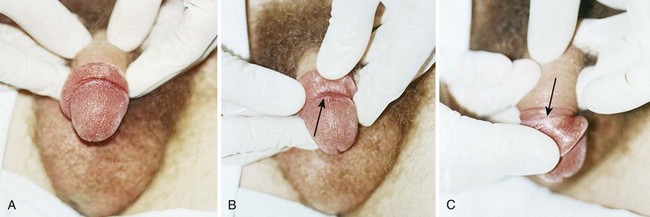

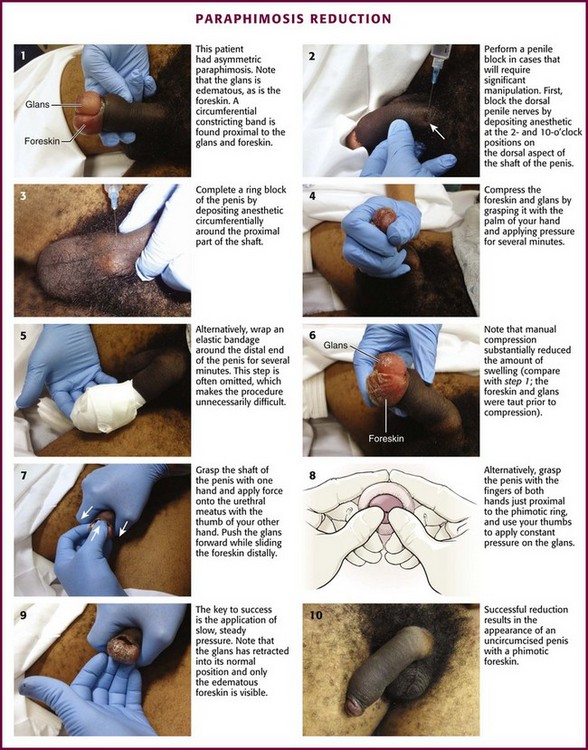

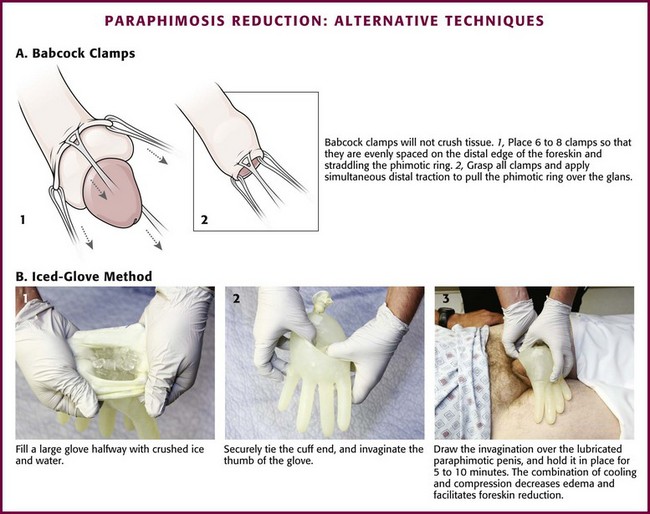

Chapter 55 Although acute scrotal pain accounts for less than 1% of overall emergency department (ED) visits, it may provoke great anxiety in the patient or caretaker given its highly sensitive nature.1 One of the most challenging aspects of scrotal complaints is that a wide variety of clinical conditions may have similar signs and symptoms: a male patient complaining of an acute, painful, swollen, and tender hemiscrotum. The most common urologic emergencies manifested as acute scrotal pain include testicular torsion, severe infectious epididymitis, and Fournier’s necrotizing fasciitis. Other painful conditions include torsion of the appendix testis, inguinal hernia, trauma, testicular cancer, referred pain (such as ureterolithiasis and diverticulitis), Henoch-Schönlein purpura, and orchitis (mumps, brucellosis, coxsackievirus disease, etc.). Hydrocele, varicocele, spermatocele, and testicular cancer tend to be characterized by painless, isolated swelling. Although the differential diagnosis is extensive, testicular torsion is the principal threat to fertility that needs to be ruled out. Definitive management of testicular torsion involves surgical exploration and orchiopexy. Manual detorsion, with or without spermatic cord anesthesia, can be attempted while simultaneously preparing for operative intervention. An acute scrotum is defined as an acute painful swelling of the scrotum or its contents, accompanied by local signs or general symptoms.2 Acute epididymitis is commonly the cause of acute scrotal pain in adolescents and adults. Torsion of testicular (or epididymal) appendages is another frequent cause of acute scrotal pain in prepubertal boys. A congenital anomaly of fixation of the testis, termed the bell-clapper deformity, is associated with the development of testicular torsion.3 It occurs when the intrascrotal portion of the spermatic cord lacks firm posterior adhesion to the scrotal wall and remains surrounded by the tunica vaginalis (Fig. 55-1A). As a result of the abnormal attachment, the testis may be suspended horizontally.4 These anatomic features predispose the affected testis to rotation. Testicular salvage rates decrease with time. A metaanalysis of 1140 patients in 22 series demonstrated a greater than 90% salvage rate when surgery was performed within 6 hours of the onset of pain. 5 Testicular atrophy may lead to decreased fertility. Furthermore, testicular loss may result in dysfunction of the contralateral testis through immune-mediated or other mechanisms.5 When used in the appropriate clinical setting, ultrasound remains the most useful diagnostic modality in the evaluation of genitourinary (GU) complaints (Fig. 55-2). A patient with compelling findings of testicular torsion on the history and physical examination does not require any preoperative diagnostic tests. Color flow Doppler ultrasonography (CDUS) may be very helpful in all other cases. The classic sonographic finding of testicular torsion is diminished intratesticular blood flow. In addition, examination of the spermatic cord with high-resolution gray-scale ultrasonography may reveal “coiling” or “kinking” of the cord at the site of torsion.6–8 Sonography is used not only to exclude testicular torsion but also to search for alternative causes of acute scrotal pain.9 With epididymitis, perfusion may be normal (or increased) because of the effects of inflammatory mediators on local vascular beds, although this is a nonspecific finding.10,11 An infarcted appendage may be visualized on ultrasound as well.12 Emergency physicians with appropriate training may be able to accurately assess intratesticular blood flow with bedside sonography in patients with acute scrotal pain.13 CDUS has long been regarded as the diagnostic modality of choice in assessing for testicular torsion. However, false-negative ultrasound results have been reported.14–20 Many of these studies are case reports or case series limited by small numbers and retrospective design. Two larger series reported documented intratesticular blood flow with CDUS in 6 of 23 (26%) and 50 of 208 cases (24%), respectively, of confirmed testicular torsion.6,21 Unfortunately, Doppler ultrasound may reveal seemingly adequate intratesticular blood flow in those with partial torsion, which can mislead the practitioner.22 Radionuclide scintigraphy and CDUS have similar sensitivity, as well as false-negative rates, for the diagnosis of testicular torsion.23 However, given the widespread availability of and expertise in ultrasound technology, combined with the risks associated with exposure to radioactive isotopes, radionuclide procedures have fallen out of favor. The use of magnetic resonance imaging has been explored, but limitations include speed of imaging and availability.24,25 Testicular torsion can be relieved by manual detorsion. A study of 162 cases of testicular torsion revealed that the anticipated lateral-to-medial rotation occurred in 67% of cases, with medial-to-lateral rotation seen in the remaining 33%.26 This challenges the standard dogma of medial-to-lateral rotation, or “opening the book,” as the standard method of detorsion. As noted, there may be a cranial-caudal component to the torsion as well. The end point of manual detorsion is relief of pain or return of intratesticular blood flow as seen on ultrasound imaging.27 Although manual detorsion may allow reperfusion of the testis, a lesser degree of residual torsion may remain. Given that infarction can occur with as little as 180 degrees of torsion, immediate surgical exploration is still advocated after what is thought to successful manual detorsion.26 The bottom line is that specialty consultation and plans for possible immediate surgical exploration need to occur regardless of the outcome of the detorsion procedure. Manual Detorsion and Spermatic Cord Anesthesia Spermatic Cord Anesthesia: Local anesthesia of the spermatic cord can be induced with 1% plain lidocaine injected at the external or superficial inguinal ring (Fig. 55-1B).28 First prepare the skin with an antiseptic solution. Grasp the cord between the thumb and index finger, and inject 10 mL of 1% plain lidocaine (in an adult) directly into the cord. If the cord is swollen, which is frequently the case with testicular torsion, or if the testicle is lying very high in the hemiscrotum because of spermatic cord torsion (thus precluding grasping), palpate the cord at the pubic tubercle as it passes over the pubis and inject the lidocaine at this landmark. Lee and colleagues29 were able to perform manual detorsion with local spermatic cord anesthesia in 70% of their cases of torsion in adults. Kresling and associates30 had success in 15 of 16 patients and noted a fair amount of associated cremasteric muscle spasm, which must also be relieved. Manual Detorsion: The goal of manual detorsion is to reestablish or increase blood flow to a previously ischemic testis. This should be done while the operating suite is being prepared. It should never delay operative intervention. Begin manual detorsion with the clinician standing comfortably at the side of the bed or stretcher, preferably on the patient’s right side if the clinician is right handed or on the left side if left handed. Begin detorsion just as one would open a book (i.e., an initial 180-degree detorsion of the patient’s right testis is done in a counterclockwise fashion) (see Fig. 55-1C and D). The patient’s left testis is detorsed 180 degrees in a clockwise fashion. Ask the patient whether there was any relief of pain after the maneuver. If one rotation relieves some but not all of the pain, continue with another rotation of the testis. The degree of torsion may range from 180 to 1080 degrees, with medians of 360 to 540 degrees.26 Many patients will require two or three rotations to fully alleviate their pain. If the initial detorsion is mechanically difficult (which it will be if detorsion is done in the wrong direction) or makes the pain worse, detorse the testis in the opposite direction and observe the result. Approximately one third of testicular torsions occur in the lateral, or unexpected, direction.26 The objective success or failure of testicular manipulation can be further substantiated by an increase in Doppler signal and symptomatic relief of pain. Priapism is defined as a prolonged erection of the penis, generally for more than 4 hours, in the absence of sexual desire or stimulation (Fig. 55-3). This medical condition was named after Priapus, an ancient Greek god of fertility and horticulture who was endowed with oversized genitalia.31 Ischemic priapism can be thought of as a compartment syndrome of the penis.32 The corpora cavernosa become engorged with stagnant, oxygen-depleted venous blood because of either intraluminal obstruction of venous blood flow or an inability of the penile muscle tissue to adequately contract and augment venous outflow.33 More than a third of patients with severe priapism may suffer permanent erectile dysfunction despite treatment, with obvious functional and emotional sequelae.33 Priapism is characterized clinically by a soft glans penis and spongy urethra in the presence of two erect penile bodies (corpora cavernosa) (Fig. 55-4). Two important concepts are worthy of mention. First, there is communication of blood flow between the corpora cavernosa; therefore, in most cases the operator needs to access only one of the corpora. Second, the introduction of vasoactive or other agents into the corpora is akin to an intravenous injection and may precipitate systemic effects, particularly when partial detumescence is achieved. In the past, priapism was most often encountered as a complication of a number of medical conditions, such as hematologic, neoplastic, or drug-related conditions. Today, many cases are iatrogenic and result from the current practice of using vasoactive substances (e.g., papaverine and phentolamine). Another cause is the newer erectile dysfunction medications used to induce penile erections in impotent men. Sickle cell disease continues to be a leading cause of priapism. Sickle cell patients may experience such a high rate of recurrence that home self-injection of vasoactive drugs into the penis has been advocated. Cocaine use is one cause that is likely to be underreported.34 A drug screen may unravel some discrepancies between the clinical findings and history. As an end result, vasoactive drugs promote engorgement of the corpora cavernosa and reduction in venous outflow, which may result in low-flow or ischemic priapism.35–37 Several phosphodiesterase inhibitors and prostaglandin E1 are the drug treatments of impotence approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. These medications act by increasing penile blood flow by enhancing smooth muscle relaxation. The incidence of priapism with these medications is quite low, particularly with the phosphodiesterase inhibitors. Penile rigidity secondary to a nondeflating penile prosthesis (pseudopriapism) or malignant replacement of the corpora in patients with bladder or prostate cancer should not be confused with true priapism. Selected causes of ischemic priapism are listed in Table 55-1. Attempt to identify reversible causes of low-flow priapism and initiate specific corrective therapy as soon as possible. Low-flow priapism in children and young adults may be due to sickle cell disease, and such cases may respond to noninvasive standard antisickling measures. However, the role of transfusion therapy in patients with priapism caused by sickle cell anemia is uncertain.38 Treatment of ischemic priapism is frequently initiated in the ED. The classic teaching is that the initial treatment—oral or subcutaneous terbutaline—is the same regardless of the cause, but its utility is debated.39–41 It is thought that terbutaline, a β2-adrenergic agonist, increases venous outflow from the engorged corpora by relaxing venous sinusoidal smooth muscle. Terbutaline is of unproven benefit and is often ineffective; however, given its limited propensity for adverse effects, it is reasonable to initiate a trial in selected circumstances.42 A subtype of ischemic priapism is known as stuttering priapism. This entity is typically observed in patients with sickle cell disease. Patients experience recurrent episodes of priapism that often last less than 3 hours and frequently do not require emergency treatment unless the symptoms become markedly prolonged.43 High-flow (non-ischemic) priapism is treated surgically (nonurgent). Although perhaps intuitive treatment, transfusion therapy for acute priapism of sickle cell disease is controversial. Exchange transfusion has been associated with acute neurological events (headache, seizures, obtundation) that are thought to be due to a rapid elevation of hemoglobin (greater than 12 g/dL) and a release of procoagulant and vasoactive factors from the corpus carvernosa (ASPEN syndrome). Partial exchange transfusion (target hemoglobin less than 10 g/dL) has not been associated with these condition. A suggested algorithm for the initial treatment of acute nonischemic priapism in the emergency setting is presented in Box 55-1. Relief of priapism by simple injection of vasoactive solutions into the corpus cavernosum is a procedure that has been reported.44 Intercavernous injection therapy for the management of priapism is simple to perform, less traumatic, and less invasive than aspiration and irrigation. This minimally invasive procedure may be attempted as an initial approach. The same procedure may be used as a self-injection technique for home treatment of recurrent priapism. With this technique, a 25- to 27-gauge needle (tuberculin or insulin syringe) is used to inject vasoactive substances into the corpus at the proximal end of the penis (2 to 4 cm distal to the origin of the shaft), with the goal of pharmacologically reversing the priapism (Fig. 55-5A). The principle is sympathomimetic-initiated contraction of the cavernous smooth muscle to permit venous outflow. Frequently, this small needle injection can be accomplished without anesthesia and is usually barely perceived by the patient. The most recommended technique is to inject 0.2 to 0.5 mg of phenylephrine into the corpus every 10 to 15 minutes to a maximum of four to five doses, although more frequent dosing has also been advocated. Use the lower dose in patients with cardiovascular pathology. Phenylephrine is available as a 1% solution (10 mg/mL), which must be diluted for this procedure. If 1 mL (10 mg) of the 1% solution of phenylephrine is added to 9 mL of saline, the final phenylephrine concentration is 1 mg/mL. Then withdraw 0.2 mL (0.2 mg) or 0.5 mL (0.5 mg) of this diluted solution with a tuberculin or insulin syringe and add saline to increase the final volume for injection to 1 mL. Phenylephrine is preferred by the American Urologic Society because of minimal cardiovascular side effects. An alternative, readily available injection solution is a mixture of epinephrine and saline. Draw up 0.1 mg of epinephrine (0.1 mL of 1 : 1000) in a tuberculin or insulin syringe and dilute it with 0.9 mL of saline (total volume of 1 mL). Systemic effects, such as hypertension, headache, tremors, and cardiac arrhythmias, are potential side effects of any sympathomimetic injection, so caution is advised, especially if multiple injections are used in a semi-erectile state. Puncture the corpus with the needle at the 10- or 2-o’clock position at the base of the penis (with 12 o’clock being the dorsal vein of the penis). Aspirate blood to confirm the correct position, and then inject the solution. If not successful in 20 to 30 minutes, repeat the injection up to a total of three injections. In one small study, successful detumescence was achieved in eight of nine patients by simple intracorporal injection of phenylephrine via this regimen, and three or fewer injections were required.45 Only one side needs to be injected. Two or three injections might be necessary. Wait at least 20 minutes after each injection before trying additional interventions. Note that this is essentially an intravenous injection and systemic effects may occur, especially if partial detumescence has been achieved. Accordingly, proceed with caution in patients with cardiovascular disease. Success has also been noted by injecting the corpus cavernosum with 1 mL of the local anesthetic lidocaine (2%) with epinephrine (1 : 100,000) into each side or 2 mL into one side.44 Table 55-2 lists adrenergic agents used for intracavernosal injections. Table 55-2 Adrenergic Agents Used for Intracavernous Injections *Single side injected with the entire amount. See text for preparation of the phenylephrine injection solution. †Total amount divided into two doses. Inject each side with half the total volume (1 mL) or inject the total volume (2 mL) into one side. From Roberts JR, Price C, Mazzeo T. Intracavernous epinephrine: a minimally invasive treatment for priapism in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2009;36:3:285-289. If injection is unsuccessful or if the erection has persisted for more than 4 to 6 hours, aspiration of blood from the corpus cavernosum, with or without irrigation, is performed. This is usually combined with an intracavernosal injection of a sympathomimetic drug. Box 55-2 lists the equipment needed for aspiration and irrigation of the corpus cavernosum. This procedure entails drainage of blood from the erect penis, irrigation with saline if necessary (i.e., inadequate return of blood with lack of detumescence), and finally, instillation of a vasoactive medication. As an alternative to instillation of a sympathomimetic drug, irrigation with aliquots of a dilute vasoactive solution (1 mg of epinephrine added to 1 L of saline) may be effective (aspirate-infuse-aspirate cycle as needed). Place the patient in the supine position. Use parenteral analgesia and sedation. Local anesthesia is recommended and may be achieved with a generous local wheal of lidocaine injected at the puncture site but is best obtained with a penile nerve block (Fig. 55-5B, step 2). Perform the block by injecting 1% plain lidocaine at the base of the dorsal and ventral surface of the penis for a dorsal penile nerve block, or place a circumferential penile block. The nerves are relatively superficial and deep injections are not required. Prepare and drape the penis in sterile fashion. Grasp the shaft of the penis with the nondominant thumb and index finger. Palpate the engorged corpus cavernosum laterally (2- and 10-o’clock positions), and insert a 19-gauge butterfly needle into the corpus cavernosum (see Fig. 55-5B, step 3).46 A dialysis access butterfly needle may also be used (Fig. 55-6). Small butterfly needles and standard intravenous catheters are not ideally suited for the procedure but may be used. If palpation fails to identify the corpus, blindly insert the needle at either 10 or 2 o’clock to gain access to this large vascular structure. Because there is communication of blood flow between both sides, only one of the corpora needs to be aspirated or irrigated. Either side may be punctured. The site of needle placement is typically anywhere from the base to the proximal end of the shaft, approximately 2 to 4 cm distal to its origin. Do not use the glans as a puncture site. If detumescence is achieved and maintained after initial aspiration, no further treatment may be necessary. Even if this is successful, some advise instilling an aliquot of a vasoactive substance. Phenylephrine is recommended as the agent of choice because it may minimize the risk for cardiovascular side effects that are caused by the more common sympathomimetic agents.41 Inject 0.2 to 0.5 mg of phenylephrine (diluted in 1 mL of normal saline). The concentration recommended for instillation is similar to that suggested for the minimally invasive technique detailed earlier. Use lower concentrations in smaller volumes for patients with cardiovascular risk factors or for children. If irrigation has been performed with a dilute vasoactive substance as delineated below, additional instillation of medication is not suggested. Observe the patient in the ED for recurrence. Although the ideal observation period is unknown, 2 hours has been suggested.44 Figure 55-5B, step 4, demonstrates the entire penis loosely wrapped with an elastic (Ace) bandage to prevent hematoma formation at the injection site or sites. Provide strict return precautions for recurrence of priapism, and ensure that urgent urology follow-up is possible. A short course of an oral α-adrenergic agent, such as pseudoephedrine for 3 days, is often recommended.44 However, this intervention is of questionable value and unproven benefit. Although hematoma and infection can occur after properly performed aspiration, these complications are infrequent. Injected or instilled vasoactive agents can be absorbed systemically, with potential toxic effects.47 Therefore, the intracavernosal use of vasoactive agents is relatively contraindicated in patients with conditions that are sensitive to these agents (e.g., severe hypertension, dysrhythmias, monoamine oxidase inhibitor use). Monitor blood pressure and cardiac rhythm throughout the procedure if the patient is at risk. Failure to aspirate blood is a potential complication, usually because of a misplaced needle, application of excessive suction, or clotted blood. Because impotence is a well-recognized complication of priapism regardless of the cause or promptness of therapeutic intervention, advise the patient regarding this potential complication. Because prolonged priapism increases the risk for subsequent erectile dysfunction, an aggressive management strategy is advised. After 4 hours of persistent priapism there is heightened release of inflammatory cytokines in the acidotic and hypoxic corpora cavernosa. Inflammation may result in changes in smooth muscle, including cell death and fibrosis, which may cause permanent erectile dysfunction.48 Recurrence is not uncommon, and some patients require multiple procedures on a recurring basis. Surgical shunting procedures might be required if these other measures are not met with success. Paraphimosis may occur at any age but is often seen in the extremes of life (Fig. 55-7). The condition can be quite subtle and may be either unrecognized or misdiagnosed as an allergic reaction, penile trauma, infection, or edema resulting from systemic volume overload (i.e., congestive heart failure, nephrotic syndrome) (Fig. 55-8). Paraphimosis is a urologic emergency that must be treated promptly to prevent necrosis of the glans. It can frequently be managed in the ED without the need for emergency specialty consultation. Many methods for successful reduction of paraphimosis have been reported; however, the most commonly used initial maneuver involves manual compression of the distal end of the glans penis to decrease edema, followed by reduction of the glans penis back through the proximal constricting band of foreskin.49 The penis consists of the paired corpora cavernosa, or erectile bodies, which lie dorsal to the corpus spongiosum (see Fig. 55-4). The corpus spongiosum surrounds the penile urethra. The corpora cavernosa and the corpus spongiosum are wrapped in a thin connective tissue layer called the tunica albuginea. The glans is the distal head of the penis. The distal foreskin, or prepuce, in uncircumcised males lies over the glans and can be retracted proximally to expose the glans. The coronal sulcus distinguishes the glans penis from the penile shaft (see Figs. 55-7B and 55-8B). Patients will have a red, painful, and swollen glans penis associated with an edematous, proximally retracted foreskin that forms a circumferential constricting band. The normal anatomy and identification of the foreskin may be obfuscated by edema, and the condition can be asymmetric and rather bizarre appearing (Fig. 55-9, step 1). The penile shaft proximal to the constricting band is typically soft. The entrapped foreskin forms a constricting band on the penile shaft. Compression inhibits venous drainage of the glans, sulcus, and distal part of the foreskin itself and results in a vicious circle of progressive glans and foreskin edema that may further prevent reduction of the foreskin to its natural position. The edema may become so severe that arterial flow is compromised, which can result in necrosis and gangrene of the glans penis. Emergency reduction of a paraphimotic foreskin is indicated whenever the condition exists. The current standard for reducing paraphimosis is manual reduction. It can be facilitated by applying a nonirritating topical anesthetic lubricant onto the inner surface of the foreskin (not the shaft of the penis) and the glans to reduce friction and decrease the discomfort of the procedure. A dorsal and ventral penile block should be performed in cases that require significant manipulation (see Fig. 55-9, steps 2 and 3). If significant discomfort or patient apprehension is present, systemic analgesia or procedural sedation may be useful adjuncts. For young children, general anesthesia may be necessary.50 Compress the foreskin and glans by snugly grasping it with the palm of the hand and apply pressure for several minutes, or wrap an elastic bandage around the distal end of the penis to reduce as much edema fluid as possible (see Fig. 55-9, steps 4 and 5).51 Compression is often omitted and makes the procedure more difficult. A significant amount of edema can be alleviated with simple compression (see Fig. 55-9, step 6). Place the index and long fingers of both hands in apposition just proximal to the phimotic ring. Align both thumbs on the urethral meatus and apply constant force. Use the thumbs to invert the glans penis proximally, and use the index and long fingers to attempt to reduce the phimotic ring distally over the glans penis into its normal anatomic position (see Fig. 55-9, step 8). Successful reduction results in the appearance of an uncircumcised penis with a phimotic foreskin (see Fig. 55-9, steps 9 and 10). Alternatively, use the thumb to push the glans through the foreskin that is encircled by the entire palm (see Fig. 55-9, step 7). The key to success in both these maneuvers is the application of slow, steady pressure. Use Babcock clamps (noncrushing tissue clamps) to reduce the paraphimotic foreskin (Fig. 55-10A).52 Apply six to eight Babcock clamps spaced evenly around the foreskin and straddling the phimotic ring (one edge just proximal and the other edge just distal to the phimotic ring). Grasp all the clamps and apply simultaneous distal traction to pull the phimotic ring over the glans. After reduction, remove the clamps. It is important to inspect the foreskin afterward for injury. Other techniques focus on reduction of glans or foreskin edema (or both), followed by reduction of the paraphimosis. Diminished glans edema may allow the edematous foreskin to be reduced distally to its natural position. A suggested maneuver involves the application of an ice pack. In the “iced-glove” method, cold compression is used to reduce foreskin swelling and induce vasoconstriction in the glans penis (see. Fig. 55-10B).53 Fill a large glove halfway with crushed ice and water, and tie the cuff end securely. Invaginate the thumb of the glove and then draw it over the lubricated paraphimotic penis. Hold the thumb of the glove securely in place over the glans for 5 to 10 minutes. The combination of cooling and compression usually decreases the edema sufficiently to permit manual reduction of the foreskin. Wrapping the glans (and penis) in a compressive bandage is another option.51 Alternatively, techniques focusing on reduction of foreskin edema have been advocated (Box 55-3). Though not usually pursued in the ED, they will be included for completeness. The Dundee technique involves making multiple micropunctures in the edematous foreskin and then squeezing out the edema fluid.54 Hyaluronidase has been reported to result in rapid reduction of prepuce edema to facilitate manual reduction of the foreskin. This enzyme, when injected into the swollen retracted foreskin, causes hydrolysis of hyaluronic acid, which in turn increases tissue permeability so that the edema in the foreskin is diffused out into the surrounding tissue of the penis.55 There have even been advocates of a noninvasive way to reduce the foreskin edema via the application of granulated sugar to the penis. Sugar forms an osmotic gradient that draws out the fluid with reduction of the edema, but this may take several hours.56 Publications on these alternative procedures are generally observational in design with very small numbers. To date, there have not been any large studies of comparative effectiveness; consequently, it is difficult to recommend any one method as being superior to the others.57

Urologic Procedures

Testicular Torsion

Background

Anatomy and Physiology

Pathophysiology

Indications

Procedure

Priapism

Background

Anatomy and Physiology

Pathophysiology

Indications

Contraindications

Procedure

Minimally Invasive Technique—Simple Injection

AGENT

DOSE

VOLUME

Phenylephrine*

0.2-0.5 mg

Dilute with saline; final volume, 1 mL*

Epinephrine (1 : 1000)

0.1 mg (0.1 mL)

Dilute with 0.9 mL saline; final volume, 1 mL

Lidocaine (2%) with epinephrine (1 : 100,000) (local anesthetic solution)

40 mg lidocaine

0.02 mg epinephrine (2 mL)

1 mL injected into each side of the corpus cavernosum; final volume, 2 mL†

Aspiration/Irrigation Technique

Aftercare

Complications

Conclusion

Paraphimosis

Background

Anatomy and Physiology

Pathophysiology

Indications

Procedure

Adjunctive Techniques to Assist in Manual Reduction