CHAPTER 9 Urinary Tract Infections

ETIOLOGY

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is caused by microbial colonization of the kidney, ureter, urine, or proximal urethra. The incidence of UTIs in the horse is low.1–5 UTIs can be divided anatomically into upper UTI, involving the kidney and ureters, and lower UTI, involving the bladder and urethra. Ascending infections are the most common method of bacterial colonization, with the exception of septicemia-associated nephritis in neonatal foals.6 Upper UTIs occur less frequently and can occasionally be life threatening.4 Lower UTI is generally caused by abnormal urine flow. Urolithiasis and partial obstruction are often the cause of both upper and lower UTI in horses.

The most frequently reported bacteria in UTI include Escherichia coli, Proteus, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.7 Gram-positive infections in horses are less common, but Staphylococcus and Corynebacterium spp. have been isolated.8 Enterococcus spp. have been identified in horses with abnormal urine flow or horses that were instrumented with a urinary catheter. Isolation of more than one organism from the urine is common. Neonatal foals receiving broad-spectrum antimicrobials can develop Candida infections in the lower urinary tract.4

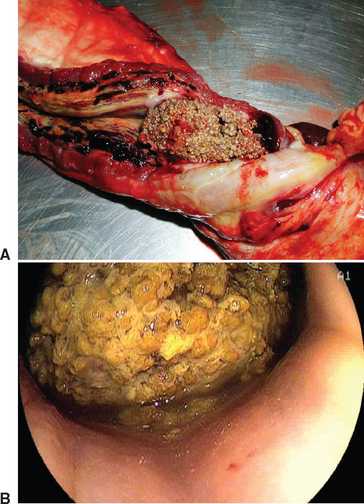

The most frequent causes of UTI in the horse are bladder paralysis (Fig. 9-1), urolithiasis (Fig. 9-2), and trauma to the urethra.4 Urethritis can result from urethral damage in geldings and stallions secondary to neoplasia, habronemiasis, or trauma to the penis or sheath.9,10 Any alteration or obstruction to urine flow can predispose to infection. Mares are more likely to develop UTI than male horses because of their shorter urethra and the potential for fecal contamination from poor perineal conformation. In addition, mares may sustain damage to the urethra from trauma associated with foaling.

Cystitis may occur secondary to bladder paralysis, bladder neoplasia, or urolithiasis. Neurologic disease, such as equine protozoal myeloencephalitis or equine herpesvirus type 1 (EHV-1), and trauma can result in bladder paralysis. Consumption of Sudan grass and Johnson grass has resulted in ataxia and urinary incontinence in the southwestern United States from sublethal intoxication with hydrocyanic acid in the plants.7,11,12 Conditions that inhibit bladder emptying at regular intervals encourage the growth of bacteria. Urolithiasis in the bladder can damage the mucosa lining, destroying normal defense mechanisms against microbial colonization. Obstruction of the renal pelvis, ureter, or urethra with urinary calculi may result in UTI. Unlike small animal patients, horses rarely develop UTI secondary to urinary catheterization, with the exception of sick neonatal foals.12,13

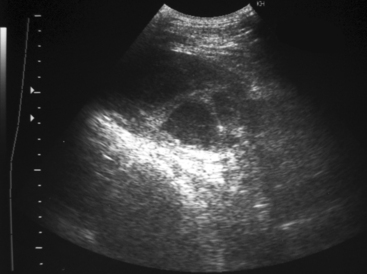

Pyelonephritis is rare in horses2–4 (Fig. 9-3). The ureters attach dorsally on the bladder, providing a physical barrier to vesicoureteral reflux, which is responsible for ascending infection. Problems that disrupt this normal barrier include ectopic ureter, enlargement of the bladder from paralysis, or obstruction of urine flow from urolithiasis.12

PATHOGENESIS

UTIs are the result of pathogenic bacteria colonizing the urethra and then migrating to the bladder, where they multiply.12,14 Fecal bacteria can adhere to the uroepithelial cells of the urethra when normal flora is altered by turbulent urine flow.15 After the pathogenic bacteria colonize in the distal urethra, they must rapidly reproduce between micturition to migrate through the proximal urethra and bladder, which do not have protective flora.

Bacterial virulence properties and host defense mechanisms play a role in the development of UTIs. For example, pathogenic Escherichia coli has surface adhesins that can bind to specific glycolipid receptors on uroepithelial cells.12 Host defense mechanisms include normal flora, normal anatomy, and normal micturition. An intact mucosal defense system includes glycosaminoglycan coating of uroepithelial cells and immunoglobulins in the urine.15–17 Normal flora of the UTI can be protective against pathogenic bacteria unless urine flow or an anatomic defect compromises the environment. It has been hypothesized that women with recurrent UTI have decreased immunoglobulin A in their urine.18 Glycosaminoglycan can coat the uroepithelium, providing a barrier for bacterial attachment. If this layer is damaged by uroliths or neoplastic cells, infections are more likely to occur. Glycosaminoglycan production is directly influenced by estrogen. Prepubertal and postmenopausal women are at an increased risk of UTI because of a decrease in estrogen.19 Currently, there is no evidence to support an increased risk of UTI in fillies or pregnant mares.

Upper UTI in the horse is uncommon. Infection of the ureter and kidney can occur with compromise of the protective valve, which inhibits vesicoureteral reflux secondary to ectopic ureter, bladder distention, or urethral obstruction. These conditions lead to dilated ureters and vesicoureteral reflux with contaminated urine. The renal cortex is much more resistant to bacterial infection than the renal medulla, decreasing the possibility of hematogenous spread.15

CLINICAL FINDINGS

Clinical signs of lower UTI may include dysuria, pollakiuria, stranguria, and incontinence. Urine scalding on the perineum in mares or on the dorsal aspect of the hindlimbs in geldings or stallions may indicate chronic UTI (Fig. 9-4). Hematuria occurs with disruption of the mucosal lining associated with accumulation of sabulous urine sediment or urolithiasis. If hematuria is present only at the end of urination, this suggests that the origin of the problem is the bladder or proximal urethra. If a urolith completely obstructs urine flow, colic may be the presenting complaint.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree