36 Urinary tract emergencies

Urethral Obstruction

Feline

Theory refresher

Clinical Tip

Prolonged urethral obstruction results in hypovolaemia and systemic hypoperfusion that may occur for a number of reasons, including the effect of hyperkalaenia and acidaemia on the cardiovascular system, and dehydration where this is a factor. In addition to azotaemia, urethral obstruction can result in profound electrolyte and acid–base disturbances including metabolic acidosis, hyperphosphataemia and hypocalcaemia. Hyperkalaemia occurs mainly due to impaired urinary excretion of potassium. The clinical manifestations of hyperkalaemia reflect alterations in cell membrane excitability and of greatest concern are the potentially life-threatening effects on cardiac conduction (Box 36.1).

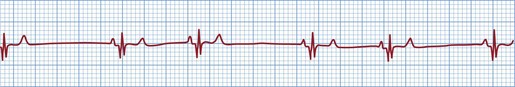

BOX 36.1 Electrocardiographic findings associated with hyperkalaemia

Figure 36.2 Atrial standstill in a cat with hyperkalaemia showing absence of P waves; peaked T waves are also present.

(From Darke PGG, Bonagura JD, Kelly DK 1996 Color atlas of veterinary cardiology. Mosby-Wolfe, London, with permission.)

Clinical Tip

Table 36.1 Treatment of clinically significant hyperkalaemia

| Agent | Dose/route | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| 10% calcium gluconate | 0.5–1.0 ml/kg i.v. bolus over 30–60 s | |

| Neutral (regular, soluble) insulin | 0.1–0.5 IU/kg i.v. | Slower onset of action (can be more than 15 minutes) |

| Glucose solution | 0.25–0.5 g/kg i.v. | |

| Sodium bicarbonate | 1–2 mmol/kg slow i.v. (repeat if necessary) |

ECG, electrocardiogram; IU, international units; i.v., intravenous.

Case example 1

Emergency database

Clinical Tip

Case management

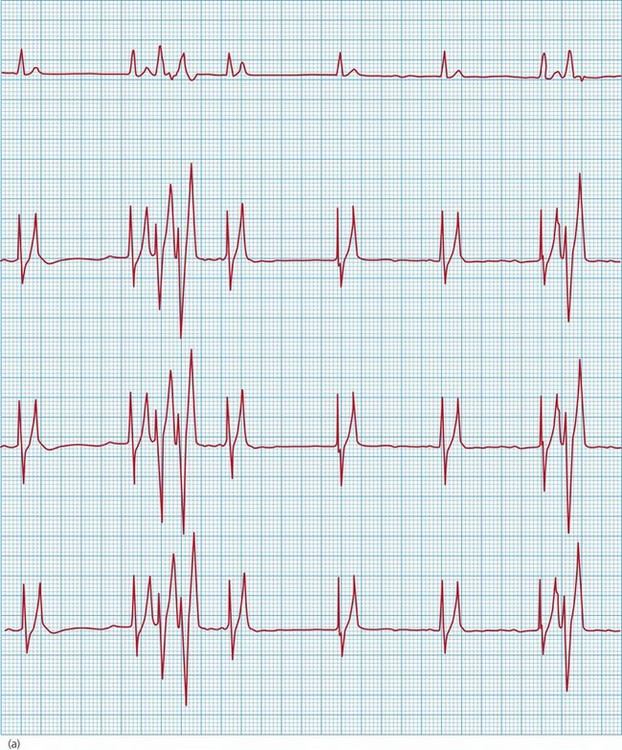

The cat was started on a 20 ml/kg bolus of 0.9% sodium chloride (normal, physiological saline) and treated immediately thereafter with 10% calcium gluconate (see Table 36.1) to which there was a rapid response with respect to heart rate and rhythm (see Figure 36.3). Neutral (regular, soluble) insulin and glucose were administered intravenously at this time. No warming measures were performed initially in order not to worsen hypoperfusion (see Ch. 17) but the cat was given a low dose of methadone (0.1 mg/kg i.v.). Another dose of calcium gluconate was also given, prompted by deterioration of the heart rhythm.

Clinical Tip

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree