Chapter 10 Urinary Tract Diseases

ABNORMAL URINARY CONSTITUENTS AND CONDITIONS

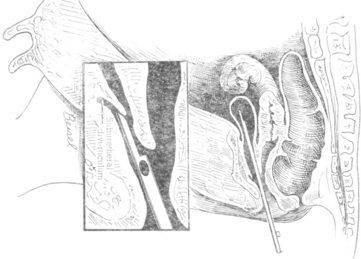

Urinary tract diseases are less common in dairy cattle than disorders of the gastrointestinal, respiratory, musculoskeletal, and other systems. For this reason and because signs of renal disease may be subtle, the urinary tract often is overlooked as a cause of illness. Evaluation of urine for abnormal constituents, urinalysis, and serum chemistry may be necessary to confirm urinary tract disease. Additionally, ultrasound examination of the kidneys and/or cystoscopic examination may be warranted in some cases. Percutaneous examination of both kidneys can be achieved easily in adult dairy cows and calves through the paralumbar fossae with a 2.5- to 5-mHz probe, and excellent images of the left kidney, ureter, and bladder can often be obtained during rectal examination using a conventional 5- or 10-mHz reproductive probe. Geographic differences in the incidence of diseases also may affect the relative frequency of urinary tract disease in cattle. Most practitioners utilize the gross appearance of urine, evaluation of abnormal urine constituents based on multiple reagent test strips, and signs found on physical examination as indicators of urinary tract disease. Vague illnesses that originate from the urinary system may require more ancillary data in the form of complete urinalysis, serum electrolytes and chemistry, and complete blood counts (CBCs) for diagnosis. Fortunately urine is obtained routinely during completion of physical examination for evaluation of urinary ketones, and this provides a sample for other routine screening processes when indicated. Abnormal urinary constituents identified by multiple reagent strips seldom are specific but give direction as to other ancillary tests to be performed. The following discussion of abnormal urinary constituents will give examples of diseases to be considered in a differential diagnosis. Although midstream samples are usually sufficient for cultures, on rare occasion it may be necessary to collect a catheterized sample. Catheterization is difficult in the cow because of the urethral diverticulum, and the technique is shown in Figure 10-1.

Proteinuria

Proteinuria may be normal in ruminants less than 2 days of age that have ingested adequate or large amounts of colostrum. This physiologic phenomenon should correct quickly after this time, and the urine should then be negative for protein. Any insult to the renal glomeruli or tubules could lead to mild or moderate proteinuria. For example, renal infarcts secondary to severe dehydration and reduced renal perfusion could cause mild proteinuria, whereas glomerulonephritis, tubular nephrosis, amyloidosis, pyelonephritis, and other severe renal diseases would lead to more significant proteinuria with eventual hypoalbuminemia. Nonspecific inflammation or irritation of the postrenal urinary tract as found in cystitis, urolithiasis, trauma, or neoplasia also may result in proteinuria. Finally, false-positive proteinuria may occur from admixture of urine with vaginal discharges, preputial discharges, uterine discharges, or fecal material and is therefore particularly common in free-catch samples obtained from normal, healthy postparturient cattle.

White Blood Cells

Microscopic evidence of white blood cells (WBCs) merely provides evidence of urinary tract inflammation or degeneration. The most common causes include renal inflammation or degeneration, ureteral infection or obstruction, and cystitis. Contamination of free-catch samples by normal lochia or abnormal uterine/vaginal discharges is common in postpartum cows. The finding of 1 to 5 WBCs per high power field should be considered normal in urine samples obtained from cattle. Tubular degeneration caused by nephrosis or nephritis must be differentiated from lower urinary tract infection or inflammation. Gross pyuria is observed most commonly in pyelonephritis or cystitis in cattle. Urine samples demonstrated to have gross or microscopic pyuria should be submitted for bacterial culture; ideally such samples should be obtained following aseptic preparation and bladder catheterization.

RENAL DISEASES

Embolic Nephritis

This condition occurs in septicemic calves and cows or occasionally in endocarditis patients with left-sided valvular disease (Figure 10-2). Fever, other signs of septicemia, and specific organ dysfunction (e.g., mastitis, joint infections) also may be present. Urine multiple reagent test strips may be positive for blood and protein, whereas microscopic examination of the urine will reveal increased numbers of WBCs, RBCs, and bacteria in some cases. Nephritis is seldom the most significant component of disease in these animals but is another sign of septicemia. Therapy must be directed against the primary disease.

Toxic Nephrosis

Damage to the renal tubules by toxins, certain drugs, and physiologic events linked to hemoconcentration, endotoxemia, and ischemic changes may cause tubular degeneration, inflammation, and in some instances interstitial nephritis. Usually both kidneys are affected equally.

Etiology

Clinical Pathology and Diagnosis

The diagnosis is linked primarily to clinical pathology data and history. Renal failure will be documented by a urine specific gravity in the isosthenuric range (,1.022) despite obvious dehydration. RBCs, WBCs, granular casts, and proteinuria usually are confirmed by urinalysis in acute nephrosis. Azotemia is present and characterized by elevations of serum urea nitrogen and creatinine. Specific causes may be suggested by the history (i.e., previous use of aminoglycosides, NSAIDs) or merely suspected (severe dehydration in a patient with salmonellosis). Serum chemistry often confirms hypochloremia, which may be more severe than that seen with intestinal obstruction, hypokalemia, hyponatremia, hypocalcemia, hyperphosphatemia, and hypermagnesemia.

Ultrasound study of the kidney may be a helpful ancillary procedure if available.

Pyelonephritis

Etiology

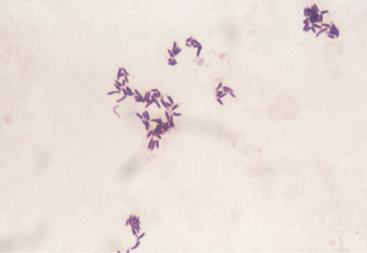

In cattle, bacterial pyelonephritis has been attributed to ascending infection of the urinary tract by Escherichia coli or Corynebacterium renale (Figure 10-3). At least three C. renale serotypes exist as normal flora of the caudal portion of the reproductive tract of female cattle and the sheath of male cattle. Unlike most gram-positive organisms, C. renale possesses pili that promote attachment to and colonization of the urinary tract mucosa. Conditions that provide physical or chemical damage to the mucosa in the lower portion of the urinary tract such as dystocia, bladder paralysis, or catheterization may predispose the cow to pyelonephritis as a result of C. renale ascending infection from the urinary bladder to the ureters and kidneys. C. renale causes a humoral antibody response when renal infection develops but not when infection is limited to the bladder. Because routine catheterization of cattle to assess urinary ketones has been abandoned, pyelonephritis caused by C. renale is seen less frequently, whereas pyelonephritis caused by gram-negative organisms is seen more frequently. Pyelonephritis as a result of E. coli infection has a similar pathogenesis to pyelonephritis caused by C. renale in that ascending infection from the lower urinary tract occurs following damage to the caudal portion of the reproductive tract.

Clinical Signs

Acute primary pyelonephritis causes fever of 103.5 to 105.5° F (39.72 to 40.83° C), anorexia, and a precipitous decrease in milk production. Some cows with acute pyelonephritis have colic manifested by kicking at the abdomen, restlessness, and treading. Signs of colic usually are associated with renal or ureteral inflammation and pain, but urinary obstruction caused by blood clots blocking urine outflow from a kidney (ureter) or bladder (urethral) also may contribute to colic (Figure 10-4). Further agitation, such as swishing of the tail, may be observed if the affected cow also has cystitis as a precursor lesion of pyelonephritis. Stranguria, polyuria, an arched stance, gross hematuria (Figures 10-4 and 10-5), blood clots, fibrin, or pyuria also are observed in some patients with C. renale infection. Acute pyelonephritis should be considered as a differential for acute colic in postparturient cattle. Consequently left kidney and ureter palpation per rectum should be mandatory components of the physical examination of any sick cow with signs of colic.

Chronic pyelonephritis is associated with weight loss, poor hair coat, anorexia, poor production, diarrhea, polyuria, anemia, stranguria and gross urine abnormalities. Lordosis and stretching out may be apparent in some cows affected with chronic pyelonephritis because of renal pain.

Diagnosis

Azotemia is cause for prognostic concern and may indicate prerenal conditions such as dehydration, bilateral pyelonephritis with subsequent renal failure, or postrenal urinary obstruction. Postrenal obstruction usually is obvious following the physical examination and rectal examination. Prerenal azotemia should be suspected if the animal is very dehydrated but is capable of concentrating urine to a specific gravity .1.022. Prerenal azotemia also should respond to rehydration using oral or IV fluids. Most cattle with pyelonephritis that also are azotemic have bilateral disease and renal failure (Figure 10-6). These usually are chronic infections and also have elevated globulin levels, hypoalbuminemia, inability to concentrate urine, and may have electrolyte abnormalities such as hypochloremia, hyponatremia, hypokalemia, and hypocalcemia. Therefore cattle with bilateral pyelonephritis and azotemia have a guarded prognosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree