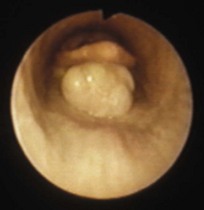

Chapter 1 1.1 Normal upper alimentary tract function: deglutition 1.2 Diagnostic approach to cases of dysphagia 1.3 Aetiology of dysphagia: oral phase abnormalities 1.4 Aetiology of dysphagia: pharyngeal phase abnormalities Pharyngeal compression: strangles abscessation Pharyngeal cysts, palatal cysts Epiglottal lesions, including sub-epiglottic cysts 1.5 Aetiology of dysphagia: oesophageal phase abnormalities 1.6 Oral trauma, mandibular fractures etc. 1.8 Anatomy of the oral cavity 1.9 Abnormalities of wear – abrasion and attrition 1.12 Endodontic disease including dental abscessation 1.13 Tumours of the upper alimentary tract 1.14 Diagnostic approach to dental disorders Clinical signs of dental disease Other ancillary diagnostic techniques Indications for dental extraction Options for the extraction of incisors, canines and wolf teeth Deglutition is divided into three stages: 1. The oral phase – which includes the gathering of food, movements within the oral cavity, mastication and the formation of boluses of ingesta at the base of the tongue – is under voluntary control. 2. The presence of a bolus gathered at the tongue base triggers the sequence of reflexes, collectively known as swallowing, which propels the ingesta from the pharynx – the pharyngeal phase – into the oesophagus. The glosso-pharyngeal nerve (IX) and the pharyngeal branches of the vagus (X) innervate the pharynx and larynx, and their afferent and efferent pathways are co-ordinated in the swallowing centre in the brainstem. 3. Waves of peristalsis convey the ingesta along the oesophagus to the stomach – the oesophageal phase of deglutition. The molar and premolar teeth are responsible for the mechanical crushing of the fibrous diet. The tip of the tongue assists in prehension and moves the ingesta between the cheek teeth. The glossal musculature receives its motor supply via the hypoglossal nerve (XII). The horse has an intra-narial larynx at all times other than during the momentary disengagement for deglutition. (See 5.18 and 5.21.) The signs of dysphagia include: Nasal reflux of ingesta points to an abnormality of the pharyngeal or oesophageal phase of deglutition (Figure 1.1). Thoracic auscultation should check for signs of inhalation pneumonia. Endoscopy per nasum is necessary to confirm whether pharyngeal paralysis is present (Figure 1.2). The usual findings consist of: • a mixture of saliva and ingesta on the walls of the nasopharynx. • persistent dorsal displacement of the palatal arch. • poor constrictor activity during deglutition. • failure of dilation of one or both ATD ostia during swallowing. Where functional pharyngeal paralysis is diagnosed, many horses are afflicted with pharyngeal hemiplegia, i.e. the pharyngeal neuropathy is unilateral, for example in cases of guttural pouch mycosis (see ‘Aetiopathogenesis’ in 5.6). True pharyngeal paralysis may be seen in cases of botulism. Conchal necrosis may accompany prolonged dental suppuration and may be seen on endoscopy of the nasal chambers (see ‘Conchal necrosis and metaplasia’ in 5.16). Provided that an endoscope with a diameter of 8.0 mm or less is available, the diagnosis of a palatal defect by inspection of the floor of the nasopharynx per nasum presents no difficulties, even in quite young foals (Figure 1.3). • epiglottal entrapment, with or without a sub-epiglottic cyst (see 5.22 and 5.23). • iatrogenic palatal defects after ‘over-enthusiastic’ staphylectomy. • fourth branchial arch defects (4-BAD syndrome) (see 5.25). • evidence of sub-epiglottic foreign bodies, usually in the form of unilateral oedema in the region of the ary-epiglottic folds. • intra-palatal cysts (see ‘Palatal defects’ in 5.28). • iatrogenic hyper-abduction of the arytenoid cartilage from prosthetic laryngoplasty or other evidence that ‘tie-back’ surgery has triggered dysphagia. • arytenoid chondropathy (see 5.24). • pharyngeal neoplasia (see Pharyngeal and laryngeal neoplasia in 5.28). • pharyngeal distortion by external compressive lesions such as neoplasia or abscesses. Facial paralysis inhibits the ability of a horse to prehend and retain ingesta in the oral cavity (see Chapter 11). Ankylosis of the joint between the stylo-hyoid and petrous temporal bones is often a feature of temporo-hyoid osteoarthritis (THO) in horses and may limit a horse’s ability to move the tongue (see ‘Temporohyoid osteoarthropathy, THO’ in 5.2) Simple midline linear defects of the soft palate are the most common cause of the nasal reflux of milk by foals in early life (Figure 1.3). Rarely, the midline cleft extends rostrally into the hard palate. Excessive palatal resection (staphylectomy) (see 5.21) in the treatment of dorsal displacement of the soft palate (DDSP) is irreparable. Inadvertent splits in the palate have been reported after the relief of epiglottal entrapment by section with a hooked bistoury passed per nasum in the standing horse (see 5.22). The presence of extra-mural soft-tissue swellings adjacent to the pharynx may cause dysphagia because of external compression of the pharynx and also, in the case of an abscess because of the pain associated with the movement of food boluses past the lesions (see Chapter 19). The increased mass of the epiglottis arising in entrapment by the glosso-epiglottal mucosa (see 5.22) or by a sub-epiglottic cyst (Figure 1.4) (see 5.23) causes dysphagia because of space-occupation and a restriction of the freedom for epiglottal retroversion. Secondary persistent dorsal displacement of the palatal arch may occur. Persistent DDSP is an indication for oral endoscopy and lateral radiography possibly using contrast medium. Both conditions are amenable to successful excisional surgery. Compromised glottic protection leading to the aspiration of ingesta into the lower airways may arise spontaneously in cases of arytenoid chondropathy, or through iatrogenic causes such as complications of prosthetic laryngoplasty or partial arytenoidectomy (see 5.20). The precise cause of post-laryngoplasty dysphagia is not known, but over-abduction of the arytenoid cartilage, the physical presence of the implants themselves and nerve injuries are amongst the suggestions which have been proposed. Removal of the prosthesis is often, but not always, effective in control of the dysphagia, but, of course, the respiratory obstruction for which the surgery was originally performed can be expected to return as the arytenoid cartilage reverts to its collapsed state. Approximately two thoroughbreds per thousand born are afflicted with defects of the structures which derive from the fourth branchial arch, specifically the wings of the thyroid cartilage, the crico-thyroid articulation, the crico-thyroideus muscle and the crico- and thyro-pharyngeus muscles (see 5.25). The fourth branchial arch defect (4-BAD) syndrome may arise unilaterally or bilaterally, and any or all of the structures may show partial or complete aplasia. When the 4-BAD syndrome includes aplasia or hypoplasia of the crico- and thyro-pharyngeal muscles the proximal oesophageal sphincter remains permanently open. Horses afflicted with 4-BAD usually present with abnormal respiratory noises at exercise, and it is most unusual for them to show dysphagia unless they are badly afflicted or there is another concurrent defect. Horses with 4-BAD may show bizarre eructation-like noises at rest and may be confused with wind-suckers. Obstruction of the oesophagus is discussed in greater detail at the end of this chapter (see 1.7). Impaction of dry fibrous material to occlude the lumen of the oesophagus, typically in the cervical segment, is the commonest cause of acute dysphagia in the horse. Older horses seem to be more susceptible but this may relate to the diets offered to horses which are not being fed for competitive exercise. In contrast, foals which are beginning to take herbage occasionally plug the oesophagus with a bolus of dry grass.

Upper alimentary system

1.1 Normal upper alimentary tract function: deglutition

Oral, pharyngeal and oesophageal phases of deglutition

Mastication

Lingual function

Elevation of palate

1.2 Diagnostic approach to cases of dysphagia

Physical examination, external and oral inspection

Endoscopy per nasum

1.3 Aetiology of dysphagia: oral phase abnormalities

Temporo-mandibular joint and hyoid disorders

Congenital and acquired palatal defects

1.4 Aetiology of dysphagia: pharyngeal phase abnormalities

Pharyngeal compression: strangles abscessation

Epiglottal lesions, including sub-epiglottic cysts

Laryngeal abnormalities

Fourth branchial arch defects (4-BAD)

1.5 Aetiology of dysphagia: oesophageal phase abnormalities

Oesophageal obstruction (‘choke’)

Veterian Key

Fastest Veterinary Medicine Insight Engine