Chapter 12 Unexplained Lameness

Lameness diagnosis is a never-ending challenge, even for an experienced clinician, because despite a logical and thorough investigation it still may prove difficult to reach a satisfactory conclusion. This chapter discusses some of the reasons why a definitive diagnosis may remain elusive. In some horses it may be possible to isolate the source of pain reasonably accurately, but it may not be possible to determine the cause of pain. In other horses the source of pain cannot be determined (see Chapter 97).

False-Negative Responses to Diagnostic Analgesia

The following are common case examples:

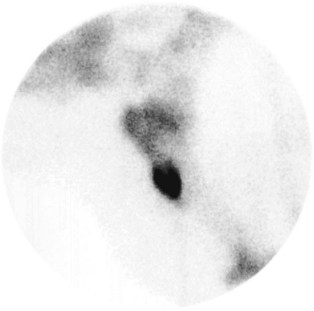

The horse in Figure 12-1 was admitted with suspected back pain but showed obvious bilateral forelimb lameness, with right forelimb lameness predominating. Digital pulse amplitudes were increased in the right forelimb, but there was no response to hoof testers. Nonetheless, the horse appeared clinically to have foot pain typical of laminitis. Apparent desensitization of the foot, performed to convince the owner that the horse had foot pain, produced absolutely no change in the lameness. The horse responded rapidly to treatment for laminitis.

Sources of Pain That Cannot Be Desensitized by Nerve Blocks

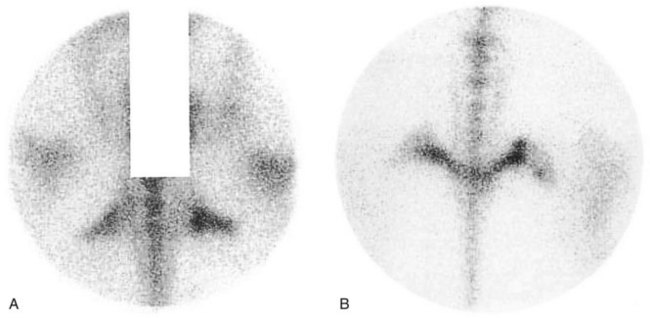

Many regions of the limbs proximal to the carpus and tarsus cannot be satisfactorily desensitized. In young horses, stress fractures are now well-recognized causes of lameness that pain from which in many circumstances cannot be blocked out. In young or older horses, fractures of the deltoid tuberosity of the humerus (Figure 12-2), the proximal aspect of the fibula (Figure 12-3), the third trochanter of the femur, and the tuber ischium (Figure 12-4) are all causes of lameness that are unaffected by nerve blocks.

Muscle injuries, such as tearing or fibrosis of brachiocephalicus or the pectoral muscles, may have no localizing signs (see page 152). Associated lameness cannot be influenced by nerve blocks. Atypical equine rhabdomyolysis can cause hindlimb lameness without any other clinical signs typical of tying up.

Periarticular lesions of the otifle such as collateral ligament injury are usually associated with detectable soft tissue swelling, but injuries of the patellar ligaments can occur with no localizing clinical signs, and associated pain is often unresponsive to intraarticular analgesia (see Chapter 46). I have also examined five horses with acute onset of severe lameness and mild swelling on the craniomedial aspect of the femoropatellar joint resulting in loss of palpable definition of the patellar ligaments. Lameness was characterized by a markedly shortened cranial phase of the stride at the walk, but less severe lameness at the trot. Ultrasonographic examination revealed the presence of a periarticular hematoma surrounding the patellar ligaments, which themselves were structurally normal.