CHAPTER 13 Unconventional Diets

A recent article published in the trade publication Petfood Industry reported a survey showing that 8 to 27 per cent of pet owners are considering a switch to a different brand of pet food.1 Many of these pet owners are making the switch to alternative pet foods labeled as “natural, organic, raw/frozen, refrigerated, homemade, 100 per cent U.S. sourced, locally grown,” as well as to other small-batch pet foods. Another survey conducted in May 2007 reported that 69 per cent of pet specialty retailers had seen increased sales of natural and organic pet food, while 21 per cent of pet-specialty retailers had seen a decline in sales of traditional pet food.1 This same survey also reported that sales of fresh and/or raw pet foods had increased by more than one third. With this movement toward alternative diets, the challenge for veterinarians and pet owners is to interpret and understand the terms and claims used to describe these unconventional pet foods.

REGULATORY DEFINITIONS

There is frequent confusion regarding the marketing terms and the regulatory purview they may fall under. Terms used in product promotional materials or on labels, such as natural, organic, human grade, premium, gourmet, and holistic often do not have officially recognized definitions (Box 13-1). Consumers (and veterinarians) often are left with the impression that any such language is standardized or regulated in some way, but that is not always the case.

Box 13-1 Descriptive Terms Used Commonly to Describe Commercial Pet Foods

derived solely from plant, animal or mined sources, either in its unprocessed state or having been subject to physical processing, heat processing, rendering, purification, extraction, hydrolysis, enzymolysis or fermentation, but not having been produced by or subject to a chemically synthetic process and not containing any additives or processing aids that are chemically synthetic except in amounts as might occur unavoidably in good manufacturing practices.2

The term organic refers to the conditions under which the ingredients used in products, and the product itself, were produced, and must be consistent with regulations developed by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Current regulations covering organic products do not apply to pet foods; however, the USDA is developing regulations for organic labeling of pet foods. The USDA Organic Pet Food Task Force issued a report in 2006 outlining some of their proposed regulatory changes.3 The Task Force recommended that product composition requirements for organic pet food be similar to those for livestock, but that labeling categories be the same as for processed human food. These require a minimum of 70 per cent organic ingredients for the use of the claim “made with organic,” and at least 95 per cent organic content for the use of the claim “organic.” All products labeled as “made with organic ingredients” or “organic” must exclude ingredients that are genetically engineered, are produced using sludge or irradiation, or contain synthetic substances not on the National List of Allowed and Prohibited Substances as defined by the National Organic Standards Board (advisory to the federal Secretary of Agriculture). They also can not contain sulfites, nitrates or nitrites, or organic and nonorganic forms of the same ingredients. In addition, products labeled “organic” can not contain nonorganic ingredients when organic sources are available.

Another term that is gaining use is human grade. Currently, there is no official definition or regulation regarding the use of this term. According to AAFCO, this means that the term is not allowed.4 However, there is no legal prohibition, and the term continues to be applied widely to a variety of pet foods. In 2007, one pet food company was denied the right to sell their product in the state of Ohio due to the use of the term human food grade.5 The Ohio State Department of Agriculture argued that the term was misleading and refused to grant a license to the company. The company followed with a lawsuit, which eventually sided in their favor due to the argument that the company had the constitutional right to make truthful statements about the quality of its pet food product on the label. So, despite the unclear and likely variable and inconsistent interpretation of the term, its use is gaining popularity as more pet owners are selecting foods with improved safety and quality, whether these qualities are true or perceived.

HOME-PREPARED DIETS

Although many recipes for home-prepared cat foods are available on the Internet and in books, the majority of these diets are inadequate when compared to updated recommendations for nutrient intakes using modern ingredient databases and formulation methods. The recipes also tend to have vague instructions, contain errors or omissions in formulation, incorporate potentially problematic ingredients, or feature outdated or otherwise inappropriate strategies for addressing specific disease conditions. One study evaluated recipes available in popular books and compared the analyses to nutrient-intake recommendations established by AAFCO and the National Research Council. Many of these widely available recipes were found to provide less-than-recommended amounts of multiple essential nutrients, including taurine, minerals, and vitamins.6 Another issue is that some owners do not follow any particular recipe, do not provide nutritional supplements, or feed their cats solely items that are palatable or convenient. Also, because certain feeding styles have become popular (such as raw diets), additional concerns must be addressed.

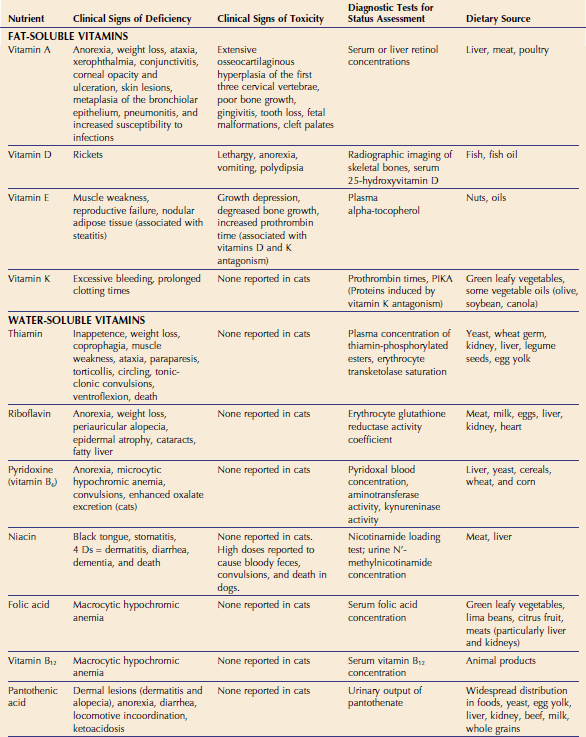

Nutritional adequacy is a major concern in regard to home-prepared diets. Providing appropriate levels of essential nutrients is crucial to optimize health and longevity, the foremost goals of individualized nutritional management (Table 13-1). Formulations are inherently imperfect at providing accurate levels of essential nutrients to the individual animal due to limitations in nutrient database information, variation in the nutritional profiles and preparation of the ingredients, limitations of the formulation methodology and/or software, limitations of the current understanding of the nutrient requirements of individual animals, and the inability to assess customized diets for appropriate digestibility and bioavailability of the nutrients. One study that evaluated the nutritional adequacy of home-prepared dog foods by laboratory analysis demonstrated that 35 different diets were below AAFCO recommendations for calcium, vitamins A and E, zinc, copper, and potassium.7 Another study utilized computer analysis to assess home-prepared diets that were recommended for the diagnosis and/or treatment of adverse reactions to foods in dogs and cats.8 Compared to nutrient intake recommendations at the time, most recipes that were recommended for long-term feeding of adult cats were too low in calcium, iron, taurine, and thiamin, and some also provided inadequate levels of potassium, phosphorus, and sodium. Owners should understand the limitations of any diet they choose to feed, and they should have the tools and guidance available to evaluate resources and recipes effectively, so that informed decisions can be made regarding an appropriate diet for individual animals. This is particularly important when feeding cats with one or more diseases amenable to nutritional management because disease progression or other changes in the clinical picture may warrant changes in the feeding plan.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree