Chapter 21. Tumors of the Thoracic Cavity

SECTION A Primary Respiratory Tumors

Leslie E. Fox and Kerry C. Rissetto

Incidence—Morbidity and Mortality

Primary lung tumors are uncommon in dogs and rare in cats but have been diagnosed more frequently in the past decade. 1 Although metastatic neoplasms are far more common than primary lung tumors, carcinomas/adenocarcinomas are the most common histology of tumors originating in the lungs of dogs and cats. 2 They are almost always malignant. Dogs and cats are typically older (average, 9–12 years), but these tumors may occur in young animals. 2

Often dogs have no clinical signs suggesting the presence of a primary lung tumor. 1,2 If dogs are presented for signs referable to the respiratory tract, the most frequent abnormality, seen in 52% to 58% of primary lung tumor patients, is a chronic, nonproductive cough that fails to respond to antimicrobial and symptomatic therapies. 3-5 Other clinical findings may include dyspnea, tachypnea, hemoptysis, and cyanosis, often with inappetence and subsequent weight loss. The original reason for presentation may be less obvious, including lameness caused by hypertrophic osteopathy (HO) (the most common paraneoplastic syndrome), dysphagia, fever, cranial vena cava obstruction leading to head and neck edema, ascites, pleural effusion, spontaneous pneumothorax, and diarrhea. 5 Cats are often symptomatic with dyspnea and/or tachypnea and coughing with or without lethargy, anorexia, and weight loss, but may be presented for only nonrespiratory signs like fever and decreased appetite. 2,6,7 Lameness in cats may be the only presenting clinical sign and is most likely due to lung-digit syndrome, in which metastasis from the primary lung tumor to one or more digits causes pain, swelling, paronychia, and pododermatitis unresponsive to antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory therapies. 8,9 In addition, cats often have serious concurrent illness, but usually do not have feline leukemia or feline immunodeficiency virus infections. 6

Etiology and Risk Factors

Airborne carcinogens probably contribute to the development of lung cancer in cats and dogs, just as they do in people. An association between second-hand smoke and lung cancer has been made for both mesocephalic and brachycephalic breeds, with the hypothesis that a longer nose may confer a protective effect via additional turbinate filtration. 10 There may also be an association between urban environments and the development of these tumors. 3

Diagnosis and Staging

Radiographic evidence of a solitary, well-circumscribed lung parenchymal mass in a middle-aged to older dog or cat raises the suspicion for primary or secondary neoplasms; however, lung tumors can present with almost any radiographic pattern in any age animal. 11,12 Because vascular, lymphatic, and alveolar tumor spread may be simultaneous, primary lung cancer is often observed radiographically as a solitary mass, but also as disseminated multifocal or diffuse parenchymal or interstitial patterns sometimes with lobar consolidation and/or pleural effusion. Abscesses, pneumonia, fungal granulomas, lymphomatoid or eosinophilic pulmonary granulomatosis, hematomas, pulmonary thromboembolism, cysts, bullae, and metastatic lung tumors are differential diagnoses for solitary or multifocal lung masses. Pneumonia, primary and metastatic lung neoplasms, granulomatous diseases and hemorrhage, edema, and fibrosis are differentials for disseminated pulmonary patterns. Multicentric neoplasms that may affect the lung parenchyma simultaneously with systemic abnormalities include lymphoma, malignant histiocytosis, metastatic histiocytic sarcoma (in dogs), and rarely, mast cell tumor (also in dogs).

Presurgical diagnosis of primary lung tumors involves ruling out non-neoplastic and metastatic cancer as causes for the observed radiographic findings with fine needle aspiration and cytology or histopathological examination of a biopsy specimen. A complete blood count including platelet count, serum biochemical panel, urinalysis, and coagulation panel or activating clotting time can be used to assess potential risks of hemorrhage and anesthetic complications and to assess for concurrent illness. Feline leukemia virus antigen, feline immunodeficiency virus antibody, and serum l -thyroxine assays are recommended for cats. Transthoracic fine-needle aspiration (25- or 27-gauge, 1.5-inch needle on a 6-ml syringe) or core biopsy (20-gauge Wescott needle) of peripherally located discrete nodules and tracheobronchial lymph nodes (TBLNs) can be effectively guided using ultrasound, fluoroscopy, or CT. 13,14 In fact, a recent study showed cytologic agreement with histopathology in an impressive 82% of cases. 14 Serious complications are infrequent and mainly include pneumothorax or hemothorax. A repeat thoracic radiograph taken 4 to 8 hours after the procedure or observation overnight is recommended after transthoracic aspiration/needle biopsy.

If a preliminary diagnosis cannot be determined from a cytologic or needle tissue biopsy sample and moderately invasive technique is desired, additional tissue obtained via thoracoscopy or limited thoracotomy will usually help distinguish neoplastic disease from non-neoplastic causes of parenchymal masses. Since surgical excision is the treatment of choice for resectable masses, confirmatory histologic specimens of suspected neoplasms are easily obtained during therapeutic thoracotomy via an intercostal or median sternotomy approach.

Clinical staging of primary lung tumors consists of thoracic radiographs or advanced imaging for tumor lung lobe localization and evidence of regional intrathoracic spread, as well as histopathological evaluation of TBLNs. Even normal-sized lymph nodes should be examined histologically. In one study, CT evaluation of TBLN status agreed with histopathology in 93% of cases, versus only 57% for thoracic radiographs. Therefore, dogs without radiographic evidence of tracheobronchial lymphadenomegaly benefit from preoperative thoracic CT for a more complete assessment of regional metastasis, as well as a better indicator of prognosis. 15 If the preliminary cytologic examination suggests that the pulmonary disease is likely metastatic, a careful search of the abdomen with plain radiography and an ultrasonogram will complement a complete physical examination in identifying a tumor elsewhere in the body. The prostate, urinary bladder, and mammary glands are common extrathoracic sites.

Metastasis

Since the majority of primary lung tumors are carcinomas, there is reason to assume that most metastasis occurs through the lymphatics. However, metastasis can also be vascular, alveolar (by local cell migration in the airways), or through the pleura. Local metastasis to structures in the thorax is more common than systemic spread to bones and intra-abdominal organs. In greater than one third of all cases, multiple lobes are affected, and this will dramatically change surgical treatment options. 3 Regional lymph nodes (tracheobronchial and mediastinal) are the most common sites of intra-thoracic spread. The pattern of metastasis in cats is similar, but the metastatic rate is higher (>75%) at the time of diagnosis, likely due to a greater incidence of poorly differentiated carcinomas as well as the stoic nature of the feline patients, delaying outward clinical signs. 6,16 P2 and P3 are common sites of metastasis (i.e., lung-digit syndrome) for cats with primary pulmonary carcinomas and may be present in multiple toes and feet simultaneously. In fact, in a study examining cats with digital carcinomas, 87.5% were actually metastases from a primary lung carcinoma, with only 12.5% being primary digital tumors. 9 Thus, thoracic radiographs are always warranted prior to amputation for neoplastic digital lesions in feline patients.

Treatment

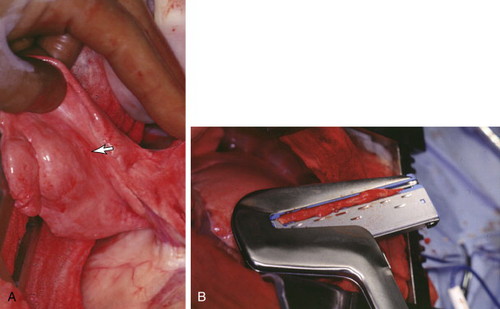

Whenever possible, lobectomy or partial lobectomy offers the best chance for the longest disease-free interval and survival ( Figure 21-1 ). When treating canine patients, in which over half of all lung cancers affect only one lobe, immediate surgical excision is advised since small tumor size (<5 cm diameter) and completeness of tumor excision are associated with better outcomes. 2,4 Radiation and chemotherapies are largely untried. Inhalation chemotherapy has provided measurable responses in approximately 25% of treated dogs. 17 Improved targeting and safer methods of inhalant drug delivery are currently under investigation. Systemic chemotherapy is indicated for dogs and cats with pulmonary lymphoma, lymphomatoid granulomatosis, malignant histiocytic diseases, and mast cell neoplasms. Additional information regarding diagnostics, clinical staging, and multi-drug protocols for these diseases are found in the corresponding chapters. Systemic chemotherapy may also be warranted as adjuvant treatment for patients after surgical removal of the primary lung tumor. A partial response was observed in two dogs with gross evidence of bronchoalveolar carcinoma using vinorelbine, a mitotic inhibitor (given at 15 mg/m 2 , IV infusion over 5 minutes, every 7 days), and may be helpful for dogs with residual microscopic disease. 18 The benefit of vinorelbine is its ability to achieve 13.8 times greater concentrations in lung tissue than other vinca alkaloids. 1,19 The dose-limiting toxicity is typically neutropenia. Piroxicam is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug that indirectly decreases tumor proliferation, angiogenesis, and resistance to apoptosis and may be useful in the treatment of either primary or secondary lung carcinomas (0.3 mg/kg PO, once a day). 20 Intracavitary chemotherapy (carboplatin or mitoxantrone) has also shown some success in treating dogs with thoracic or abdominal carcinomatosis, sarcomatosis, or mesothelioma, with one study achieving a median survival time of 332 days in treated patients versus 25 days in the control group. 21

|

| FIGURE 21-1 A, Intraoperative appearance of a primary pulmonary adenocarcinoma in a 12-year-old dog. B, The mass was completely excised via partial lobectomy. |

Although radiation therapy might improve control of incompletely resected tumors, radiation damage to intrathoracic structures with conventional radiation therapy is frequent and problematic. 22 However, newer methods for more precise delivery of local therapy can minimize normal tissue cell kill. One such treatment modality is intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), which uses multiple collimator beams to three-dimensionally conform to the tumor and minimize radiation doses to normal tissue surrounding it. 23 Another potential method of local treatment is called radiofrequency ablation (RFA) in which an electrode is percutaneously placed in the tumor and uses electrical currents to induce tumor cell necrosis. 24 Treatment of paraneoplastic HO, a periosteal proliferation of long bones, includes complete excision of the lung tumor that provides pain relief within 3 to 6 weeks and resolution of bone lesions only months later. Pain management with NSAIDs or corticosteroids is also helpful. 25

Prognosis and Survival

The overall post-surgical median survival times for dogs is more favorable than for cats (11 months vs. 4 months, respectively) possibly because in cats, lung tumors are less well differentiated than in their canine counterparts, and the disease is usually more advanced at the time of detection. 3-7,26 However, the survival times for both species are longer when favorable prognostic factors are present (up to 26 months for dogs and 22 months for cats). Prognostic factors associated with longer survival times for dogs are reported as lack of clinical signs referable to their tumor (i.e., no coughing), normal-sized TBLN assessed intra-operatively and/or radiographically, histologic absence of tumor cells in the TBLN, lower histologic grade tumor, well-differentiated adenocarcinomas, low-grade papillary carcinoma, peripherally located tumors amenable to complete surgical excision, small tumors (<5 cm diameter), solitary tumors without metastatic disease, lack of pleural effusion, and complete surgical resection of the primary disease. 1-5,26 Post-surgical survival for cats is longer when pleural effusion, lymphatic or vascular invasion, and embolic, intrapulmonary, or TBLN metastasis are absent. A greater prognosis is also afforded to patients with moderately to well-differentiated tumors that are completely resected without evidence of metastasis. 6,7

Selected References ∗

J.D. DeBerry, C.R. Norris, V.F. Samii, et al. , Correlation between fine-needle aspiration cytopathology and histopathology of the lung in dogs and cats , J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 38 ( 2002 ) 327 ;

A retrospective study of patients with spontaneous pulmonary disease found fine-needle aspiration cytology to accurately reflect histopathology in >82% of cases .

K.A. Hahn, M.F. McEntee, M.M. Paterson, et al. , Prognosis factors for survival in cats after removal of a primary lung tumor: 21 cases (1979-1994) , Vet Surg 27 ( 1998 ) 307 ;

A retrospective study demonstrating prognostic factors for survival after attempted complete excision .

T.M. Jacobs, M.J. Tomlinson, The lung-digit syndrome in a cat , Feline Pract 25 ( 1997 ) 31 ;

Veterinary and human literature is reviewed in light of the case presentation, which demonstrates typical features of lung-digit syndrome resulting from a pulmonary carcinoma .

E.A. McNeil, G.K. Ogilvie, B.E. Powers, et al. , Evaluation of prognostic factors for dogs with primary lung tumors: 67 cases (1985-1992) , J Am Vet Med Assoc 211 ( 1997 ) 1422 ;

Associations between clinical and histologic factors and outcome for dogs with primary lung tumors are made and a histologic grading system is suggested in this retrospective study .

V.J. Poirier, K.E. Burgess, W.M. Adams, et al. , Toxicity, dosage, and efficacy of vinorelbine (Navelbine) in dogs with spontaneous neoplasia , J Vet Intern Med 18 ( 2004 ) 536 ;

The first evaluation of vinorelbine (a mitotic inhibitor) for use in dogs with cancer .

K.C. Rissetto, P. Lucas, T.M. Fan, An update on diagnosing and treating primary lung tumors , Vet Med 103 ( 3 ) ( 2008 ) 154 ;

A review article summarizing diagnostic and treatment options for small animal patients with lung cancer .

SECTION B Mediastinal Tumors

Annette N. Smith

KEY POINTS

• Thymoma and lymphoma are the most common tumors of the cranial mediastinum.

• Cytology may aid in differentiation of lymphoma from thymoma if lymphoblasts are present on review of a mediastinal mass aspirate.

• Surgery is the treatment of choice for non-invasive thymomas.

• Radiation is useful in the palliation of non-resectable thymomas and mediastinal lymphoma.

Incidence—Morbidity and Mortality

Lymphoma and thymoma are the most common cranial mediastinal masses diagnosed in companion animals. 1 Lymphoma is the most frequently diagnosed mediastinal malignancy in both the dog and cat, whereas thymomas are uncommon in the dog and rare in the cat. 2 The cranial mediastinum is the primary site of lymphoma in approximately 5% of canine lymphoma patients 3 and a common site of disease for feline leukemia positive (FeLV+) cats. A list of differential diagnoses for mediastinal masses 1-5 can be found in Box 21-1 .

BOX 21-1

LIST OF DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES FOR MEDIASTINAL MASSES 1,2,4,5

Lymphoma

Thymoma

Ectopic thyroid tissue

Ectopic thyroid carcinoma (follicular or medullary)

Branchial cyst

Chemodectoma

Neuroendocrine carcinoma

Expansile chest wall mass

Lymphangiosarcoma

Osteosarcoma

Liposarcoma

Soft tissue sarcoma

Fibroma

Undifferentiated sarcoma

Tracheal or esophageal tumor

Metastatic tumor

Lymphadenopathy (infectious or inflammatory)

Bacterial granulomas

Fluid (transudate, exudate, or hemorrhage)

Fat

Etiology and Risk Factors

Lymphoma is typically a disease of middle-aged to older animals with the exception of the FeLV-associated form, which primarily occurs in young cats. 1,6-10 Siamese and Oriental breeds are over-represented in some reports. 1,6,7,9,11 Thymomas are most common in older animals, and medium- to large-breed dogs may be over-represented. 12-14 The median age reported for nine dogs with mediastinal carcinoma was 10 years, with no breed or gender predisposition noted. 5

Clinical Features

Dyspnea, coughing, and exercise intolerance can all be associated with a space-occupying mediastinal mass. On physical examination, lung sounds are often muffled, heart sounds are muffled or displaced, and, in cats or small dogs, chest compliance may be decreased. Regurgitation/vomiting or gagging can occur as a result of esophageal compression or megaesophagus associated with thymoma-associated paraneoplastic myasthenia gravis. Aspiration pneumonia and recurrent weakness or collapse can be associated with generalized myasthenia gravis. Invasion or compression of the cranial vena cava by the mediastinal mass can result in swelling of the head, neck, and/or thoracic limbs, known as precaval syndrome. 15-19

The most common paraneoplastic syndrome associated with mediastinal masses is hypercalcemia. Up to 50% of canine patients with hypercalcemia have cranial mediastinal lymphoma. 20,21 The hypercalcemia may cause clinical signs, such as polyuria/polydipsia, that would prompt a client to seek veterinary care. Hypercalcemia is not only related to lymphoma, but has also been reported with other mediastinal masses including thymoma. 13,22 See Box 21-2 for reported paraneoplastic syndromes associated with thymoma. 12-14,22-31 Paraneoplastic myasthenia gravis occurs sporadically in cats and in up to 40% of canine patients with thymoma. 12-14,23-28

BOX 21-2

LIST OF REPORTED PARANEOPLASTIC SYNDROMES ASSOCIATED WITH THYMOMA

Myasthenia gravis 12-14,23-28

Hypercalcemia 13,22

Polymyositis 23,29

Skin disease 29-31

Hypogammaglobulinemia 29

Non-thymic tumors 12

Arrhythmias 13,25

Diagnosis and Staging

Establishing the definitive diagnosis for a mediastinal mass is imperative for appropriate treatment recommendations to be made. Cytologic or histologic samples are necessary to establish a diagnosis.

Blood Work

Although rarely diagnostic, neoplastic lymphocytes may be present in the circulation, supporting a diagnosis of lymphoma. Paraneoplastic hypercalcemia may be noted and supports a diagnosis of lymphoma or thymoma in pets with known mediastinal masses. Acetylcholine receptor antibody testing should be considered in all cats with thymoma, since they may be asymptomatic for myasthenia gravis. Dogs presenting with clinical signs such as megaesophagus, aspiration pneumonia, or generalized weakness should also be tested.

Imaging Studies

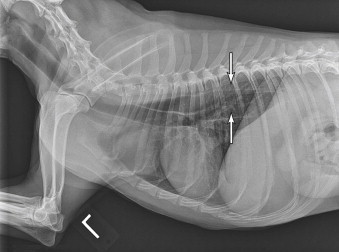

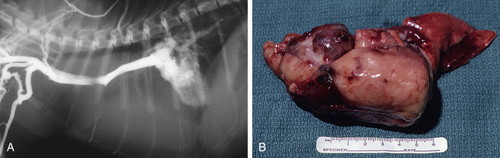

Tracheal elevation on the lateral radiographic images is a consistent sign of a mediastinal mass ( Figure 21-2 ). Positioning can also cause tracheal deviation; a mass that deviates the trachea should be obvious. Differentiating a pulmonary or chest wall mass from a mediastinal mass is best done with the V-D image. The normal mediastinum should be twice the width of the spine in the dog, and the width of the sternum in the cat. A widened mediastinum suggests the presence of a mass ( Figure 21-3 ); however, fat can widen the mediastinum in the absence of a true mass. Pulmonary masses are usually lateral to the mediastinum, and chest wall masses tend to be peripheral, causing rib lysis or spreading. Malignant or chylous pleural effusion resulting from obstruction or invasion of the thoracic duct and other lymphatics may be present. 32,33 Esophagrams and angiograms ( Figure 21-4 ) may be useful in determining invasiveness, and thus resectability of mediastinal masses. 16 An esophagram can also be used to confirm megaesophagus if not apparent on plain films. Ultrasound of the cranial mediastinum can be useful in differentiating a cranial mediastinal mass from pleural fluid and may be helpful in determining the best aspiration or biopsy site. 34 Lymphoma is generally homogenous in echotexture, whereas thymomas and other masses are more frequently mixed with areas of cavitation. 35 CT scan or MRI is useful for determining invasiveness of thymomas or other masses in order to plan surgical resection or radiation treatment of the tumor. 36

|

| FIGURE 21-2 Lateral radiograph of a dog with a cranial mediastinal mass as evidenced by tracheal elevation. Note the presence of megaesophagus (arrows). (Courtesy Dr. Greg Almond, Auburn University.) |

|

| FIGURE 21-3 A widened cranial mediastinum suggests the presence of a mediastinal mass. In this case, the diagnosis was thymoma. (Courtesy Dr. Greg Almond, Auburn University.) |

|

| FIGURE 21-4 A , Contrast radiographs (angiogram) showing displacement of the heart by a large mediastinal mass in a cat. B , Gross appearance of the mass noted radiographically in A . The diagnosis in this case was thymic lymphoma. (Courtesy of the University of Missouri Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital Oncology Service.) |

Fine-Needle Aspiration and Cytology

Aspiration cytology may be helpful in determining the diagnosis for a mediastinal mass and can differentiate thymoma from lymphoma in many instances. Thymomas should contain three cell types: mature lymphocytes, neoplastic epithelial cells, and mast cells. Cytologic diagnosis is difficult when all three components are not present in the aspiration sample. Lymphomas are usually lymphoblastic, with large, immature lymphocytes. Flow cytometry of the mass aspirate to determine a clonal neoplastic population may be useful to confirm a diagnosis of lymphoma. 37 Cytology of pleural effusion can also be diagnostic for lymphoma if exfoliated lymphoblasts are present. 32,33

Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry

Histopathology is the definitive diagnostic test for mediastinal masses. Thymomas can be cystic, so a blind biopsy may give non-diagnostic results. Open surgical biopsy, ultrasound, or CT guidance will often provide the best sample. Multiple samples should be obtained since cystic areas may be filled with hemorrhage and necrotic debris. In addition, the morphology of the samples may be highly variable depending on the area biopsied. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) may facilitate diagnosis. A variety of IHC markers including CD3 (T-cell lymphoma), CD79 (B-cell lymphoma), cytokeratin (thymoma), synaptophysin and chromogranin (neuroendocrine tumors) and TTF-1 (thyroid tumor), thyroglobulin (thyroid follicular cell), and calcitonin (thyroid medullary cell) are available to help differentiate among the most likely diagnoses. 5

Metastasis

Thymomas are generally classified as invasive or non-invasive , 2,38,39 rather than malignant or benign unless a rare diagnosis of thymic carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma 1,40,41 is made. Thymomas rarely metastasize, although spread beyond local invasion has been reported. 42-44 Thymic carcinomas can be metastatic to distant sites, including lymph nodes, other mediastinal sites, pleura, and lungs. 1 Cranial mediastinal carcinomas have also been reported to metastasize, namely to the lungs and mediastinal lymph nodes. 5

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree