Chapter 70 Treatment of Elephant Endotheliotropic Herpesvirus

Although the number of elephant endotheliotropic herpesvirus (EEHV) cases continues to increase, the survivor list has remained disappointingly small. This has confounded the identification of worthwhile treatment modalities. In addition, outcome is also likely affected by variables unrelated to treatment, such as viral load, strain virulence, and immune status. Nevertheless, growing evidence from antemortem blood work, case reports, and necropsies has suggested that shock and hypotension, along with possible disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), develop as EEHV progresses. In this way, EEHV infection, a peracute to acute hemorrhagic disease, clinically resembles some human hemorrhagic diseases, such Dengue fever and Ebola,19 although the mechanisms underlying shock in elephants with EEHV are not known.

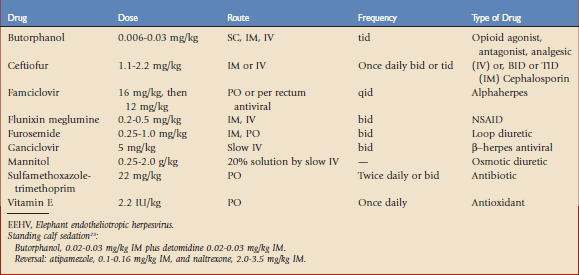

Many facilities now specifically train their juvenile elephants to accept various medical procedures to facilitate herd monitoring as well as crisis management. However, sedation is indicated for some animals, facilities, or procedures. A successful protocol that has been used in juvenile elephants is presented in Table 70-1. Risks of sedation may be decreased by having an accurate weight, choosing standing sedation over recumbent sedation, using reversible sedatives, having adequate padding to support the patient if recumbency occurs, and monitoring vital signs.

With the recent report of the death of an elephant caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and the growing suspicion that some EEHV patients have compromised immune systems, attention to hygiene and biosecurity is paramount.12 Frequent hand washing, removal of waste products from the environment, and excellent sanitization are strongly recommended. Additional equipment and supplies are described in the following sections.

Physical Examination and Monitoring

Many facilities routinely monitor a variety of parameters in their herds, including complete blood counts (CBCs) and serum blood chemistries, to identify changes that may foreshadow clinical disease. Some institutions also ship blood regularly to the National Elephant Herpes Laboratory in Washington DC for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of whole blood for EEHV. The recent finding that healthy elephants may shed virus in nasal secretions suggests that frequent trunk wash screening could be useful, although currently this is only available for research purposes.22 Useful physical and blood monitoring parameters in elephants are listed in Box 70-1.

BOX 70-1 Parameters to be Monitored in Elephant Endotheliotropic Herpesvirus Patients

Eating, drinking, and nursing behavior

Urinalysis with dipstick and refractometer

Presence or absence of edema (head, elsewhere)

Presence or absence of borborygmi

Feces: consistency and frequency

Ultrasound assessment of thorax, abdomen

Physical Findings

Mentation and behavior are subjective, and ideally should be observed by individuals familiar with the elephant. Some EEHV patients are described as lethargic or somnolent.7 Others refuse to lie down to sleep. Brain imaging techniques are not currently possible in elephants, but procedures that might distinguish between general malaise and elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) caused by vasculitis include an ophthalmic examination to look for papilledema and retinal hemorrhage, as well as cranial nerve evaluation. In animals suspected to have increased ICP, oxygen therapy and mannitol in conjunction with fluid therapy to correct hypovolemia and maintain blood pressure should be considered. Oxygen may be administered at 10 to 20 liters/min from a portable tank through tubing placed into the trunk if the animal permits it, or in a flow-by manner.9 Mannitol, an osmotic diuretic used to treat elevated ICP, has not been evaluated in elephants, but the equine dose might be an appropriate starting point.

Edema, especially of the head, neck, and tongue, may become severe enough to impede breathing, prevent swallowing, and cause skin fissures, although total protein and albumin levels may not immediately correlate with the severity of edema. Colloidal support, oxygen therapy, and diuretics may be helpful. Furosemide has been used in elephants at empirical doses extrapolated from equine data.21 It must be used with caution in shocky patients and in patients receiving nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

The soft and hard palates, tongue, and buccal surfaces of the mouth should be examined for oral ulcers or vesicles. Discomfort from such lesions, or from others located in the larynx or esophagus, may contribute to anorexia. The conjunctiva and genital mucosa, as well as the sclera, should be assessed for lesions, injected vessels, and color changes. Cyanosis is a significant finding that ideally should be correlated with a pulse oximetry reading or measurement of Pao2. Although pulse oximetry may be challenging in elephants, usable probe sites include the finger of the trunk, tongue, upper lip, pinna of the ear, and distal nasal septum. A caveat is that these devices are designed to read the oxygen saturation (Sao2) of human hemoglobin (Hb), which has a lower oxygen affinity than elephant Hb. Thus, a high Sao2 reading could, in fact, correlate with a lower Pao2.10 Supplemental oxygen should be provided to cyanotic patients and those with low Sao2 and Pao2.

Abdominal pain, another nonspecific sign, is commonly reported.7 Decreased borborygmi, inappetance, or scant manure may be caused by impaction from dehydration or viral damage to the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Diarrhea may also be caused by viral injury. However, because elephants are prone to a variety of nonviral causes of colic, even in a confirmed EEHV case, other diagnoses should be considered. Treatment of colic signs is symptomatic.

Decreased urine output and/or the presence of blood or protein in the urine may indicate renal compromise caused by inadequate circulation. Except for very young calves, elephants do not concentrate their urine very well, and specific gravity does not indicate hydration status.26 Standard signs of dehydration such as sunken eyes or decreased skin turgor are rarely observed in elephants. The patient’s water and milk consumption should be assessed to correlate input with output. Sick elephants should be weighed daily, if possible.

EEHV patients often present with low-grade fever. Normal fecal ball temperatures are 35° C to 37° C (96.8° F to 98.6° F).1 A subcutaneous microchip that measures body temperature has been developed for horses and is currently being tested in elephants. Fever does not necessarily require treatment, but is a useful monitoring tool.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree