Rebecca M. Gimenez

Trailer or Vehicle Accidents

Horses are transported more often than any other type of livestock, sometimes hundreds or even thousands of times in their working years. Drivers are frequently untrained, and trailers may be inadequately maintained or incorrectly hitched. An inappropriate towing vehicle or incorrect hitching may cause a sway that results in a jackknife incident. Best practices to prevent wrecks and horse injury are shown in Box 1-1.

Incidents with horse trailers occur during all phases of transport: loading, underway, and unloading, but the injuries most frequently attended to by veterinarians are those incurred when horses scramble, rear, or rush onto or off of the trailer. This chapter mostly addresses accidents during transportation; in many instances, these wrecks become unloading operations that must be upgraded to emergency extrication by professional responders. These situations involve far more than opening the gate of the trailer and leading the horse out. Every wreck is different, and there is no standard operating procedure that can be applied to every incident, but best practices in equine technical rescue do exist for handling these incidents.

Modern practitioners must be part of the local emergency response team using the Incident Command System (ICS; Box 1-2). By law, if an accident occurs on a roadway, a person must call 911 in the United States, 000 in Australia, or 999 in the United Kingdom. The veterinarian must communicate using the emergency response language of ICS to make the extrication of the horse as efficient and safe as possible. Medical stabilization often must be started before a horse’s extrication, because horses are physiologically fragile, and an injured horse may steadily be deteriorating inside the wreck. In many cases, hours to days after a seemingly successful rescue, horses can die unexpectedly as a result of stress, ischemia reperfusion syndrome, hypothermia, or complications of shock.

Always Involve Emergency Services

Veterinarians should involve 911 emergency services personnel from the beginning, whether the incident is a trailer overturn, a horse trapped over or under a chest bar, or a hoof caught in a divider, for example, because it speeds up overall efficiency of the response. The 911 services have evolved tactics, techniques, and procedures that yield superior results because they are constantly evolving but also are built on a foundation of past field experience. Responders must consider safety of both human responders and the animals; available human, equipment, mechanical, and logistical resources; the weather; medical issues such as the stability of the patient and arrival time of medical treatment; and any unusual situational concerns such as accessibility, stability of the wrecked vehicle or trailer, and structural integrity of involved fixtures. For example, is the overturned trailer still attached but yawing out over the side of a bridge? The 911 personnel attend to such situations daily; a veterinarian may attend such a wreck once in an entire career.

Role of the Practitioner

Accidents present many dangerous scenarios in which the veterinarian is not the authority with jurisdiction over the scene; usually it is the fire department or police officer first on site. The practitioner must fit into the ICS because the incident commander is ethically and legally responsible for the safety of all personnel and must evaluate the risk and benefit of strategies for horse extrication. Firefighters and police officers control traffic, extricate people, and assist with bystanders and frantic owners. Paramedics deal with human injuries, and the incident commander will consider assisting the animals when the scene is stable and safe. The veterinarian should then assess horse viability and consult with the horse owner to make timely decisions regarding treatment or euthanasia. From the perspective of the animal, the wreck is very different from that perceived by rescuers. Rubber mats, horse bodies, and divider gates have each reacted to impact based on gravity and momentum vectors. Recumbent animals entrapped in an overturned trailer are subject to abnormal orientation. Gravity acting on the horse’s weight, sometimes for several hours, can lead to muscle ischemia, with subsequent hyperemia and reperfusion injury developing after rescue. These factors as well as injuries to body systems must be taken into account to provide appropriate owner advice and timely treatment of the animal (see Chapters 3 to 11).

Head, neck, and lower limb injuries are the most frequently reported by practitioners after trailer wrecks. When the horse falls forward into the chest bar or bulkhead area at impact, the first area to absorb the blow is the face and neck, and then the lower limbs are injured as the animal scrambles to stand up. Horses are astonishingly capable of surviving even catastrophic trailer wrecks—as long as they remain inside the trailer. However, the mass of the horse creates sufficient momentum to propel the horse through bulkhead walls, doors, and windows. If the horse is ejected or the trailer disintegrates, death is instantaneous, or the prognosis for survival is poor.

Horses that appear to be lying calmly are actually extremely stressed; recumbent and trapped horses often lie quietly for a few minutes because of exhaustion, but their instinct is to rise to their feet, struggle, and run away. In the process, alpha horses may bite or kick horses with lower rank that are unable to escape. They do not reason that humans are there to assist. Horses can hear the voices, tools, vehicles, footsteps, and extrication equipment. Outside the trailer, they may be able to see shadows and reflections. Loud sounds such as those from sirens or cutting equipment must be limited until absolutely necessary, and once a tool is started, it should be kept running. Animals seem to accommodate to the sounds and vibration associated with such equipment if the tools are used efficiently. Remember that air chisels and reciprocating K-12 and chain saws are very loud, whereas others, like the hydraulic jaws of life, are silent but cut very jagged edges. Selection and use of cutting tools are the responsibility and expertise of the fire department; trailer construction materials run the gamut from wood to steel and fiberglass, and all require different strategies for extrication.

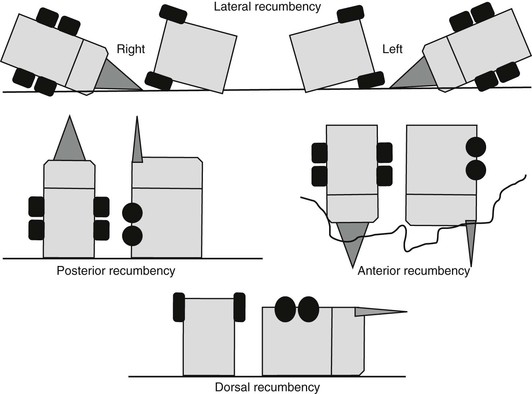

Wrecked horse trailers can end up lying on either side (most common) or in dorsal, posterior, or even anterior recumbency (Figure 1-1). In a slant-loaded trailer, lateral recumbency results in horses being tied to either the trailer roof or floor. In a forward-facing trailer, being tied to the front of the trailer limits the animal’s ability to right itself. Posterior recumbency, which is common in incorrectly hitched, two-horse, forward-facing trailers, often results in posteriorly recumbent animals facing one another and tied to the front of the trailer. Anterior recumbency is the least common trailer wreck; to end up in this position, the trailer would have been incorrectly hitched, allowing it to leave the roadway and catapult into a ravine or treed embankment. Because of impact on the face and neck and mirrored anterior recumbency of their bodies, horses rarely survive such accidents. Two other scenarios that can be expected to have high injury and mortality rates are trailer floor failure and trailers hit by trains. Animals are often in shock, have endured severe injuries and pain, and rarely have sufficient remaining muscle or tendon structures to enable surgical repair.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree