Daniel J. Burba

Extensive Skin Loss/Degloving Injury

Degloving injuries are wounds in which the skin becomes separated from its subcutaneous attachments. These injuries most commonly occur on the limb but can occur elsewhere, such as on the head or trunk. Limb degloving injuries arise when a limb becomes entrapped by, for example, a horse kicking through a stall wall or getting hung over a gate. Head degloving injuries may occur from animal bites (e.g., by a dog or alligator), whereas trunk degloving injuries occur from the body getting caught on a protruding object such as a gate latch (Figure 6-1). One concern relevant to degloving injuries is loss of skin or its blood supply at the time of injury. This is especially true of skin on the limbs, which has limited blood supply anyway and dies when the blood supply is damaged or lost. Loss of proximally originating blood supply to distally based skin flaps on horse limbs is of special concern because it can result in ischemic necrosis. If the periosteum is exposed or damaged, the wound must be treated quickly to prevent formation of a sequestrum. This chapter addresses the treatment of degloving injuries and other wounds that result in extensive skin loss.

Initial Triage

Triage of degloving wounds must include keeping the tissue moist until the wound can be treated more definitively, especially if the animal needs to be transported for further treatment. Desiccation of exposed bone can result in sequestrum formation, which is a common etiology of delayed healing of wounds on limbs of horses. Desiccation of the subcutaneous tissues also compromises viability and results in complications in healing. Triage of degloving wounds entails first removing as much gross debris from the wound as possible. The wound should then be explored with gloved hands to establish the extent of the injury and to explore for foreign bodies or bone fragments. Because injuries to adjacent synovial structures, tendons, and ligaments could affect the horse’s ultimate outcome, the extent of injury must be accurately determined and damage to adjacent structures addressed appropriately (see Chapter 186). After gross debris has been removed, a nonadherent wet-to-dry bandage is applied. This type of bandage is constructed by taking a thick, nonadherent absorbent pad such as a cotton combine sheet, soaking it in saline or a balanced electrolyte solution (BES), and applying it over the area. This is followed by application of an outer bandage. It is better to use isotonic saline or BES rather than hypotonic water, because the former two are more physiologic for exposed, still-viable cells. If gross debris cannot be removed effectively by thorough cleaning, the adherent wet-to-dry bandage will also aid in wound debridement. This is accomplished by applying a wetted thick disposable cotton sheet (adherent pad) directly to the wound. This is left in place for at least 12 hours. Dirt and debris wick into the bandage and will be removed when the bandage is changed. This is repeated until the wound can be effectively cleaned conventionally.

Cleaning of the Wound

General anesthesia may be required to clean and repair the wound. This depends on factors such as location of the wound on the body, extent of the injury, and cooperation of the patient. General anesthesia enables closer inspection of the wound, meticulous cleaning and debridement, and repair of the wound. It cannot be overemphasized that if the wound has a skin flap, the flap must be kept moist during preparation and wound closure. The wound can be cleaned by gently hand-scrubbing it with a disinfectant scrub and then rinsing with saline or preferably a BES. To help lift debris, the wound can be lavaged with a dilute disinfectant solution: chlorhexidine is preferred, but dilute povidone-iodine solution can also be used. The key to effective wound lavage is use of pressurized fluids; 70 psi is optimal, and higher pressures cause the subcutaneous tissues to become waterlogged. Lavage is continued until all gross debris has been removed.

Repair of the Wound

The wound should be closed as much as possible because closure will improve the cosmetic appearance as well as wound healing. Factors that affect wound closure include the extent of dead space, skin tension, and motion, all of which can increase the chance of dehiscence. Dehiscence is an especial concern in treatment of degloving wounds on the limbs: repair cannot be successful unless dehiscence is controlled.

Management of Dead Space in Large Wounds

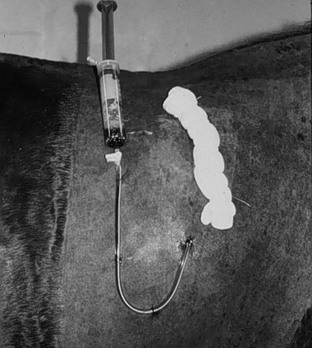

Dead space left under closed degloving wounds can result in development of a subcutaneous hematoma or seroma and disruption of the repair. Management includes obliteration of the dead space by use of walking sutures placed in the subcutaneous space or through-and-through sutures placed through the skin and anchored to underlying tissue. The latter are used primarily on large wounds on the trunk. On limbs, firmly placed compression bandages are very effective at collapsing the dead space. Placement of drains is another means by which blood or serum can be evacuated from dead space. Drains are categorized as either passive or active suction. A Penrose drain is the most common passive-type drain used in equine wounds, and in most cases, this is sufficient. Active suction drains, which are noncollapsible fenestrated drains,1 are much more effective in evacuating blood and serum from the dead space but require much more attention (Figure 6-2). As long as negative pressure (suction) is applied to the drain, bacteria cannot migrate up the drain, as can occur with passive drains. Regardless of the type, a drain should be placed at the most dependent aspect of the dead space and secured to the skin at the portal only. Because drains must be placed aseptically, local anesthesia can be used to assist in suture placement if the repair is not being undertaken with the horse under general anesthesia. A drain should not be left in place for more than 72 hours because of the increased risk for migrating infection and likely dehiscence.

Management of Tension Across a Wound Closure

In some cases of degloving injuries, there may be a substantial degree of retraction of the skin around the wound edges, which may make it difficult to close. This is especially true with injuries on the distal limb. A technique that can be employed to restretch the skin and bring the wound edges back into apposition is to apply countertraction. This can be accomplished by the use of towel clamps. After the wound has been cleaned and debrided and is ready for closure, the towel clamps are placed across the wound to pull the skin edges into apposition. If performed on a sedated patient, local anesthesia is needed before placement of the towel clamps (Figure 6-3). After the skin edges are brought back into apposition, tension on the wound closure can be reduced or eliminated by placing large tension-relieving vertical mattress sutures of 2-0 monofilament suture 2 to 4 cm from the wound edges. As the sutures are placed, the towel clamps are removed. It is important that, during the closure of these types of wounds, suture is not used as a primary means of pulling the wound edges together, especially by sawing back and forth to get the wound edges apposed. This will result in cut-through of tissue by the suture. After all of the tension-relieving sutures are placed, the actual wound edges are sutured.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree