CHAPTER 7 Tooth Resorption

Resorption of teeth can be a normal physiological process (exfoliation of primary teeth) or a pathological one. Causes of pathological resorption include pressure on the root (impacted tooth or expanding cyst or tumor), inflammation and infection (periodontal, apical, and internal resorption), orthodontic force, trauma (replantation), neoplasia, and after internal bleaching. There is a high incidence of tooth resorption (TR) in cats that are idiopathic, resembling the noncarious cervical tooth resorption seen in dogs, humans, and other species. These are unrelated to cervical lesions that are made by toothbrush abrasion. Although TRs in humans have been called many different terms they are often referred to as “invasive resorption,” “idiopathic cervical resorption,” and, more recently, “abfraction lesions.” The veterinary literature has also given them multiple labels over the years as is common with lesions and syndromes that are poorly understood. Resorption of dental tissue occurs through the action of odontoclasts regardless of the initiating cause, and similar tooth resorption occurs in many different species. Therefore, the term “feline” is inappropriately limiting and the term “odontoclastic” is redundant. For the purposes of this book we will refer to them simply as tooth resorption.

Feline Tooth Resorption—Clinical Presentations

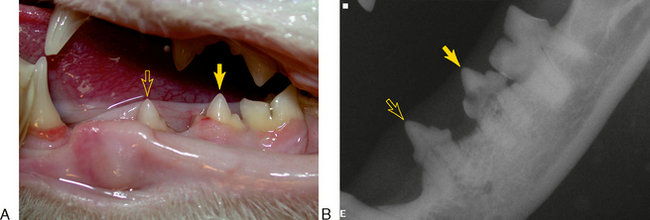

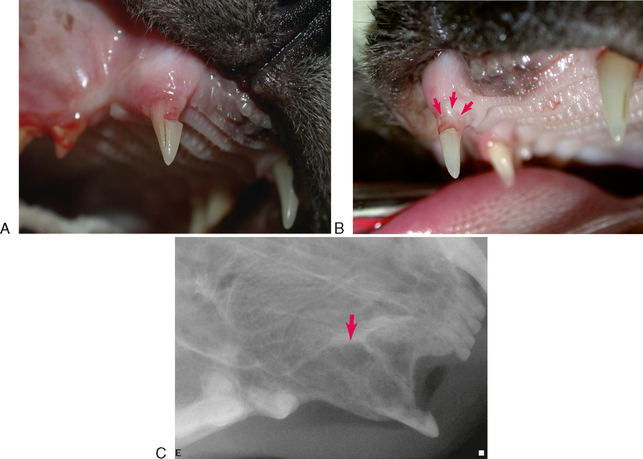

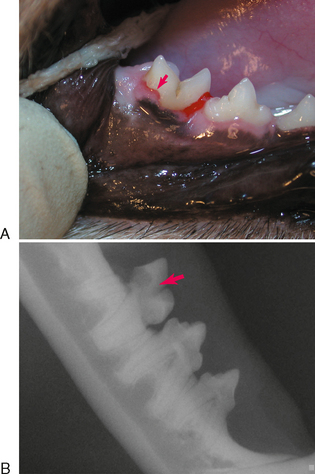

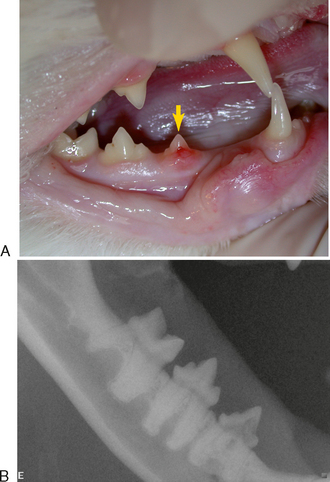

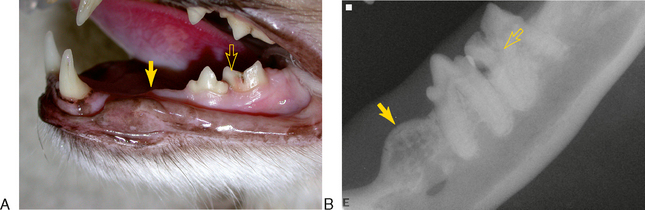

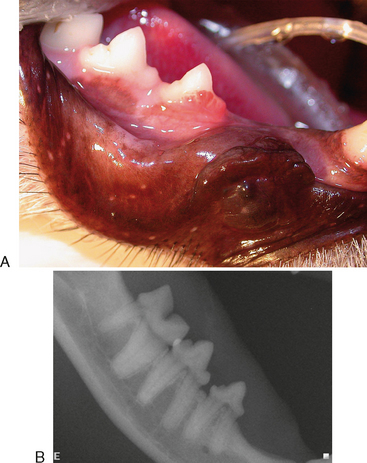

TRs that have no contact with the oral cavity (do not involve the enamel of the crown or are completely subgingival) are referred to as extraoral and may be present on clinically normal teeth. Extraoral TRs are not associated with discomfort in humans. Supragingival (intraoral) TRs, on the other hand, can cause dental discomfort in people and can be assumed to do the same in cats. Supragingival lesions are readily diagnosed clinically but require radiographs to determine the extent. Mild marginal gingivitis may be the only sign of an early lesion. Sites with localized inflammation should be investigated subgingivally with a sharp dental explorer. Lesions often appear as though the gingiva is growing up the crown of the tooth due to a tightly adherent gingival or granulomatous tissue (Figure 7-1). This upgrowth of tissue can be quite dramatic, particularly when it occurs on canine teeth (Figure 7-2). Lesions that extend above the gingiva have a sharp enamel margin that is readily identified with an explorer (Figure 7-3). Teeth with small clinical lesions frequently have extensive involvement that can only be identified radiographically (Figure 7-4). TRs can also appear as a missing tooth in an area with a raised alveolar marginal contour or as a pink spot on the crown at the site of internal resorption (Figure 7-5). Gingivitis in the furcation area of a multirooted premolar or molar tooth can mimic a site of resorption. Gingival hyperplasia can mimic the fibrogranulomatous tissue that often fills resorption defects (Figure 7-6). It is important to explore suspicious sites and radiograph the tooth.

TYPES

Radiographs of teeth affected with TRs show distinct changes. The roots of some affected teeth seem to “disappear” as they lose radiodense root tissue at a similar rate to the simultaneously occurring osseous repair, effectively making the roots appear to blend with the surrounding bone. The periodontal ligament and structural details are lost. Other TRs retain areas of normal radiodensity interspersed with radiolucencies caused by resorption and do not lose the detail of the periodontal ligament space and root structures in those areas not directly undergoing resorption. Areas of root resorption are often patchy, remaining radiolucent because the lost root substance is not replaced by reparative tissue. This type of TR also commonly demonstrates concurrent periodontal or endodontic disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree