Chapter 5 THE THORAX

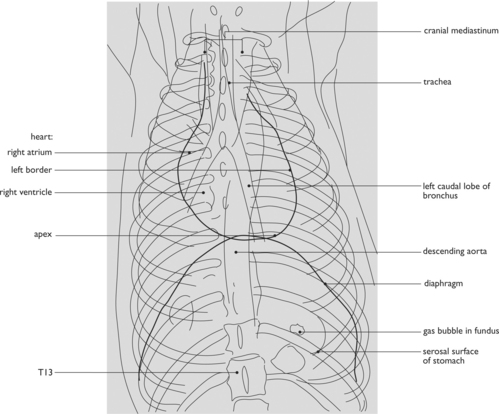

Clinically, the thorax is important because of the wealth of problems that may affect the heart, lungs and trachea, esophagus and diaphragm. The regions are presternal, sternal, cardiac and costal regions.

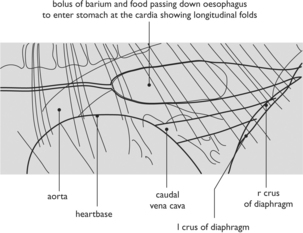

The thoracotomy can be used for all intrathoracic surgery. You have to cut mm latissimus dorsi, so be careful with the thoraco-dorsal nerve. It can be done in several ways. The lateral intercostal is usually used and gives good exposure and a good repair. Approximately one-third of the half of the thorax can be viewed from your incision. The incisions are made equidistant from the vertebrae to avoid the vessels and nerves. There is nowadays perceived to be no higher incidence of postoperative complications with median sternotomy than intercostal methods. In median sternotomy the manubrium or the xiphoid is left intact to aid stabilization of the ribcage when it is closed. Occasionally, transcostal is performed and the last method involves midline trans-sternal incision and this may be used for repair of the ruptured diaphragm where entrapment or adhesion of abdominal viscera within the thorax is anticipated. It is possible to remove a rib completely and then approach through the rib cage. Cranial thoracotomy requires incision through the M. scalenus and caudal thoracotomy through the external abdominal oblique and serratus ventralis muscles. Hiatus hernia of the esophagus is also repaired through a left thoracotomy or through a midline celiotomy (laparotomy). Pulmonary lobectomy for removal of a lung is usually for neoplasia, pneumothorax or emphysema, torsion of a lobe lung or foreign body infection can be carried out at the 5th intercostal space on either the left or right side or via a median sternotomy. For thoracolumbar disc protrusion, incision can be made over the intercostal muscle which is then transected and further incisions can be made to the spine.

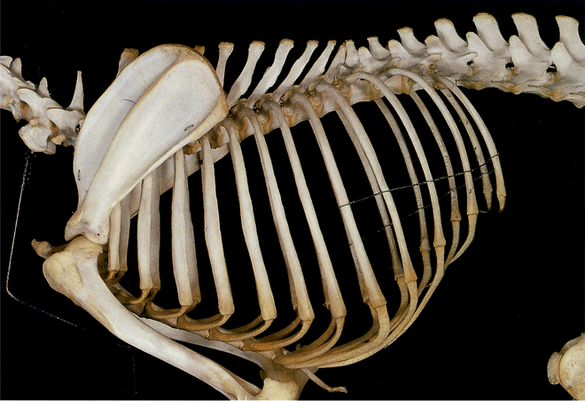

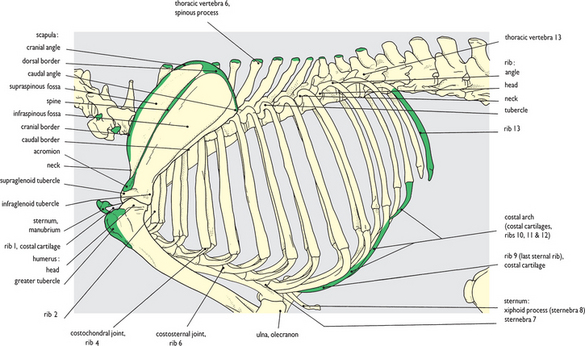

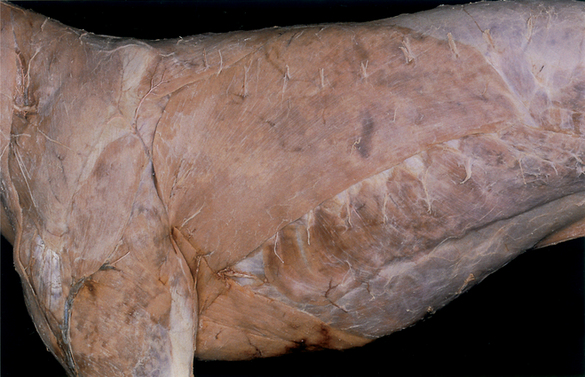

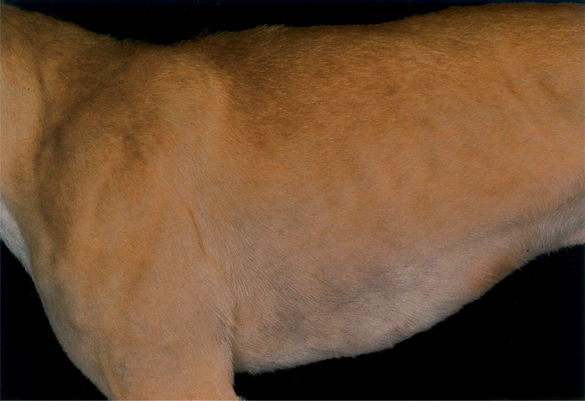

Fig. 5.1 Surface features of the shoulder and thorax: left lateral view. The palpable bony ‘landmarks’ and those muscles whose contours are clearly recognizable on palpation are indicated. In the normal standing posture the scapula and its associated muscles cover ribs 1 to 4 completely. The broken green lines indicate the position of structures as they are seen in subsequent dissections. It is extremely important to appreciate that these are not the normal positions in the live animal (see Fig. 1.3). In the live animal, the heart is more cranially placed and the cupola of the diaphragm may extend as far cranially as rib 6.

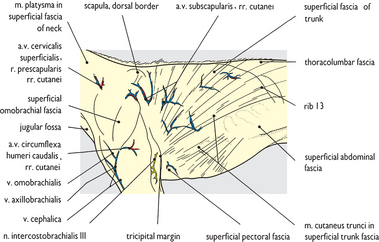

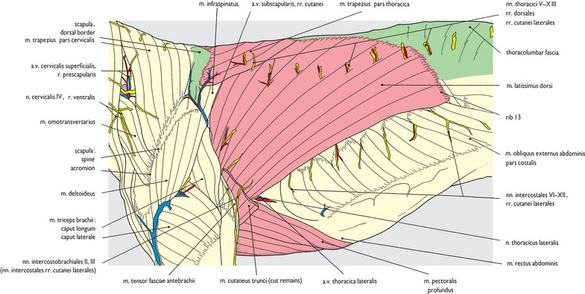

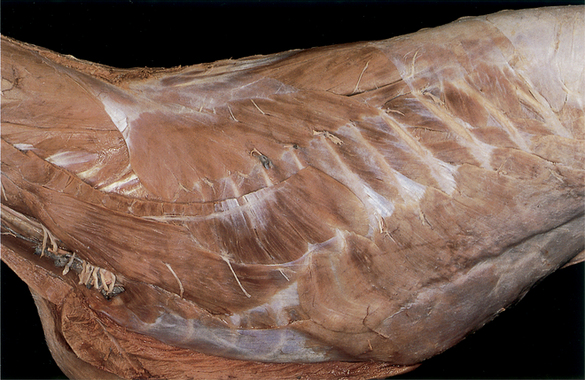

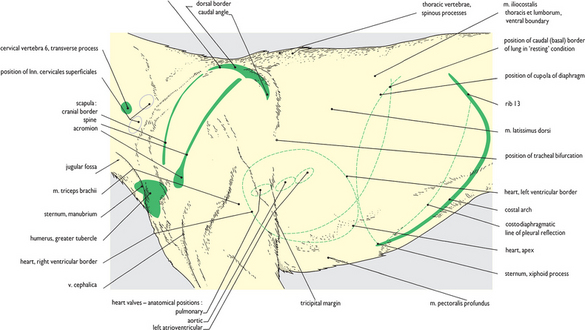

Fig. 5.9 Superficial structures of the shoulder and thorax (2) extrinsic forelimb muscles: left lateral view. Extrinsic muscles of the forelimb are exposed after removal of the superficial fascia and trimming of lateral cutaneous nerves. The basis of the caudal boundary of the upper arm, the tricipital margin, is clearly displayed. Deep thoracic fascia passes internal to the latissimus dorsi and pectoral muscles and medial to the upper arm, and forms the medial lining layer of the axilla (see Figs 3.43 and 5.82).

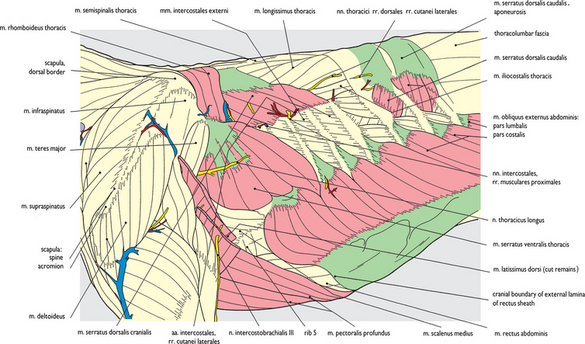

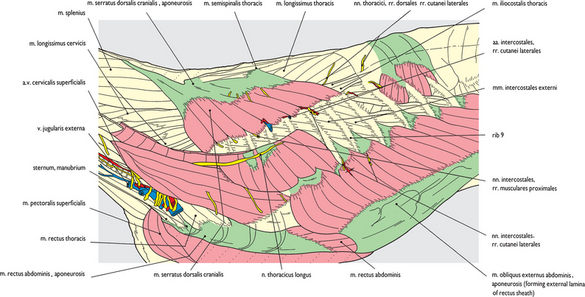

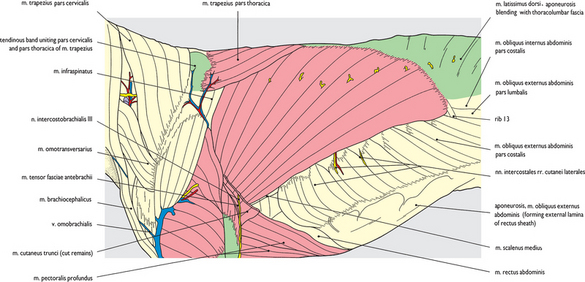

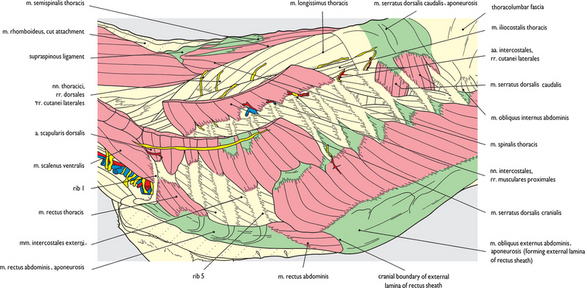

Fig. 5.13 Thoracic wall (4) external abdominal oblique muscle: left lateral view. The thoracolumbar fascia has been removed exposing the origin of the splenius muscle (see also Chapter 3), the supraspinous ligament and the spinalis and semispinalis thoracis muscles. Component parts of the scalenus muscle (dorsal and middle) which extended caudally onto ribs 2-6 have been removed leaving only the rib 1 attachment. This has exposed rib 1, parts of ribs 2-5 and the external intercostal muscles in the intervening intercostal spaces.

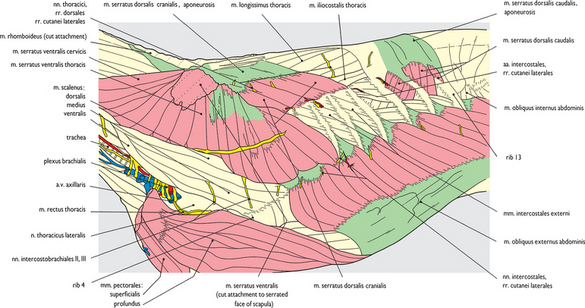

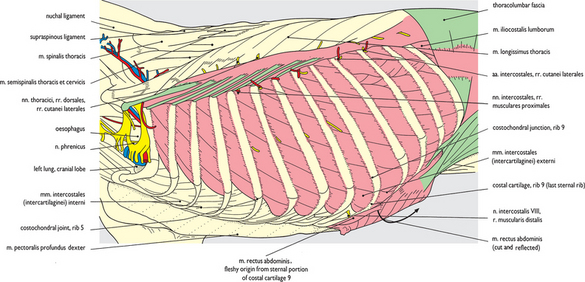

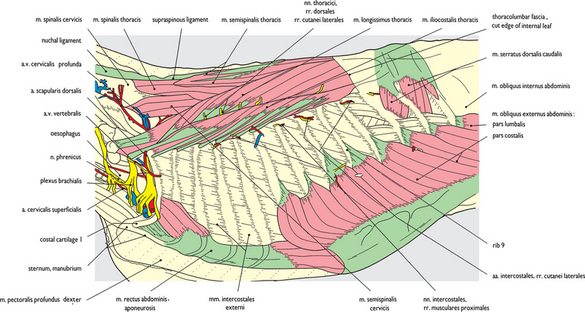

Fig. 5.14 Thoracic wall (5) longissimus and iliocostalis thoracis muscles: left lateral view. The rest of the ventral serrate and cranial dorsal serrate muscles and the component of the scalene muscle which attached to rib 1 have been removed. The overall extent of the ribcage is now becoming apparent with all 13 ribs at least partly exposed. Splenius and semispinalis capitis muscles have been removed from the neck (see Chapter 3) with much of the longissimus cervicis muscle. This has exposed the spinalis thoracis and semispinalis thoracis muscles, the longissimus thoracis extending cranially to cervical vertebra 6, and the iliocostalis thoracis muscle extending cranially onto cervical vertebra 7.

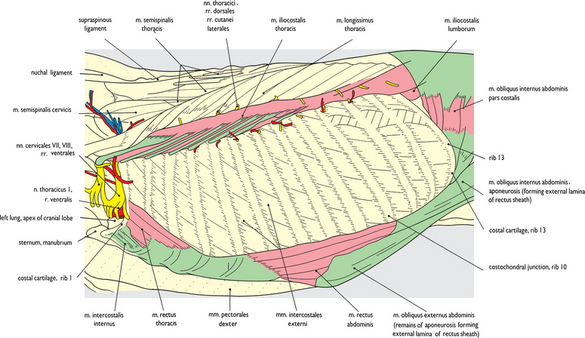

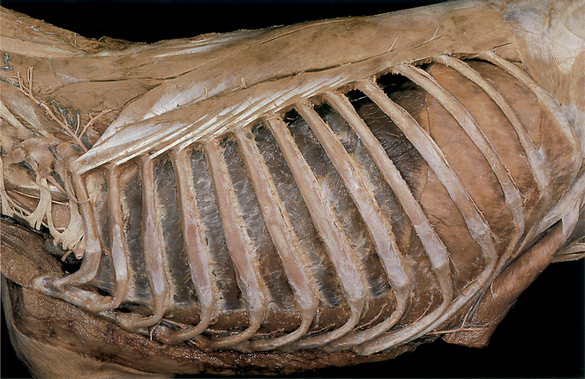

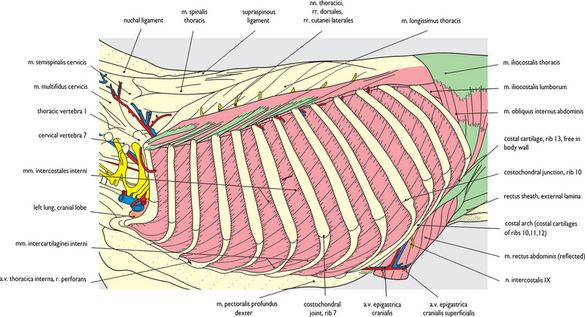

Fig. 5.17 Ribcage (2) internal intercostal muscles: left lateral view. The rectus abdominis muscle is fully reflected following the severance of its fleshy attachment (see Fig. 5.16). Exposed by this procedure are the costal arch, the continuation of the rectus sheath and the cranial epigastric vessels. The external intercostal muscles have also been removed from all of the intercostal and caudal interchondral spaces exposing the internal intercostal muscles.

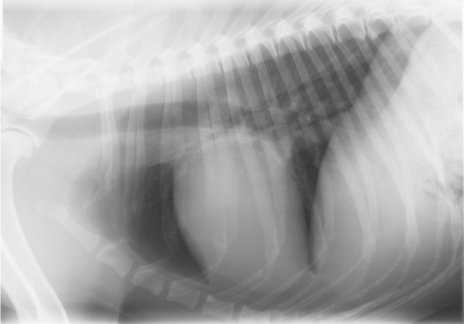

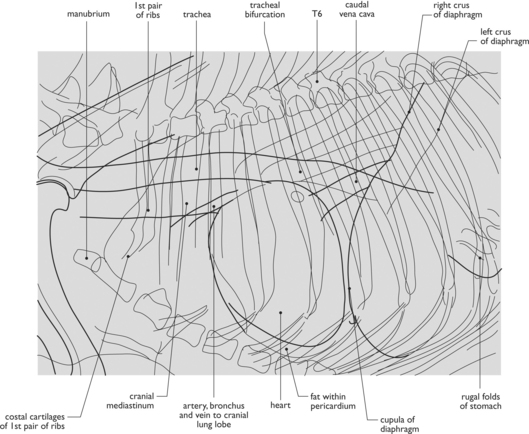

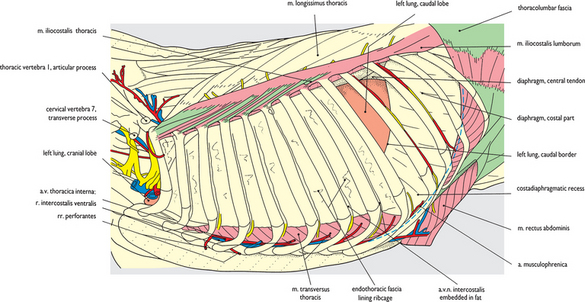

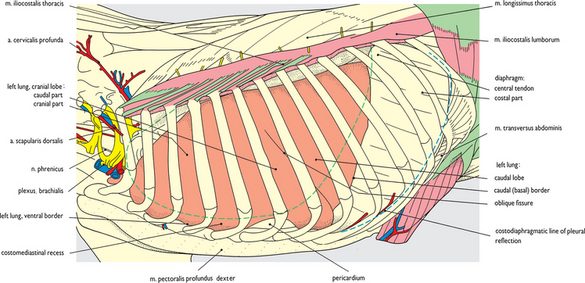

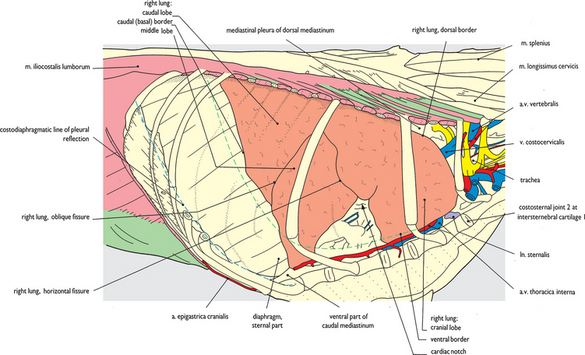

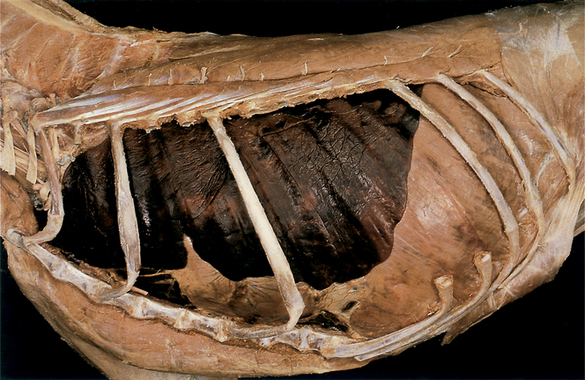

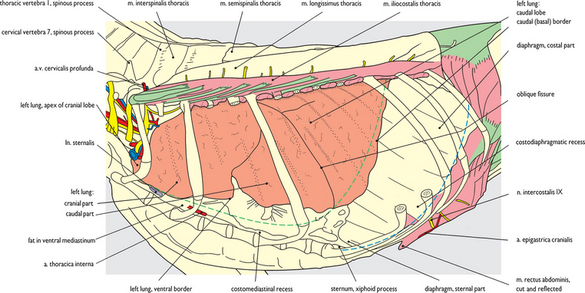

Fig. 5.21 Thoracic viscera in situ: left lateral view. Ribs 1, 3 and 6 are left in place to show the costal relationships of the viscera. The lungs in this specimen had hardened on fixation rather than becoming ‘waterlogged’ (unlike Fig. 5.19), presenting a more ‘normal’ outer contour. The costodiaphragmatic line of pleural reflection is indicated on this, and accompanying drawings by the broken blue line. It follows the attachment of the diaphragm to the ribcage from the midpoint of rib 13, through the distal part of rib 12 and the costochondral junction of rib 11 and follows the costal cartilages of ribs 10 and 9.

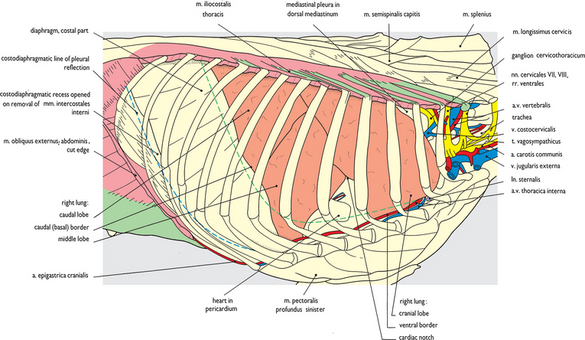

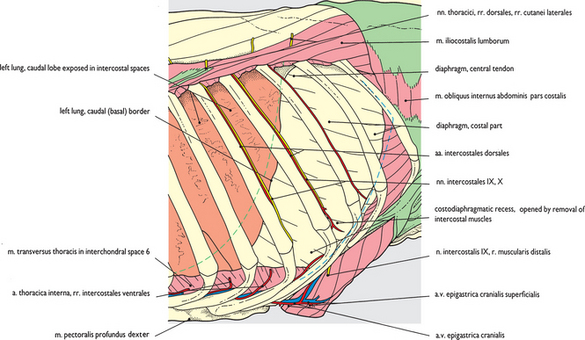

Fig. 5.23 Caudal ribs, costal arch, intercostal arteries and nerves: left lateral view. This is an enlarged view of the caudal end of Fig. 5.18. Intercostal arteries and nerves in intercostal spaces 9, 10 and 11 are displayed after removal of the endothoracic fascia. Continuations of intercostal nerves in spaces 10 and 11 penetrate between interdigitating fibers of the diaphragm and transverse abdominal muscle dorsal to the costal arch. Some internal intercostal muscles remain between the ribs caudal to the costodiaphragmatic line of pleura reflection.