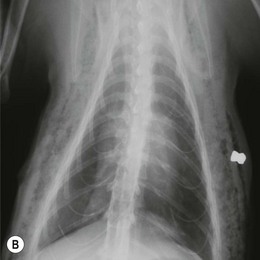

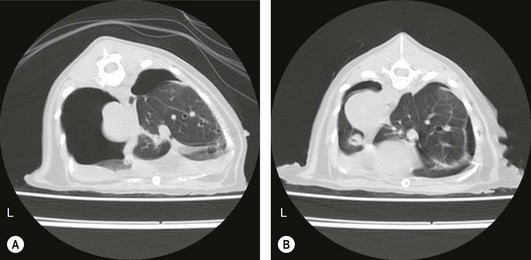

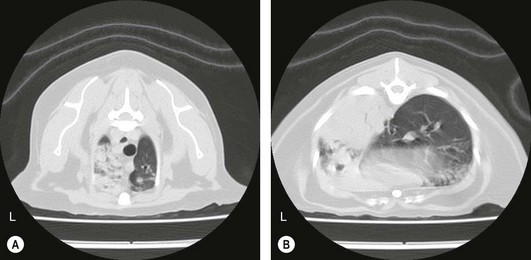

Chapter 41 A careful physical examination is imperative for animals presenting with clinical signs attributable to thoracic disease. Hyperpnea and tachypnea (Table 41-1) are common physical examination findings. Table 41-1 Definitions of common terms used to describe changes in breathing patterns Cats may often compensate for impaired respiratory function by becoming less active and owners may not notice clinical signs until they are severe. Cats are therefore more likely to be severely affected at first presentation than dogs with the same disease. Observation of the cat prior to physical examination should recognize those cats that are at risk of respiratory embarrassment during physical examination. When necessary, measures to prevent a respiratory crisis (such as providing oxygen support, but also interventions such as thoracocentesis) should never be delayed but should be undertaken in such a way as to minimize handling or restraint. Indicators of impending respiratory crisis are listed in Box 41-1. Careful observation of the pattern of respiration may help determine the type of thoracic disease present (Table 41-2). For example, pleural disease may result in short shallow respiration, whereas upper respiratory obstruction is more likely to result in a long deep inspiratory pattern. Thoracic auscultation also provides highly valuable additional information. Firstly, a basic assessment of whether or not there are audible breath sounds needs to be made and if breath sounds are absent, locating where the sounds are missing can rapidly help in identifying the type of pathology present. The use of gentle percussion must also always accompany auscultation to help identify fluid lines in cases of, for example, pyothorax. If breath sounds are auscultatable, then assessing whether they are appropriate for the respiratory effort of the patient is the next step. In a normal cat, breath sounds are quiet but audible, and they naturally become louder as respiratory rate increases e.g., with stress, exertion. However, increased respiratory rate does not normally generate abnormal breath sounds, so the identification of crackles or wheezes indicates the presence of pulmonary pathology and should always be investigated. It is also important to distinguish abnormal lower respiratory tract sounds from referred upper airway noise caused by upper respiratory tract disease. Table 41-2 Classification pathologic respiratory patterns Prior to any diagnostic or therapeutic intervention, and certainly prior to anesthesia, pre-oxygenation is recommended to improve oxygen delivery to tissues in patients with compromised respiratory function (Fig. 41-1). Whilst an oxygen cage or incubator provides the greatest fractional inspired concentration of oxygen, they are rarely available and do not allow concurrent physical examination. The practitioner may have to rely on mask or flow-by techniques, which only provide a minimal increase in fractional inspired oxygen compared to room air. Cats may find restraint, supplemental oxygenation, and diagnostic techniques distressing, leading to an increase in oxygen consumption and risk of further respiratory distress. Careful, continual assessment is therefore vital to ensure that attempted stabilization methods do not worsen the clinical status of the patient. Figure 41-1 Cat with an air gun pellet injury to the thorax. The cat is receiving supplemental oxygenation via a mask during clipping and cleaning of the wound. (© Alison Moores.) The choice of diagnostic test is determined by history and physical examination findings. If a pleural effusion is suspected, thoracocentesis should be performed, preferably after a brief ultrasound scan to confirm the presence of pleural fluid (Box 41-2, Fig. 41-2). Thoracocentesis can be both diagnostic and therapeutic and is often safer to perform than radiography, which may require manual or chemical restraint. Thoracic radiography can provide extremely useful information on the causal pathology of thoracic diseases (see Chapter 8), and should be undertaken following evacuation of pleural fluid or air and with minimal stress. In many circumstances a single dorsoventral radiograph may be sufficient to make a preliminary diagnosis, and it can be followed by a complete imaging study under sedation or anesthesia when the cat is more stable (Fig. 41-4). Thoracic radiography will indicate the presence or absence of pathology within the thoracic wall, lungs, and mediastinum, but it may be difficult to differentiate soft tissue structures and determine the exact location of disease. Ultrasonography is extremely useful for imaging patients that have pleural effusions, mediastinal disease, and lung lobe consolidation and in patients with mass lesions. Both ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) can be used to obtain fine needle aspirates and needle core biopsies, which can be submitted for cytology, histopathology, and bacteriologic/fungal culture and sensitivity (Fig. 41-5). The three-dimensional imaging techniques, especially CT, have made a significant impact on managing feline thoracic disease (Figs 41-6 and 41-7). CT is more sensitive in detecting metastatic pulmonary disease than radiography and localization of thoracic disease makes surgical planning and choice of thoracotomy approach easier. Due to the more accurate lesion localization afforded, more animals are likely to undergo lateral thoracotomy than median sternotomy if CT is available. Figure 41-4 (A) Lateral and (B) dorsoventral radiographs of the cat shown in Figure 41-1. A radiolucent tract is seen where the air gun pellet has entered on the right and it has stopped under the skin on the left side of the thorax. There is massive heterogenous subcutaneous emphysema in the soft tissues circumferentially around the thoracic cavity. Small air bubbles suggest associated subcutaneous hemorrhage. Interpretation of the lung parenchyma is difficult due to superimposition of subcutaneous emphysema. Cystic lesions in the right caudal lobe are consistent with penetration by the pellet; these lesions usually heal rapidly and were not seen on subsequent radiographs. (© Alison Moores.) Figure 41-5 Ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of a mediastinal mass in an anesthetized cat. Note the use of a heat/moisture exchanger (Thermovent). (© Alison Moores.) Figure 41-6 CT images of a cat that had presented with increased respiratory sounds and coughing. Two CT studies are shown (A) before and (B) after drainage of pneumothorax and these demonstrate the importance of thoracocentesis for improving lung expansion. (A) Bilateral pneumothorax. It is more marked on the left, with a collapsed lung lobe ventrally and air surrounding a left caudal lung lobe mass. There is moderate air present in the dorsal right hemithorax. (B) After drainage there is significant reduction in pleural air present, with increased expansion of the right middle, accessory and left cranial lung lobes. There is mediastinal shift of the left caudal lung lobe containing the mass and no air within this lung lobe. (© Alison Moores.) Figure 41-7 CT images of a cat that presented with a chronic cough. (A) Cross-sectional image of the cranial thorax showing a generalized, heterogenous, alveolar/bronchial infiltrate of the cranial part of the left cranial lung lobe, with a concurrent ill-defined nodular soft tissue infiltrate. On the right there is a nodular soft tissue lesion ventrally. (B) Cross-sectional image of the caudal thorax showing an ill-defined left caudal lung lobe soft tissue mass with the same ill-defined margin of heterogenous alveloar/bronchial infiltrate and nodular soft tissue infiltrate as seen in the previous CT image. Differential diagnoses include pulmonary neoplasia with pulmonary metastasis or severe inflammatory disease, which can be evaluated further by cytology or histopathology. (© Alison Moores.) The correct choice of which premedicant and induction agent to use is vital, to allow the induction of anesthesia with minimum stress, whilst avoiding excessive respiratory or cardiac depression.1 Intravenous induction, establishing a patent airway, and being able to ventilate if necessary, are all instrumental to safe induction of anesthesia. Intraoperative monitoring is also extremely important and should include serial monitoring of heart and respiratory rate, pulse oximetry, capnography, ECG, and core body temperature. Mechanical ventilation is required during thoracotomy, and also in laparotomies where the diaphragm is not intact, as opening the pleural space very significantly restricts effective natural ventilation. Mechanical ventilation may also be required prior to surgery when the underlying disease prevents effective chest excursions. Mechanical ventilators are easily applied to cats (Fig. 41-8), but careful manual ventilation is also acceptable. Care must be taken not to apply too much pressure during ventilation as this can cause lung damage. Figure 41-8 Mechanical ventilator. (© Alison Moores; The Nuffield 200 Ventilator is produced by Penlon Ltd, Abingdon, UK.) One of the major limiting factors to successful surgery is small patient size, but it is aided by the use of fine instruments. Additional instruments that will be helpful for thoracic surgery are listed in Box 41-3 (and see Chapter 13). These include vascular clamps for the control of hemorrhage from large vessels, such as the pulmonary artery, as well as diathermy for hemorrhage from smaller vessels.

Thoracotomy

Diagnostic approach to the cat with impaired respiratory function

Term

Definition

Dyspnea

Subjective experience of breathing discomfort

Hyperpnea

Fast and/or deep breathing

Tachypnea

Increased breathing rate, usually shallow

Hyperventilation

Increased breathing that causes CO2 loss

Respiratory pattern

Disease examples

Prolonged inspiratory phase ± stridor

Upper respiratory tract disease, e.g., laryngeal obstruction, tracheal obstruction/stenosis

Expiratory effort, crackles on auscultation

Pulmonary disease, e.g., inhalation pneumonia

Short shallow respiration, decreased lung sounds on auscultation, hyporesonant percussion

Pleural disease with effusion, e.g., pyothorax

Wheezing on auscultation

Lower airway disease, e.g., feline bronchial disease

Diagnostic imaging for thoracic disease

Preparation for thoracic surgery

Thoracotomy