Chapter 52Thoracolumbar Spine

Back problems are a major cause of altered gait or performance (see Chapters 50, 51, and 97). Both identification and documentation of vertebral lesions are difficult in horses; therefore treating back pain is a challenge for the equine clinician. The equine back is a large area covered by thick muscles. Therefore assessment of the bony elements is limited. Every joint in the thoracolumbar region has restricted mobility; therefore detecting changes in restricted movement when the horse is working is difficult. Diagnostic imaging of the thoracolumbar region is also limited, and radiological assessment requires special equipment. Specific treatment of back pain can only be performed after complete identification of the site and nature of the lesions.

Anatomy and Function

Joints

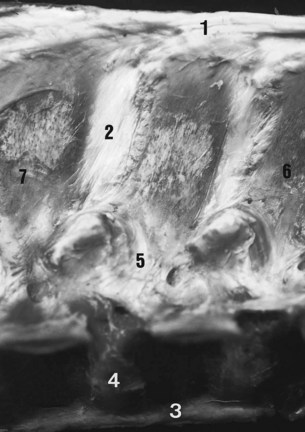

Stability of the thoracolumbar vertebrae is provided by the supraspinous and interspinous ligaments, the joints between the cranial and caudal articular processes (the facet joints), the joints between the vertebral bodies, and the dorsal and ventral longitudinal ligaments. Stability of the spinous processes is provided by the supraspinous and interspinous ligaments (Figure 52-1). These ligaments are wider and more elastic in the cranial and middle thoracic areas, permitting more movement than in the caudal thoracic and lumbar regions.

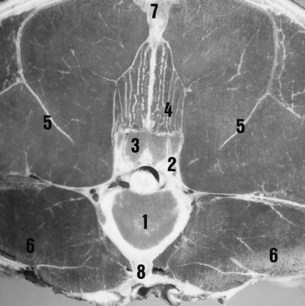

The caudal and cranial articular processes articulate via synovial intervertebral articulations (the facet joints). At the base of the spinous processes these joints are symmetrically placed on each side of the median plane (Figure 52-2). These are typical synovial (diarthrodial) joints with articular cartilage, a closed synovial cavity containing synovial fluid, a synovial membrane, and a fibrous capsule. They have a single flat articular facet in the cranial thoracic area (up to T12) and two angulated articular facets between T12 and T16. From T17 to S1 the articular facets are congruent, with a cylindrical shape aligned on a paramedian axis. These regional variations are correlated with the limited mobility of the lumbar spine and the wider range of movement in the thoracic region, including flexion and extension in the median plane, lateral flexion in the horizontal plane, and rotation. The vertebral bodies are stabilized by joints composed of a fibrous intervertebral disk and two longitudinal ligaments. The ventral longitudinal ligament is replaced by the longissimus cervicis muscle in the cranial thoracic area. The dorsal longitudinal ligament is located in the vertebral canal and adherent to the dorsal border of each intervertebral disk.

Muscles

The vertebral column is moved by wide muscles (Figure 52-3). The strong epaxial muscles, located dorsal to the vertebral axis, have an extensor effect when contracted bilaterally. Unilateral contraction induces lateral flexion and contributes to rotation of the vertebral column. Electromyographic studies show that the epaxial muscles limit flexion and stabilize the vertebral column during the suspension phase at the trot.1,2

The epaxial muscles include the following:

Diagnosis of Back Pain

Back pain may also be manifest by abnormal behavior, for example, bucking (see page 992).

Physical Examination

Mobilization

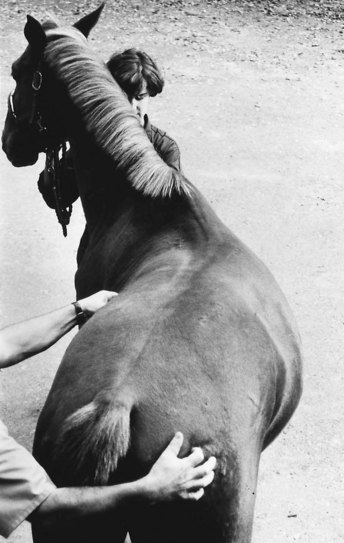

Stimulation of movement of the thoracolumbar spine (Figure 52-4) is important to assess the amount of movement tolerated by the horse and any signs of pain, such as flexion of the limbs, alteration of facial expression, tension of the back muscles, movement of the tail, and alteration of behavior (kicking, rearing, bucking, and grunting).

The following protocol is recommended:

The clinician should try to determine which movements are restricted or not tolerated so as to determine potential sources of pain. These movements can be induced by skin stimulation of the dorsal and lateral aspects of the trunk and hindquarters. Although some horses respond to soft digital stimulation, in others a stronger stimulus is required, for example, using the tips of a pair of artery forceps. Firm stroking with a hard instrument displaced craniocaudally and inducing spectacular wide extension and flexion movements may lack sensitivity and specificity in determining the site of back pain, but firm stroking may be necessary in extremely stoical cob-type horses to induce any movement. A normal, relaxed horse is able to flex and extend the thoracolumbar spine smoothly and repeatedly. The degree of movement reflects in part the type of horse. Cob-type horses naturally tend to have much more restricted movement than TBs or Warmbloods. The clinician will find it useful to keep one hand resting on the midback region during these maneuvers to detect induced muscle spasm or abnormal cracking of the muscles or ligaments (a crepitus-like feeling as the epaxial muscles or ligaments contract and relax). Further descriptions of assessment of thoracolumbar movement are provided in Chapter 51. Pressure algometry has been used to more objectively quantify back pain.8,9

Examination during Movement

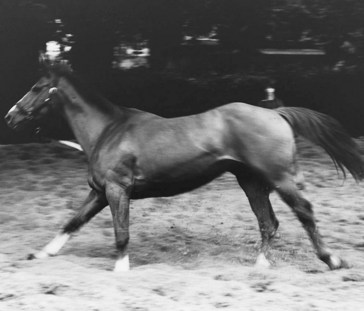

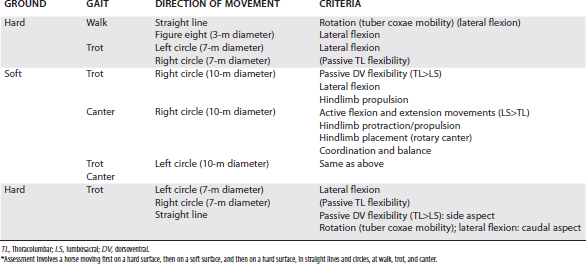

Evaluation of the horse moving at walk, trot, and canter is essential to assess whether pain is present and to identify functional disorders, such as limitation of regional intervertebral mobility (Figure 52-5). The clinician should always bear in mind that impinging spinous processes can be present asymptomatically. Therefore the clinical significance of impinging spinous processes should not be overinterpreted, unless clinical signs of back pain are evident. The horse should be assessed moving in straight lines and in small circles at a walk and trot on a hard surface and moving at a trot and canter on the lunge to determine whether any reduction of back mobility is apparent (Table 52-1).

Examination of the Horse Being Ridden or in Harness

The presence and the degree of back pain may be underestimated unless the horse is evaluated under its normal working conditions, that is, ridden or in harness. The influence of a rider on mobility of the horse’s back has recently been quantified.16 The clinician should watch carefully as the tack or harness is applied, particularly as the girth is tightened. However, the clinician should bear in mind that cold-back behavior (see Chapter 97) is not necessarily a reflection of back pain, although it may be. The fit of the saddle for the horse and the rider should be evaluated. Back mobility,3 the movements that the horse finds difficult, and the horse’s attitude toward work should all be assessed (see Chapter 97). The clinician should pay attention also to the observations of the rider because the horse may feel considerably worse than it appears. The rider may describe lack of hindlimb power, lateral stiffness of the back to the left or right, unwillingness of the horse properly to take the bit, or loss of fluidity in the paces. The rider may complain of back pain induced by riding the horse.