CHAPTER 14Therapy for Mares with Uterine Fluid

Reduced fertility associated with fluid accumulation has been recognized for many years in broodmares. This subfertility is due to an unsuitable environment within the uterus for the developing conceptus, and in some instances the ensuing endometritis persists and causes early regression of the corpus luteum. The term endometritis refers to the acute or chronic inflammatory process involving the endometrium. These changes frequently are the result of microbial infection, but they also can be due to noninfectious causes. The objective of the veterinary surgeon and the stud farm owner or manager should be to produce the maximum number of live, healthy foals from mares mated during the previous season. One of the main obstacles to this goal is susceptibility in individual mares to persistent acute endometritis, manifested as fluid accumulation in the uterus after mating.

Persistent mating-induced endometritis has come to be recognized as a major reason for failure of mares to conceive. Persistent sperm-induced inflammation may be a more important cause of infertility in susceptible mares than infectious endometritis.1

PATHOGENESIS

The Inflammatory Response to Semen

Semen is deposited directly into the uterus when mares are bred by either natural service or artificial insemination. This means that bacterial and seminal components, as well as debris, contaminate the uterus, which results in uterine inflammation. It was previously thought that the inflammatory response to breeding was due to bacterial contamination of the uterus at the time of insemination. It is now accepted that the spermatozoa themselves, rather than bacteria, are responsible for the acute inflammatory response in the equine uterus after insemination.2 Spermatozoa are transported rapidly to the oviducts, but only a small number actually reach the site of fertilization. The greater part of the ejaculate remains in the uterus, where it induces an acute inflammatory reaction.

Kotailen et al3 showed that the intensity of the reaction was dependent on the concentration and/or volume of the inseminate: Concentrated semen (frozen semen) induced a stronger inflammatory reaction in the uterus than that observed for fresh or extended semen. The inflammatory reaction of the uterus is not different for live or for dead spermatozoa.4

Work by Nikolakopoulos and Watson5 found that the number of uterine neutrophils (polymorphonuclear leukocytes [PMNs]) was greater when smaller numbers of sperm were infused. Because the volumes used in this study were larger, however, it may be that a significant amount of inseminate was lost via cervical reflux. In addition, the mares were not sampled for PMNs until 48 hours after insemination. It is likely that the inflammatory reaction was well past its peak by then.6,7

That the intensity of the inflammatory response following insemination depends on the sperm themselves, rather than on any extender, was the conclusion of Parlevliet and her co-workers,8 who measured the inflammatory response after insemination with raw semen, extended semen, and various extenders.

Seminal plasma is the fluid portion of the ejaculate and suspends the cells present in semen. Seminal plasma improves sperm transport either directly or by protecting the sperm from phagocytosis while in the uterus, thereby improving survival time. Seminal plasma is rich in oxytocin and prostaglandins, both of which cause uterine contractions. The precise role of seminal plasma in sperm transport in the horse is not known. Seminal plasma prolongs sperm life within the uterus because it suppresses PMN chemotaxis and phagocytosis of sperm. The mechanism is thought to involve more than simply complement inactivation.9,10

Evidently, then, seminal plasma modulates the inflammatory response to spermatozoa. A reduction in the inflammatory response after insemination can be expected to have both positive and negative effects. Any suppression of phagocytosis will reduce the elimination of sperm but also of bacteria. The amount of fluid produced after insemination may be reduced. Seminal plasma has a low buffering capacity, and in a freshly collected ejaculate, by-products rapidly accumulate in seminal plasma as a result of the high metabolic activity of the sperm cells. During freezing of sperm, seminal plasma is removed. This may be why the inflammatory response is greater with frozen/thawed semen. The increased response also may be due to the high sperm concentration.3 Recently, it has been reported that seminal plasma decreases uterine contractility and increases the inflammatory response of the uterus to semen.11 Thus, the evidence for the role seminal plasma plays in inflammation within the uterus of the mare is conflicting.

The first inflammatory cells to enter the uterus are PMNs, observed in the uterus within 30 minutes after insemination.12 The equine uterus produces fluid that has chemoattractant properties for PMNs.6 Complement is thought to be the crucial component that serves as a chemoattractant for PMNs, although other products may serve as chemoattractants.6,7 It is now believed that spermatozoa initiate chemotaxis of PMNs through activation of complement,13 suggesting that a transient uterine inflammation following insemination is physiologic and serves to clear the uterus of excess spermatozoa, seminal plasma, and contaminates associated with insemination. Damaged sperm may be more readily phagocytosed by PMNs. In normal mares, the inflammation peaks at approximately 10 to 12 hours and subsides appreciably within 24 hours after insemination.

If the endometritis persists beyond day 3 or 4 of the luteal phase, however, in addition to being incompatible with embryonic survival, the premature release of the prostaglandin PGF2αresults in luteolysis with a rapid decline in progesterone and an early return to estrus. Mares in which this occurs are referred to as susceptible, and they develop a persistent endometritis.6 The concept of susceptibility to endometritis was first suggested by Farrely and Mullaney,14 who stated that infective endometritis is essentially the failure of an individual mare to limit the uterine and cervical microflora to a nonresident type. At the same time, Knudsen15 reported the discrete collection of fluid in permanent ventral dilatations at the base of one or (rarely) both horns of the uterus that could be palpated per rectum. Hughes and Loy16 developed the concept of susceptibility to endometritis and confirmed that resistant mares could eliminate induced infection without treatment, whereas susceptible mares could not. In general, reduced resistance to endometritis is associated with advancing age and multiparity.

Susceptibility to endometritis is not an absolute state, because failure of uterine defense mechanisms need only slow the process of eliminating infection. In the practice situation, a wide range in degrees of susceptibility to endometritis is seen, and it must not be thought that mares can be neatly classified as either resistant or susceptible.17 Studies on immunoglobulins, opsonins, and the functional ability of PMNs in the uterus of susceptible mares have not confirmed the presence of an impaired immune response (see the review by Allen and Pycock18). Evans et al19 first suggested that reduced physical drainage may contribute to an increased susceptibility to uterine infection. The physical ability of the uterus to eliminate bacteria, inflammatory debris, and fluid is now known to be the critical factor in uterine defense. It is a logical conclusion that any impairment of this function—that is, defective myometrial contractility—renders a mare susceptible to persistent endometritis.20–22 The reason for this defective contractility in susceptible mares is not known. It has been suggested that the regulation of muscle contraction by the nervous system may be impaired.23

The resulting fluid accumulation also could be due to failure to drain via the cervix or to decreased reabsorption by lymphatic vessels. Lymphatic drainage potentially may play an important role in the persistence of postbreeding inflammation, and it is interesting that lymphatic lacunae (lymph stasis) are a common finding in endometrial biopsy specimens taken from susceptible mares.24,25

Other factors can be involved in a delay in uterine clearance. In older mares that have had several foals, the uterus may have dropped ventrally within the abdomen. Such mares can have a delay in uterine clearance.26

An adequate cervical opening is vital to allow drainage, and any failure of the cervix to dilate can cause fluid accumulation (see Chapter 21). This failure of the cervix to open is particularly relevant in the case of the older mare in general and the older maiden mare in particular, leading to the term “old maiden mare syndrome.” Recognition and appropriate management of the older maiden mare are particularly important because a susceptibility to postbreeding endometritis is common in such mares even though they have never been bred before. Mares that have had a showjumping or dressage career often may not be presented to be bred until they are in their teens, and such mares can be very difficult to get in foal.

Older maiden mares have some common characteristics that resemble a syndrome. Endometrial biopsy samples reveal glandular degenerative changes and stromal fibrosis (endometriosis) as an inevitable consequence of ageing even in mares that have not been bred.27 Another common characteristic is presence of uterine fluid. The older maiden mare often has an abnormally tight cervix that fails to relax properly during estrus, so that fluid is unable to drain and then accumulates in the uterine lumen.28 In many instances, this fluid tests negative for bacterial growth and presence of PMNs. Once the mare is bred, the fluid accumulation will be aggravated as a result of poor lymphatic drainage and impaired myometrial contraction compounded by the cervical tightness. The amount of intrauterine fluid will vary in individual mares, ranging from a few milliliters to greater than a liter in extreme cases. Recently, endometrial vascular degeneration also has been suggested as a contributing factor in delayed uterine clearance.29 To maximize the fertility of these mares, it is vital that the veterinarian be aware of the possibility of this type of uterine and cervical pathology. All too often, owners assume that the fertility of these mares is comparable to that of younger maiden mares; one of the most important aspects of breeding the old maiden mare is to make the owner aware of the increased risk of problems. These mares must be regarded as highly susceptible and managed accordingly.

DIAGNOSIS

Identification of the Fluid-Producing Mare

Identifying the susceptible mare can be difficult because only subtle changes may be present in the uterine environment, not readily detected by current diagnostic procedures. Many mares show no signs of inflammation before mating but will fail to resolve the inevitable endometritis that follows mating. Response to bacterial challenge has been used in a research setting. Scintigraphic and other methods based on charcoal clearance have been used to make an accurate diagnosis of a clearance problem in a mare,22 but such methods are difficult to apply in practice. History of repeat breeding and/or fluid accumulation at the time of breeding is perhaps the most useful indicator of susceptibility to mating-induced endometritis in an individual mare.

Detection of Intraluminal Uterine Fluid Using Transrectal Ultrasound Imaging

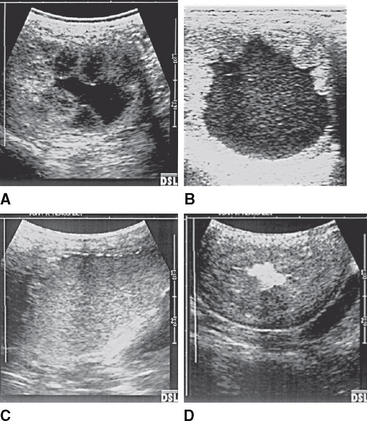

Ultrasonographic examination to detect uterine luminal fluid (Figure 14-1) has proved useful to identify mares with a clearance problem and is the most useful technique in practice. The presence of free intraluminal fluid before breeding strongly suggests susceptibility to persistent endometritis.30 Excessive production of fluid due to glandular alterations, rather than a failure of lymphatic drainage, has been postulated to cause intrauterine fluid accumulation.31 It is currently not known for certain, however, whether the fluid accumulates as a result of excess production, delay in physical clearance via the open cervix, or decreased reabsorption by lymphatic vessels; a combination of all three mechanisms may well be involved.

Since the first description of the identification of collections of small volumes of intrauterine fluid using ultrasound imaging, which could not be palpated per rectum,32 general awareness of the frequency of this abnormality has increased. The detection of uterine fluid during both estrus and diestrus has been reported.33,34 Endometrial secretions and the formation of small volumes of free fluid may be associated with the same mechanism responsible for normal estral edema formation. In many instances, the uterine luminal fluid that accumulates before mating is sterile and contains no neutrophils.30 The importance of these sterile fluid accumulations is that although initially sterile, the fluid may act as a culture medium for bacteria that gain entry to the uterus at mating and also may be spermicidal.35

The amount of fluid that should be considered significant is not clear, and it may be that quantity is more important than nature, particularly for fluid appearing during estrus. Brinsko et al36 concluded that the presence of more than a 2-cm depth of fluid during estrus was a predictor of susceptibility. The significance depends to some extent on when during estrus the fluid is observed: Fluid detected early in estrus may disappear subsequently when the mare is further advanced in estrus and the cervix relaxes more. Small volumes of intrauterine fluid during estrus do not affect pregnancy rates in mares, in contrast with larger (>2 cm in depth) collections of fluid.30 Mares that are susceptible to endometritis demonstrate greater accumulation of fluid than that observed in resistant mares.

In general, if greater than a 1-cm-depth of fluid is present during estrus, some attempt should be made to remove this fluid before breeding using oxytocin. If the depth is greater than 2 cm, the fluid is drained and may need to be investigated for the presence of inflammatory cells and bacteria. The mare may then need to undergo large-volume uterine lavage. Visualization of intrauterine fluid on ultrasonography performed later than 18 hours after breeding is diagnostic of defective uterine clearance in the mare. Intrauterine fluid during diestrus is indicative of inflammation and is associated with subfertility related to early embryonic death and a shortened luteal phase.37

Intraluminal uterine fluid can be graded I to IV according to the degree of echogenicity (Figure 14-2). The more echoic the fluid, the more likely the fluid is contaminated with debris including white blood cells. Cellular fluid can appear relatively anechoic, however, so care is needed in interpretation. Inspissated pus can be so echoic that it is overlooked. It may be that the actual character of the fluid and the ultrasonographic appearance are not as closely linked as was once thought.

Ultrasonographic appearance may be proportional to the size and concentration of particulate matter within the fluid, rather than the viscosity of the fluid; for example, purulent exudates can appear nonechogenic. Air has hyperechoic foci (Figure 14-3), and fluid with air bubbles appears cellular. Urine in the bladder can appear echoic, despite being a watery liquid (Figure 14-4).

TREATMENT OPTIONS FOR MARES WITH FLUID ACCUMULATION

The aim of treatment for mares with fluid accumulation should be to assist the uterus to physically clear the normal inflammatory by-products of the response to breeding.38–41 Because within 4 hours of mating, the spermatozoa necessary for fertilization are present within the oviduct, and because the embryo does not descend into the uterus for approximately 5.5 days, treatment may be safely given from 4 hours after mating until 2 days from ovulation, provided that isotonic solutions are used. Progesterone concentrations rise rapidly following ovulation in the mare, however, and it is preferable to avoid treatment involving uterine interference beyond 2 days after ovulation. Both coitus and artificial insemination can be a source of uterine contamination; it is well known that spermatozoa themselves are responsible for initiating a marked inflammatory response leading to a persistent endometritis in susceptible mares.12 Susceptible mares, therefore, may be bred only once per estrus, regardless of whether natural mating or artificial insemination is used. If repeated breedings are necessary, uterine lavage should be performed after each mating.

Uterine Lavage

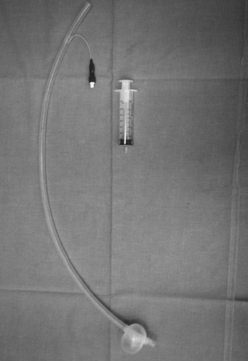

Recognition of the importance of the mechanical evacuation of uterine contents accounted for the introduction of large-volume uterine lavage. The technique involves infusion of 2 to 3 liters of previously warmed (to 42° C) sterile physiologic (buffered) saline or lactated Ringer’s solution into the uterus via a catheter that has been retained within the cervix via a cuff. The fluid is then siphoned out of the uterus by gravity flow. The most convenient device is a large-bore (30 French), 80-cm autoclavable equine embryo flushing catheter (EUF-80, Bivona, Ind) (Figure 14-5). The cuff is useful to effectively seal the internal cervical os. The catheter should be inserted only after thorough cleansing of the perineum (Figure 14-6). The rationale for such an approach includes the following considerations:

Figure 14-5 Large-bore (30 French) embryo flushing catheter, 80 cm in length. Note the inflated cuff.

The saline is infused by gravity flow 1 L at a time, and the washings are inspected to provide immediate information concerning the nature of the uterine contents. The lavage should be repeated until the fluid that is recovered is clear (Figure 14-7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree