CHAPTER 17Management Regimens for Uterine Cysts

Uterine cysts are diagnosed clinically either during routine examination per rectum of the internal genital tract if of sufficient size by palpation, or by ultrasonography if smaller. There is controversy over the effect of uterine cysts on fertility, and there are a number of different recommended treatments indicating the inability of any one treatment to be consistently successful. Almost invariably, uterine cysts are associated with some degree of chronic degenerative change within the endometrium referred to as endometrosis.

ENDOMETROSIS

Endometrosis refers to the described wide range of degenerative histopathologic characteristics of the endometrium in mares.1 The condition is degenerative and lacks the typical features of active inflammation. Historically the term endometritis was and often still is indiscriminately used for this condition. However, the use of the modifying suffix “-itis” in association with this pathologic condition is felt to be misleading and inaccurate. Infiltrates of lymphocytes, plasmacytes, and macrophages are the predominant cell types observed in the submucosal periglandular endometrial tissues of such mares. Endometrosis is a feature of uterine “wear and tear” that develops during a mare’s advancing reproductive lifetime. Its development is age related, but the age of onset varies between individual mares. The major histopathologic changes that characterize endometrosis are considered to be fibrosis, lymphatic stasis, uterine sacculation, transluminal adhesions, and glandular or lymphatic cysts.2,3 Cystic glandular changes are often observed in endometrial biopsy specimens from older mares.4 These are thin walled and contain fluid with large numbers of lymphocytes, suggesting that they may be due to stromal fibrosis causing obstruction of uterine glands. Glandular duct obstruction is postulated to arise by one of several mechanisms: (a) a strangling effect produced by periglandular fibrosis; (b) decreased myometrial tone and peristaltic activity associated with either prolonged anestrous or age-related changes; and/or (c) epithelial hypertrophy, one of the first responses to periglandular fibrosis observed in the equine endometrium.

Reliable and specific treatments have not been described that can permanently alter or reverse the course of endometrosis. Treatments that have been described attempt to induce superficial endometrial inflammation, necrosis, and tissue loss in the hope that the tissue that regenerates is in a better state to support any subsequent pregnancy.5–7 A few of the treatments studied in critically controlled settings have shown to be of some benefit in improving endometrial histomorphologic architecture in the posttreatment evaluation period. These therapies also have the potential for inducing irreversible damage to the urogenital tract of mares treated if treated too vigorously or if used inappropriately. They must therefore be used in a cautious and controlled manner. Overly aggressive application of mechanical modalities, such as endometrial curettage,8 or too caustic a chemical irritant may induce superficial mucosal, and possibly submucosal, necrosis and potentially lead to the development of intrauterine, cervical, and/or vaginal adhesions. The long-term effects of such therapies have received little study. Whether or not there is increased endometrial fibrosis in mares years after receiving such treatments is unknown. With all such therapies, it is cautioned that they are to be reserved for use in mares that have otherwise failed to respond to more traditional intrauterine treatments. It is of the utmost importance in each case to mate treated mares using a breeding management technique to minimize uterine contamination and optimize her chances for conception.9

UTERINE CYSTS

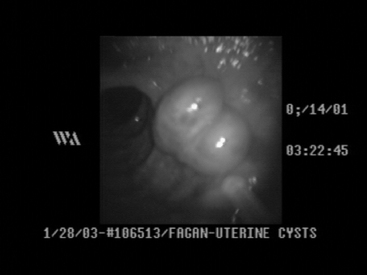

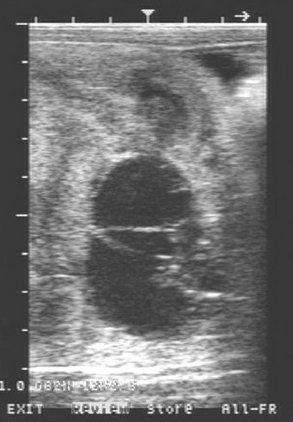

There are two distinct types of uterine cysts recognized. Endometrial glandular cysts are smaller (5 to 10 mm) and usually are the result of periglandular fibrosis. Lymphatic lacunar cysts are areas of lymphangiectasia. They can be from one to several centimeters in diameter and tend to be more problematic for the mare’s future breeding serviceability. Uterine cysts are diagnosed clinically either during palpation per rectum examination of the uterus (e.g., when they are either large or numerous), during ultrasonography (e.g., when they are smaller or fewer in number) (Figure 17-1), or during hysteroscopy (Figure 17-2). The prevalence of uterine cysts recorded by investigators in one study found at least one cyst in 27% of 295 mares examined by ultrasonography during one breeding season.10 They determined that mares greater than 11 years of age were 4.2 times more likely to have endometrial cysts than mares less than 11. Logistic regression models failed to show a significant impact on the presence of endometrial cysts and successfully establishing and maintaining pregnancy. Adams et al11 reported that single small cysts or even groups of small cysts do not adversely affect fertility. However, mares with greater than five cysts or cysts larger than 1 cm in diameter have lower 40-day pregnancy rates when compared with mares with fewer or smaller cysts. Uterine cysts were associated with a greater embryonic loss rate between means of 22 and 44 days (embryo loss of 24% in mares with cysts versus 6% in mares without cysts), but no effect of fetal loss (44 to 310 days) was found.12 Another report involving 259 mares13 found a slightly lower overall incidence of cysts (22%). However, a significantly lower (P < 0.01) overall day 40 pregnancy rate was found among mares with cysts (71.4%) when compared with mares without cysts (88%). A report from Germany14 documenting endometrial cysts in 11 (13.4%) of 82 mares stated that they found no evidence of cysts in mares less than 10 years of age. Also, mares with endometrial cysts had a 10% higher history of disturbed fertility than mares without endometrial cysts. However, seven of nine mares with cystic structures in the uterus became pregnant.14 Assigning clinical significance to the presence of uterine cysts is therefore a problem in broodmare practice.

Figure 17-1 Ultrasonographic image of a nest of uterine cysts. Markers on the left and top of image equal 1 cm.

It is held that the presence of numerous or large cysts can prevent or obstruct embryonic mobility during prefixation stages and thus jeopardize maternal recognition of pregnancy. Later in pregnancy, nutrient absorption between the yolk sac, or allantois, and endometrial glands may be limited due to intervening contact with large cyst wall(s), thus jeopardizing embryonic or fetal survival. Newcombe15 suggested that when the conceptus begins development adjacent to normal endometrium it is likely to have normal development; however, if it begins development directly adjacent to a cyst, nutrient deprivation may cause pregnancy loss. The observation that larger uterine cysts frequently develop at the junction of the uterine body and horn16 may on occasion lead to problems associated with misdiagnosis of singleton and/or twin pregnancies.

There is a positive correlation between the presence of uterine cysts and degree of endometrial fibrosis observed in histopathologic samples,1–4 as well as with age of the mare.10,13–16 One report, involving the use of videoendoscopic examination of the uterus of subfertile mares, documented that all mares with more than one cyst were classified as category II (Kenney system2), or worse, on their corresponding endometrial biopsies.17 However, the absence of cysts did not exclude the presence of significant histopathologic changes. In the same study, only 4 of the 48 mares that were observed to have had uterine cysts were younger than 10 years of age.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree