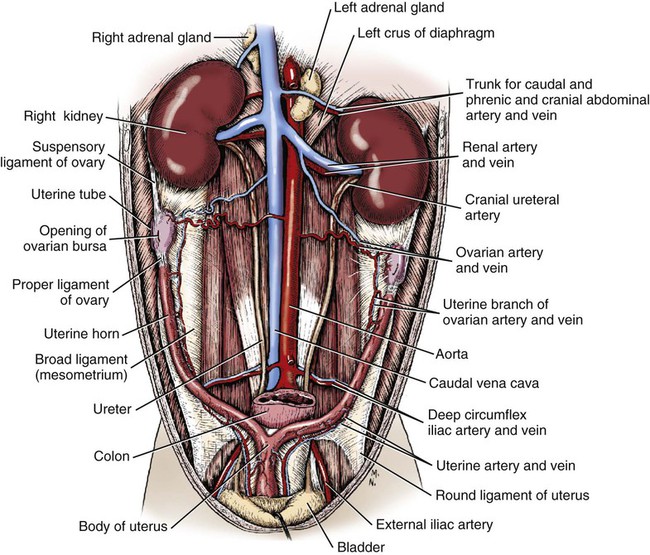

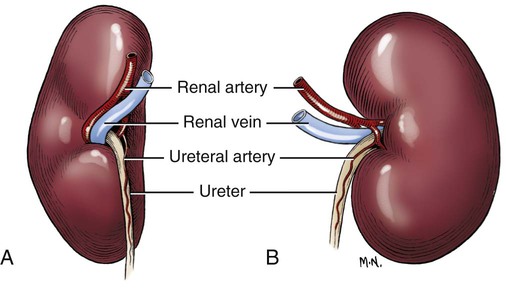

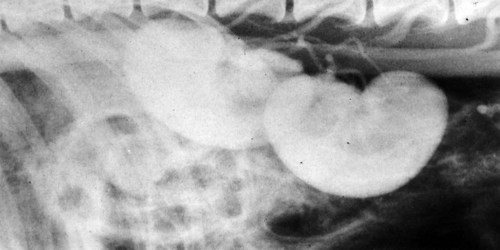

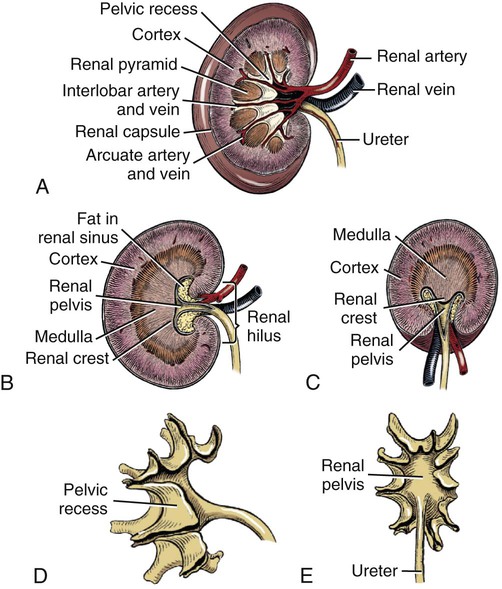

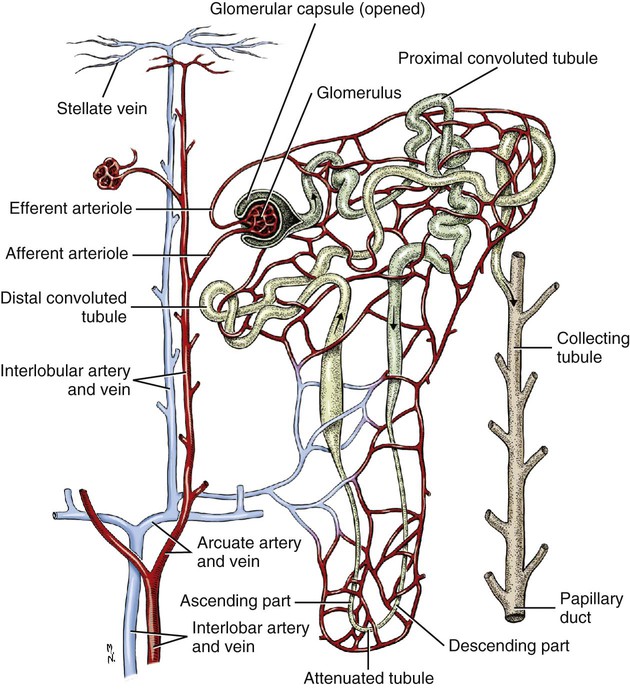

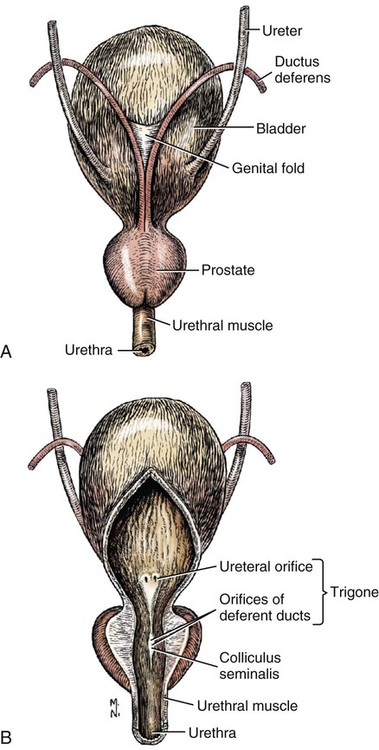

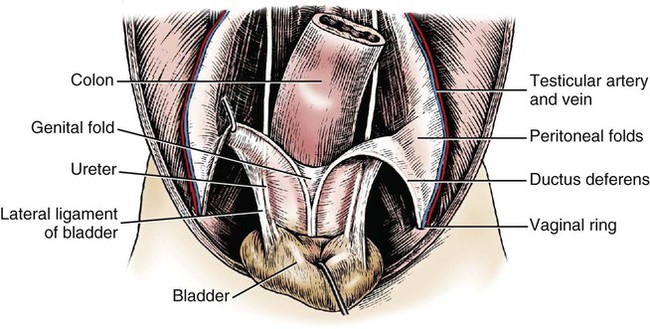

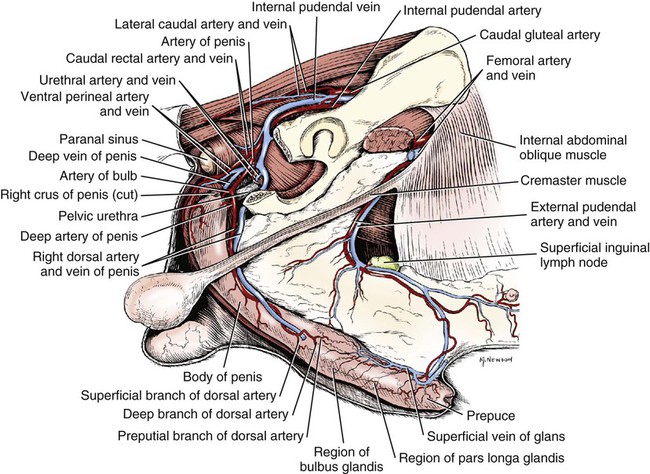

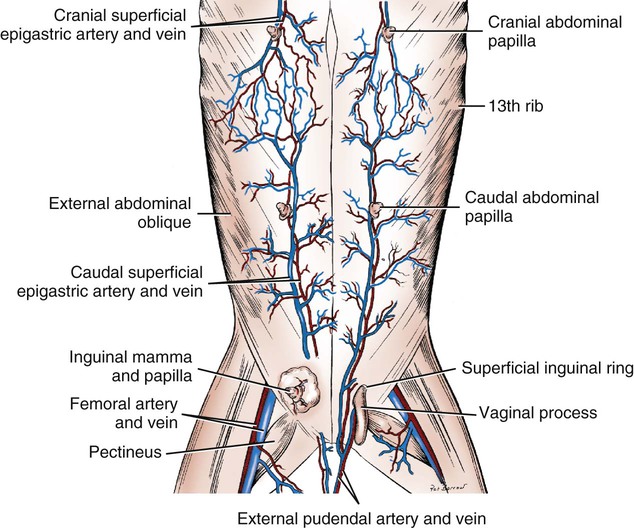

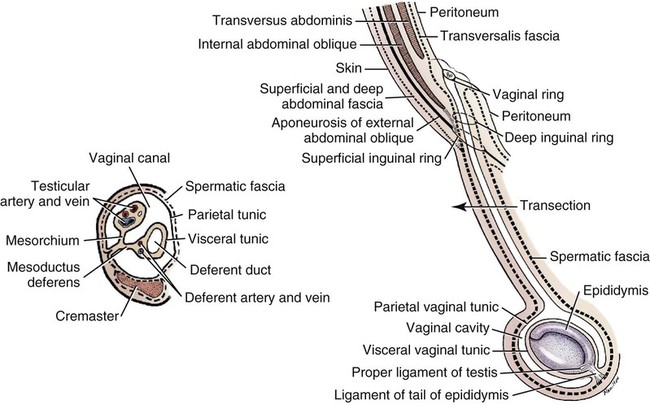

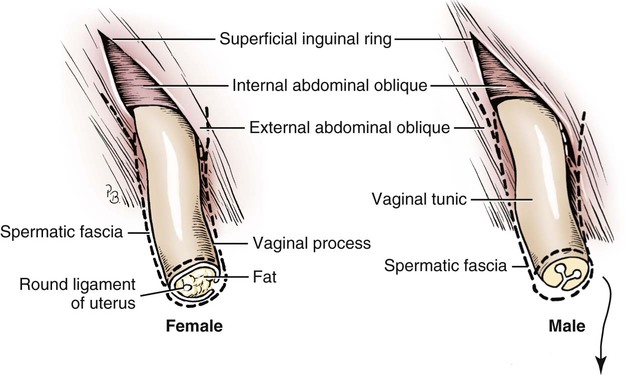

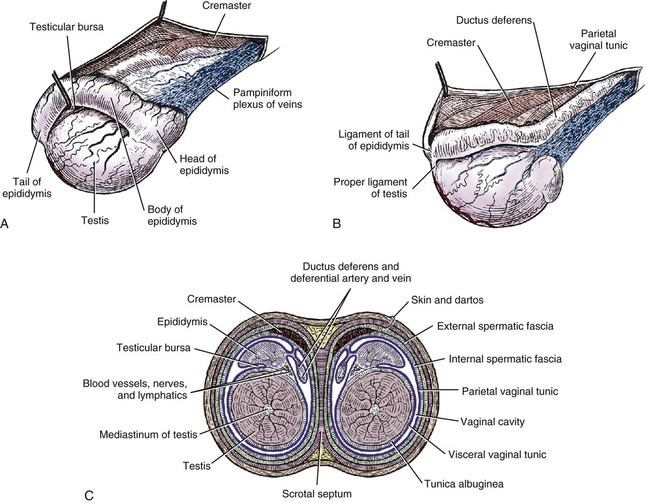

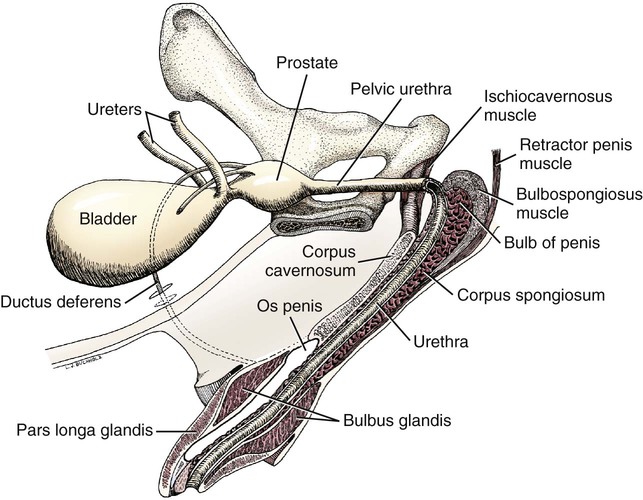

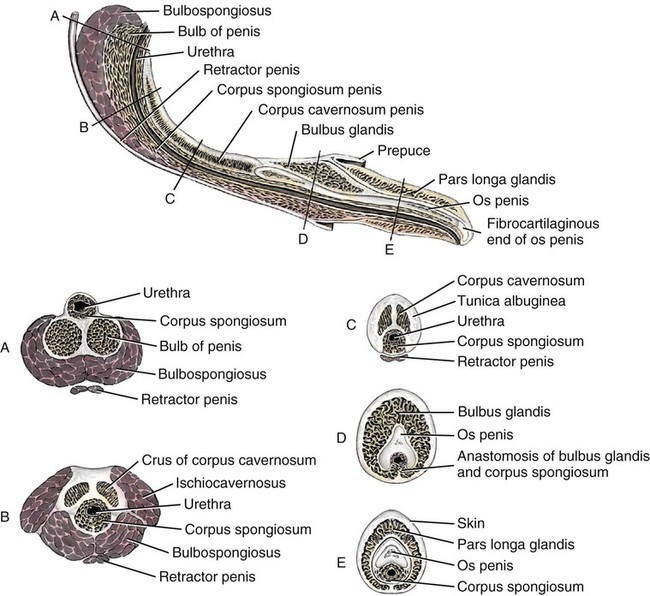

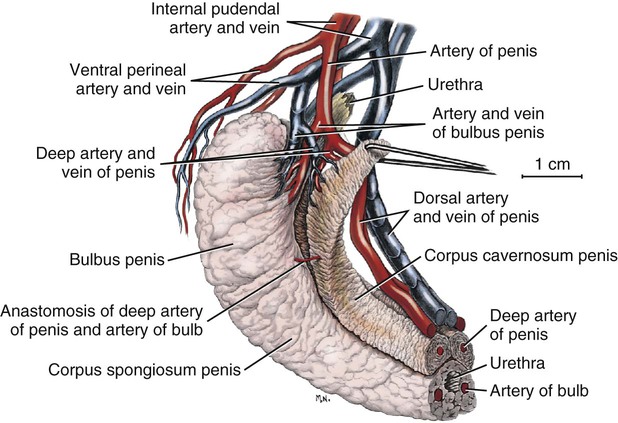

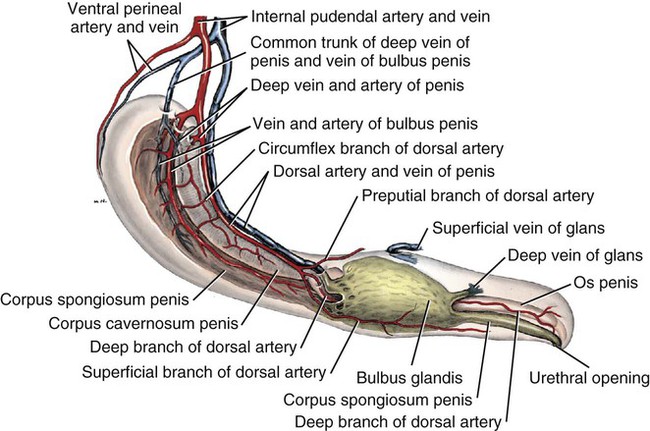

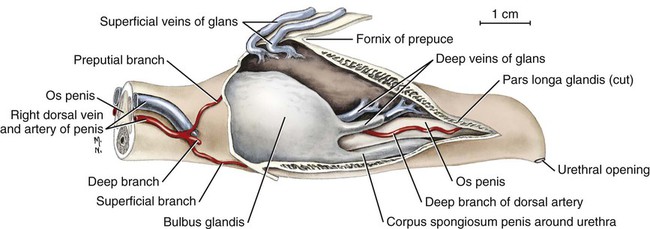

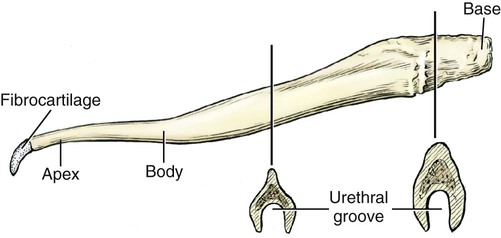

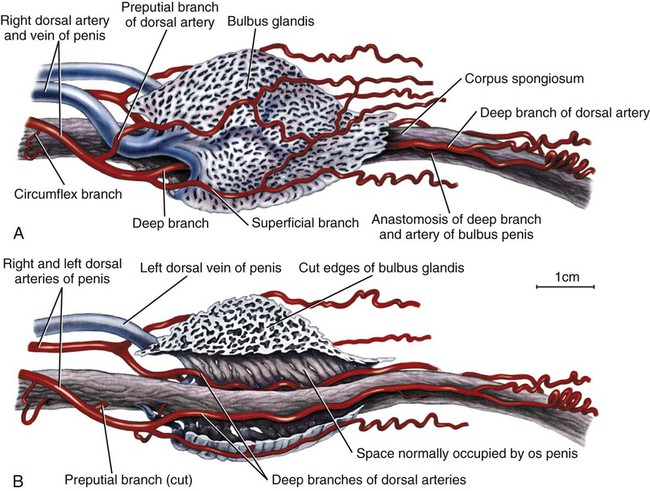

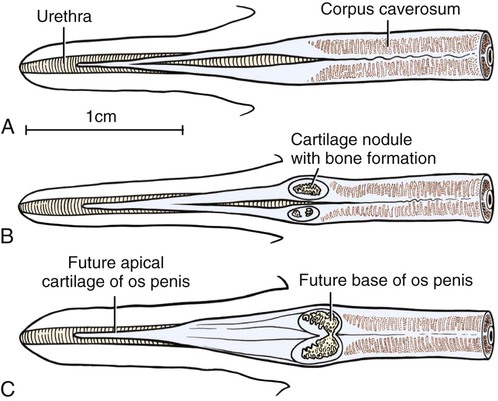

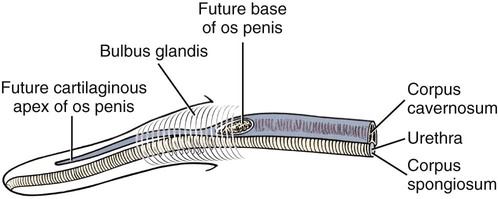

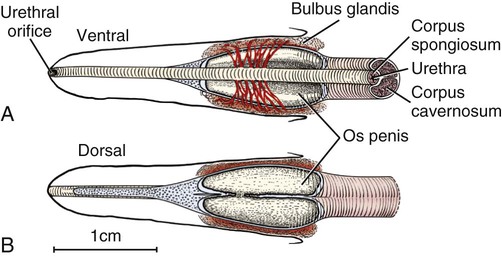

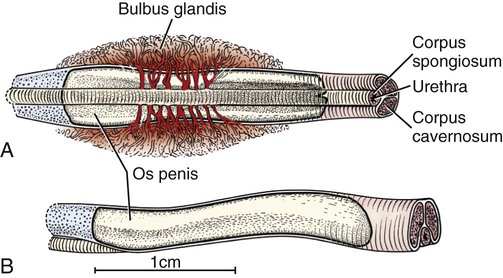

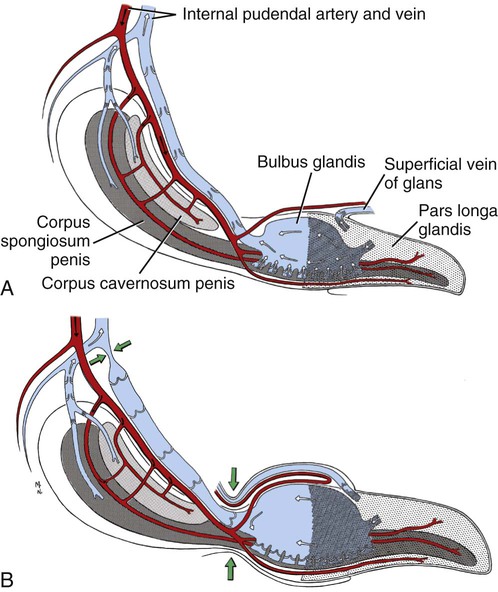

Intersexes and disorders of sexual development in the dog are common (Hare, 1976; Meyers-Wallen & Patterson, 1986). A dog may be a genetic female with a bicornuate uterus and have abdominal testes (Bodner, 1987 in a Doberman; Stewart et al., 1972 in a Pug). For a comprehensive review of intersexes and freemartins and a well-referenced general treatment of the reproductive system in vertebrates see van Tienhoven (1983) and Lamming (1990). A perceptive book by Willis (1962) provides a background for an understanding of pathologic problems resulting from the duality in development of the urogenital system, as does the embryology text by Noden and de Lahunta (1985) and McGeady et al (2009). Pathologic conditions of the reproductive system have been discussed by McEntee (1990), and congenital malformations by Szabo (1989). The kidney (ren), nephros in Greek (Figs. 9-1 to 9-5), is a reddish-brown, paired structure lying against the lumbar hypaxial muscles on either side of the vertebral column. Each kidney has a cranial and a caudal pole, a medial and a lateral border, and a dorsal and a ventral surface. The cranial and caudal extremities are joined by a convex lateral border. The medial border has an indentation, the hilus, that defines a space, the renal sinus. The sinus contains the ureter, renal artery and vein, lymph vessels, and nerves. Of these structures, the renal artery is the most dorsal, and the renal vein the most ventral. Commonly the renal vein is paired on one or both sides, and sometimes the renal artery may also be paired. The nerves and lymphatics lie in close relationship to the renal vein (Bulger et al 1979). The kidneys lie in an oblique position, tilted cranioventrally. The right kidney is more firmly attached to the dorsal wall than is the left and has a correspondingly larger retroperitoneal area. Both kidneys are invested with a fibrous capsule surrounded by adipose tissue and are held in position by transversalis fascia. They are not rigidly fixed and may move during respiration or may be displaced by a full stomach. In some lean animals it is possible to palpate the kidneys, especially the left kidney. The right kidney lies more cranially than the left (see Fig. 9-1) and is in contact with the liver. Grandage (1975) has considered some effects of posture on the radiographic appearance of the kidney. The kidney of an average-sized dog measures 6 to 9 cm in length, 4 to 5 cm in width, and 3 to 4 cm in thickness. The weight of the freshly excised kidney averages 25 to 35 g. Finco et al. (1971) made kidney measurements on radiographs of 27 normal male dogs prior to direct measurement at necropsy to establish a basis for estimating kidney size radiographically. Kidney weight and volume were highly correlated; kidney length was best correlated with kidney weight. Several tables of normal values and variations were presented. The kidney has an indentation or cavity on its medial border referred to as the renal hilus (hilus renalis). The space defined by the walls of the hilus is the renal sinus (sinus renalis) (see Figs. 9-3 and 9-5). The sinus contains the renal pelvis, a variable amount of adipose tissue, and branches of the renal artery, vein, lymphatics, and nerves. After they pass through the sinus, the vessels and nerves enter the parenchyma of the kidney. The renal pelvis (pelvis renalis) (see Fig. 9-5) is a funnel-shaped structure that receives urine from the papillary ducts of the kidney and passes it into the ureter. The pelvis of the kidney is elongated in a craniocaudal direction, and is curved to conform with the lateral border of the kidney. It extends into the renal parenchyma both dorsally and ventrally by means of curved diverticula, the recesses of the renal pelvis (recessus pelvis). There are generally five or six recesses curving peripherally from each border of the pelvis. The parenchyma of the kidney is made up of an internal medulla (medulla renis) and an external cortex (cortex renis) (see Fig. 9-5). When cut transversely (see Fig. 9-5C) the peripheral portion of the renal parenchyma or cortex appears granular, owing to the presence of numerous renal corpuscles and convoluted tubules (nephrons). When the kidney is cut in a dorsal plane, numerous cut ends of arcuate arteries and veins are apparent at the corticomedullary junction. The thickness of the renal cortex is approximately the same as the transverse diameter of the renal medulla. The peripheral surface of the cortex is covered by the fibrous capsule. The nephron (nephronum) (Fig. 9-6) is a continuous contorted tube that serves for urine production and for the regulation of the volume and composition of the extracellular fluid (Reese, 1991). There are approximately 500,000 nephrons in the dog kidney. Each nephron begins at the double-layered glomerular capsule (capsula glomeruli), which is invaginated by a spherical rete of blood capillaries, the glomerulus. Vimtrup (1982) commented on the number, shape, and structure of glomeruli in several mammals. The glomerulus and capsule together form the renal corpuscle (corpusculum renale) (see Fig. 9-6). Renal corpuscles are present in the renal cortex, but not in the medulla. The following components compose the tubular nephron in order from the glomerular capsule to the collecting tubules and papillary ducts in the renal medulla: proximal convoluted tubule, proximal straight tubule, attenuated (thin) tubule that forms a loop, distal straight tubule and distal convoluted tubule. Eisenbrant and Phemister (1979) investigated normal postnatal development of the dog kidney in puppies between 2 and 200 days of age. They found a subcapsular nephrogenic zone was present until approximately 8 days of age. This zone produced new nephrons and interstitial tissues. Deep to the nephrogenic zone there were renal corpuscles of increasing maturity at successively deeper levels. They estimated the total number of nephrons to be 445,000 per kidney and this did not vary significantly during subsequent growth. The corpuscular volume per nephron increased 249% between day 14 and day 200, whereas the increase in the tubular volume per nephron was 303%. Books on renal morphology and function include Smith (1951); The Kidney, in four volumes, by Rouiller and Muller (1969-1971); and The Kidney, in two volumes, by Brenner and Rector (1991). The kidney is a highly vascular organ, as would be expected (Fuller & Heulke, 1973; Morison, 1926). Briefly, blood enters the renal artery from the aorta, goes through end arteries, interlobar vessels, arcuate vessels, interlobular arteries, and finally to glomeruli via afferent arterioles. Efferent arterioles leave the glomeruli and course directly into the outer layer of the medulla, giving rise to long capillary nets that extend to the apical end of the pyramid, or they branch directly into intertubular capillary networks. The intrarenal vascular system of the puppy kidney was described by Evan et al. (1979). The renal artery (arteria renis) bifurcates into dorsal and ventral branches. The site of bifurcation is extremely variable (Christensen, 1952). Variations in the renal artery are common, ranging from a single vessel to one with numerous branches or to completely doubled renal arteries. The two primary branches of the renal artery, end branches, divide into two to four interlobar arteries (aa. interlobares renis). These branch into arcuate arteries at the corticomedullary junction. The arcuate arteries (aa. arcuatae) radiate toward the periphery of the cortex, where they redivide into numerous interlobular arteries (aa. interlobulares). Afferent arterioles (arteriola glomerularis afferens) leave these to supply the glomeruli and thence the efferent arterioles (arteriola glomerularis efferens). The mean glomerular diameter in a 35-pound dog is 170 µm. According to Rytand (1938), there are 408,100 glomeruli in one canine kidney, with a total glomerular volume of 1247 mm3. Finco and Duncan (1972) found a correlation between kidney and nephron size and the body size of the dog. Venous drainage of the kidney stems from the numerous stellate veins (venulae stellatae) in the fibrous capsule. These connect with veins of the adipose capsule and empty into interlobular (vv. interlobulares), arcuate (vv. arcuatae), and interlobar veins (vv. interlobares) before entering the main trunk of the renal vein (vena renis), which joins the caudal vena cava. Venous arcuate vessels, unlike their arterial counterparts, unite to form elaborate arches. Arcuate veins span the medulla to join the dorsal and ventral parts of the kidney. Evan et al. (1979) investigated the vascular system of the puppy kidney between 1 and 21 days after birth. They found the vascular system of the puppy kidney to be strikingly different from that of the adult. The most obvious difference was the lack of peritubular capillaries throughout the cortex. In their place were large sinusoidal vessels directly continuous with the venous system. The vascular arrangement of the efferent arterioles and the sinusoidal vessels appeared to function as a postglomerular shunt. Bentley et al. (1988) examined the architecture and vasculature of the dog kidney using a dynamic spatial reconstructor. This device is a high-speed, volume-scanning, computed, radiotomographic imaging system, which, when used in conjunction with radiopaque methacrylate injections, allowed them to compare casts with the reconstructed images. Interlobar arteries and occasionally arcuate arteries could be clearly detected. Analysis of artery-to-vein transit times showed some to be as short as 3 seconds. Capsular and parenchymal lymphatics are connected to interlobular plexuses that pass into trunks that leave the kidney at the hilus. They terminate in the lumbar lymph nodes. According to Peirce (1944) lymphatics in the kidney accompany the interlobular, arcuate, and interlobar vessels, surrounding them in an irregular network. The periarterial rete is thicker than the perivenous network. Cortical and perirenal lymphatics anastomose (O’Morchoe & Albertine, 1980). Malformations of the kidney are fairly common. Congenital renal cysts and polycystic kidneys occur, although isolated renal cysts are more commonly found. Other congenital anomalies include hypoplasia and aplasia (Hofliger, 1971; Pearson & Gibbs, 1971). Fetal lobation of the kidney may persist in the adult dog. The ureters (Figs. 9-1, 9-2, 9-7, and 9-8) carry urine from the kidneys to the bladder. The diameter of a single ureter measures 0.6 to 0.9 cm when it is distended. The length of the ureter depends on the size of the animal, averaging between 12 and 16 cm in a 35-pound dog. The right ureter is slightly longer than the left because of the more cranial position of the right kidney. The abdominal part of the ureter begins at the renal pelvis, which receives urine from the renal crest. Running caudoventrally and mesially toward the urinary bladder, it is retroperitoneal being bound dorsally by the psoas muscles and ventrally by the peritoneum (see Fig. 9-1). The ureters lie dorsal to the testicular vessels in the male and to the ovarian artery and vein in the female. The right ureter lies in close association with the caudal vena cava and is 1 to 2 cm lateral to the aorta. The ureters pass ventral to the deep circumflex iliac and external iliac arteries and veins. In the male, the ureter crosses dorsal to the ductus deferens, 2 cm from the junction of the ductus deferens with the pelvic urethra. The pelvic part of the ureter enters between the two layers of peritoneum forming the lateral ligament of the bladder and reaches the dorsolateral surface of the bladder just cranial to its neck. In the female, it reaches the lateral ligament of the bladder after being associated with the broad ligament of the uterus. The ureters enter the bladder obliquely and after a short intramural course open by means of two slitlike orifices. Woodburne and Lapides (1972) studied the size and shape of the dog ureter during peristaltic enlargement. They found it to enlarge 17 times during diuresis by thinning of the muscle coats. The collapsed ureter has a stellate lumen with the epithelial surfaces in contact. The urinary bladder (vesica urinaria) (see Fig. 9-7) is a hollow, musculomembranous organ that varies in form, size, and position, depending on the amount of urine it contains. The bladder in a 25-pound dog is capable of holding 100 to 120 mL of urine without being overly distended. When relaxed, the bladder in a 25-pound dog measures 17.5 cm in diameter and 18 cm in length. When contracted, it measures 2 cm in diameter and 3.2 cm in length. The bladder may arbitrarily be divided into a neck (cervix vesicae) connecting with the urethra, a body (corpus vesicae), and a blind cranial part, the apex (apex vesicae). The visceral peritoneum of the ventral surface of the bladder is separated from the parietal peritoneum of the abdominal wall, just cranial to the pubis. The greater omentum frequently occupies the space between these peritoneal layers. The median ligament of the bladder is the peritoneal fold that attaches the ventral surface of the bladder to the linea alba and symphysis pubis. Dorsally, the bladder is in contact with the small intestine (jejunum and frequently ileum) and with the descending colon cranial to the divergence of the uterine horns from the body of the uterus. In the male the deferent ducts and their genital fold lie dorsal to the neck of the bladder, whereas in the female the cervix and body of the uterus are in contact with the dorsal surface of the bladder. When empty, the bladder lies entirely, or almost entirely, within the pelvic cavity. The space on each side of the bladder is occupied by the small intestine. The lateral ligaments of the bladder (lig. vesicae laterales) (Fig. 9-9) connect the lateral surfaces of the bladder to the lateral pelvic walls. They are also triangular in shape. The lateral ligaments of the bladder contain the round ligament of the bladder and the ureter. In the fetus each lateral ligament contains a large umbilical artery that extends cranially along the rudimentary bladder and courses in the median ligament of the bladder with the urachus to the umbilicus. The urachus is the stalk of the allantois, which connects from the apex of the rudimentary bladder to the allantoic portion of the fetal membranes. Before birth, the bilateral umbilical arteries (branches of the internal iliac arteries) carry blood from the fetus to the placenta and are components of the umbilical cord. When the umbilical cord is severed at birth, the arteries retract and become fibrous cords between the bladder and the umbilicus that disappear in the young dog and are rarely visible in adult dogs. The narrowed lumen of each umbilical artery remains patent between the internal iliac artery and the bladder, where the relatively minute cranial vesical artery leaves the umbilical artery to vascularize the apex and body of the bladder. The remnants of these arteries in the lateral ligaments of the bladder are referred to as the round ligaments of the bladder (lig. teres vesicae). The ureter and round ligament of the bladder cross at nearly right angles to each other at the junction of the broad and lateral ligaments. The ureter is the more mesial of the two structures. The lateral ligaments of the bladder, in the female, blend laterally with the broad ligament of the uterus (mesometrium) as well as with the lateral pelvic wall. In the male, the ureter and ductus deferens cross each other a few centimeters from the entrance of the ureters into the bladder (see Fig. 9-7). The ductus deferens is suspended by the mesoductus deferens, a fold of peritoneum, which at the vaginal ring separates from the mesorchium, which is the peritoneal fold containing the testicular vessels and nerves. The ductus deferens and its mesoductus deferens course dorsocaudally, dorsal to the ureters in the lateral ligaments of the bladder to terminate in the prostatic urethra. Dorsal to the bladder a short fold of peritoneum connects between each ductus deferens. This is the genital fold (plica genitalis). In the female this genital fold connects between the two uterine horns. The peritoneal pocket between the rectum and the genital fold and the two ductus deferens or the initial part of the two uterine horns, the uterus and cranial vagina is the rectogenital pouch (excavatio rectogenitalis). A small pubovesical pouch (excavatio pubovesicalis) is present between the bladder and its lateral ligaments and the pubis The urinary bladder receives its major blood supply through the caudal vesical arteries. These are branches of the vaginal or prostatic arteries that are branches of the internal pudendals from the internal iliac arteries. The small cranial vesical artery from the umbilical supplies the bladder apex. The venous plexus on the urinary bladder drains primarily into the internal pudendal veins. The lymphatics of the bladder drain into the hypogastric and lumbar lymph nodes (Baum, 1918). Petras and Cummings (1978) describe the location of the cells of origin for the sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation of the urinary bladder and urethra in the dog. Their study, using horseradish peroxidase injected into the bladder and urethra and counterstained with cresyl violet, demonstrates the presence of both sympathetic and parasympathetic intramural ganglia and axons. Thus there is a direct preganglionic sympathetic pathway to the urinary bladder and urethra in addition to the postganglionic sympathetic innervation. The reproductive system in vertebrates is a most varied assemblage of primary and accessory organs and parts, which begin developmentally in a similar fashion but result in strikingly different forms in the adult. In recent years the study of reproduction in animals (theriogenology) has made great strides, and as a result of our new understanding we are now able to manipulate the system in many ways such as to facilitate artificial insemination, egg or embryo transfer, freezing and storage of eggs and embryos and cloning of various species. For explanations of developmental processes in domestic animals see Noden and de Lahunta (1985). For an overall view of the reproductive system from fish to humans there is nothing better than Marshall’s Physiology of Reproduction. The most recent revision of Marshall’s by Lamming (1990-1992) devotes one volume to a consideration of reproductive cycles and female anatomy, a second to reproductive structures and functions of the male, and a third to pregnancy and lactation. Other books on the reproductive system include Austin and Short (1982), Segal et al. (1973), and Cupps (1991). For information on the reproductive habits, cycles, and gestations of mammals of the world, including canids, reference should be made to Asdell’s Patterns of Mammalian Reproduction: A Compendium of Species-Specific Data by Hayssen and van Tienhoven (1993). The canine male genital organs (organa genitalia masculina) (Figs. 9-10 to 9-34) consist of the scrotum, the testes, the epididymides, the deferent ducts, the spermatic cord, the prostate gland, the penis, and the urethra. The scrotum (see Figs. 9-14 and 9-15) is a pouch of skin divided by a median septum into two components, each of which is occupied by a testis, an epididymis, and the distal part of the spermatic cord. The scrotal septum (septum scroti) is a median partition that is made up of all the layers of the scrotum except the skin. In the dog, the scrotum is located approximately two thirds of the distance from the preputial opening to the anus. It lies between the thighs and has a spherical shape, indented in an oblique craniocaudal direction by an indistinct raphe scroti. The left testis is usually farther caudad than the right, allowing the surfaces of the testes to glide on each other more easily and with less pressure. Extending into each scrotal sac is an evaginated pouch of peritoneum, the vaginal tunic (tunica vaginalis) (see Figs. 9-12 and 9-14), covered by spermatic fascia of the abdominal wall. The vaginal tunic and fascia wrap the descended testis and spermatic cord in such a way as to result in a double-walled extension of abdominal peritoneum. This was a vaginal process before the descent of the testis with its duct system, vessels, and nerves (see Figs. 9-12 and 9-15) Zietzsehman (1928). The outer wall, or parietal layer of the vaginal tunic, is separated by a space, the vaginal canal (canalis vaginalis) or vaginal cavity (cavum vaginale), from the visceral layer of the vaginal tunic. The vaginal canal surrounds the spermatic cord and the vaginal cavity surrounds the testis. The vaginal canal is continuous with the peritoneal cavity at the vaginal ring. The development of the vaginal tunic in the male and the vaginal process in the female is similar. As the evaginating peritoneum passes through the deep inguinal ring, it is invested by the transversalis fascia; as it emerges from the superficial inguinal ring it is joined by the superficial and deep abdominal fascia. The combined fascias form the spermatic fascia, which covers the parietal layer of the vaginal tunic (see Fig. 9-12 ). The cremaster muscle (see Fig. 9-14) arises from the caudal free border of the internal abdominal oblique (or occasionally from the transversus abdominis) and inserts on the spermatic fascia and parietal layer of the vaginal tunic. The action of the muscle is protective in that it reflexly pulls the testis closer to the body in response to cold. The scrotum, because of its thin, hairless skin, its lack of subcutaneous fat, and its ability to contract toward the body, functions as a temperature regulator for the tail of the epididymis. Evidence indicates that the epididymis, as the site of sperm storage, is the most heat-sensitive region of the male reproductive tract (Bedford, 1978). When the question is raised as to why a scrotum exists in some animals and not in others (there are approximately 1500 ascrotal species) we still do not have a satisfactory answer. Freeman (1990) has reviewed the question and came to the conclusion that the scrotum evolved to provide a cool environment for sperm storage, and testicular descent evolved because it improves sperm quality so that fewer are needed. He provides tables that show the proportional size of the testes in many species of animals. There are six mammalian orders that have species with internal testes as well as species with external testes. The genital rami, branches of the genitofemoral nerve from the ventral branches of the third and fourth lumbar nerves, innervate the skin of the prepuce. The superficial perineal nerve, a branch of the pudendal from sacral nerves 1, 2, and 3, supplies all of the scrotum, according to Spurgeon and Kitchell (1982b). Postganglionic sympathetic axons supplying the tunica dartos enter via the sacral plexus and the pudendal and superficial perineal nerves. The testis, or male gonad (see Fig. 9-14), is oval in shape and located within the scrotum. The length of the testis in a 25-pound dog averages 3 cm and the width 2 cm. The fresh organ weighs approximately 8 g. In normal position, the testis of the dog is situated obliquely, with the long axis running dorsocaudally. The epididymis is adherent to the dorsolateral surface of the organ, with its head located at the cranial end and its tail at the caudal extremity of the testis. The surface of the testis is invested by the tunica albuginea, a dense, white fibrous capsule. Covering the testis most immediately is the visceral vaginal tunic, a serous membrane continuous with the peritoneum of the spermatic cord and the abdominal cavity. The tunica albuginea joins the centrally located mediastinum testis by means of interlobular connective tissue lamellae (septula testis), which converge centrally. The mediastinum testis is a cord of connective tissue running lengthwise through the middle of the testis. The lobuli testes (wedge-shaped portions of testicular parenchyma) are bounded by the septula. The lobuli contain the convoluted seminiferous tubules (tubuli seminiferi contorti), a large collection of twisted canals. Spermatozoa are formed within the epithelial lining of the tubules, which contains spermatogenic cells and sustentacular (Sertoli) cells. The organization, motility, and structure of sperm cells have been reviewed by André (1982). The longevity of spermatozoa in the reproductive tract of the bitch can be several days (Doak et al., 1967), and at least 6 days as shown by Concannon, Whaley, and Lein (1983). HE Straight seminiferous tubules (tubuli seminiferi recti) are formed by the union of the convoluted seminiferous tubules of a lobule. The mediastinum testis contains a network of confluent spaces and ducts called the rete testis. These connect the straight tubules with the efferent ductules (ductuli efferentes testis). Testicular blood vessels and lymphatics enter and leave through the mediastinum. The lobuli testis also contains interstitial cells (of Leydig) between tubular elements. Johnson et al. (1970) and Setchell (1978) consider the anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, and other parameters of the testis. The testicular artery and the artery of the ductus deferens supply the testis and epididymis. The testicular artery (homologue of the ovarian artery of the female) arises from the ventral surface of the aorta at the level of a transverse plane through the fourth lumbar vertebra. The right artery originates cranial to the left, corresponding to the embryonic positions of the testes. The artery of the ductus deferens, a branch of the prostatic artery from the internal pudendal, follows the ductus deferens into the spermatic cord to the level of the epididymis. It sends branches to the epididymis and anastomoses with the testicular artery. The testicular vein follows the arterial pattern but forms an extensive pampiniform plexus (plexus pampiniformis) in the spermatic cord, surrounding the testicular artery lymphatics, and nerves. The right testicular vein empties into the caudal vena cava at the level of the origin of its arterial counterpart. The left drains into the left renal vein. Harrison (1949) made a detailed comparative study of the vascularization of the mammalian testis. The testicular and epididymal lymphatics anastomose into a variable number of trunks that drain into the lumbar lymph nodes (see Chapter 13). The nerve supply to the testis is derived from the sympathetic division of the general visceral efferent component of the autonomic nervous system. The nerves of the testicular plexus accompany the testicular arteries distally and enter the testis with either the blood vessels or the efferent ducts. Indirectly, they are derived from the fourth, fifth, and sixth lumbar sympathetic trunk ganglia. The testicular plexus is derived from the abdominal aortic plexus at the level of the origin of the testicular arteries. These testicular vessels, lymphatics and nerves are suspended in the spermatic cord by the mesorchium, which is a fold of the visceral layer of the vaginal tunic. This is continued in the abdomen as a fold of the parietal layer of the peritoneum. The blood vessels and smooth muscle fibers in the testis receive a sympathetic nerve supply, but the seminal epithelium and the interstitial secretory tissue do not. Elimination of the sympathetic nerve supply to the testis is followed by degeneration of the seminal epithelium and hypertrophy of the interstitial secretory tissue (Kuntz, 1919b). The degenerative changes are considered to be the result of paralysis of the blood vessels in the spermatic cord and testis. Cryptorchidism, or failure of the testis to descend, is the most important congenital anomaly of the testis. This condition is comparatively frequent and is believed to be hereditary in some instances. Cox et al. (1978) investigated 12 cases of cryptorchidism in Miniature Schnauzers. Five were unilateral and seven were bilateral. All of the unilateral cases had retained testes on the right side. When retained testes were bilateral the right testis was always smaller. Their observations suggested a multigene defect. In a cryptorchid animal one or both testes are retained either in the abdominal cavity (in the region of the inguinal canal) or between the superficial inguinal ring and the scrotum. Sterile, cryptorchid dogs usually possess normal sexual desire. For a discussion of cryptorchidism see Wensing and van Straten (1980). Hayes et al. (1985) studied 1.8 million documented medical records and identified 2912 dogs (in 104 different breeds) that had cryptorchid testes. There were 14 breeds with significantly high risk. According to Runnells (1954) testicular tumors of dogs have been reported to cause anatomic alterations, such as atrophy of the opposite testis and enlargement of the prepuce and prostate gland. Hayes et al. (1985) reported that testicular tumors were found in 5.7% of the 2912 cryptorchid dogs whose records they reviewed. Half had Sertoli cell tumors, and one-third had seminomas. Male pseudohermaphroditism and true hermaphroditism have been reported in the dog by Lee and Allam (1952), Brodey et al. (1954), and Bodner (1987). Female pseudohermaphroditism, considered rare (Meyers-Wallen & Patterson, 1986), was reported by Olson et al. (1989) in three sibling Greyhounds. In the majority of mammalian species the testes migrate from their developmental position within the abdomen near the kidneys to a location outside of the body wall, usually in a scrotum (see Fig. 9-15). For these species, including the dog, if neither testis descends (bilateral cryptorchid) spermatogenesis is eliminated and the animal is infertile. If only one testis descends (monorchid or unilateral cryptorchid) fertility is lessened. (Many rodents have testes that descend periodically coincident with breeding. In such species the testes can be gently squeezed back into the body cavity at any time because of the large inguinal canal.) Much important research on testicular descent in domestic animals has been conducted at the Institute of Veterinary Anatomy of the State University at Utrecht, the Netherlands, by Wensing and co-workers: Wensing (1968, 1973a, 1973b, 1980); Baumans et al. (1981, 1982, 1983); Baumans (1982); Wensing and Colenbrander (1986). Whereas in most mammals testicular descent occurs in fetal life, in the dog it occurs at approximately the time of birth and this makes the dog a good subject for the study of the mechanics and hormonal control of descent. A descriptive and illustrated experimental study of normal development and the factors responsible for the descent of the testes in the dog was published as a thesis in the Netherlands by Baumans (1982). (Included in the thesis are six papers with co-workers, each with a bibliography.) Baumans found that the major factors essential for the descent were first an outgrowth and then a regression of the gubernaculum testis. The gubernaculum is a mesenchymal mass enclosed in a fold of peritoneum that extends from the testis across the mesonephros (kidney ridge) to the inguinal area. It is attached to the caudal pole of the testis and epididymal part of the mesonephric duct. Its distal end continues through the abdominal wall where the inguinal canal forms around it. Here, the gubernaculum is invaded by an outgrowth of parietal peritoneum, the vaginal process. During fetal growth the testis moves caudally to the level of the inguinal canal as the trunk elongates. There are two phases of the migration of the testis through the inguinal canal and into the scrotum. In the first phase the extra-abdominal part of the gubernaculum increases enormously in length and volume expanding beyond the inguinal canal and dilating it. When this expansion exceeds the size of the testis and passive resistance is reduced, the testis passes through the canal adjacent to the vaginal process. Here it rests in a mass of swollen gubernaculum, which is still covered by vaginal process peritoneum. An important feature of this testicular migration is that the testis brings with it the visceral peritoneum that formed around it at its site of development in the dorsal abdominal wall. Completion of this first phase of testicular descent initiates the second phase in which the gubernaculum is transformed by tissue degeneration from an expanded mucoid mass into a small fibrous structure in the scrotal sac, thus making room for the testis. This converts the gubernaculum into the proper ligament of the testis, which attaches the tail of the epididymis to the testis, and the ligament of the tail of the epididymis, which attaches the tail to the distal portion of the vaginal tunic and spermatic fascia. The latter is derived from the remnants of the gubernaculum that surrounds the vaginal tunic. The degeneration of the gubernaculum results in the testis being located at the distal extent of the vaginal tunic. To test the factors responsible for gubernacular growth and regression, Baumans removed the testes in fetal dogs and found that gubernacular outgrowth ceased and there was no epididymal descent. Removal of the testis at birth resulted in retarded gubernacular regression and a delayed epididymal descent. After further investigation it was concluded that the testis induces gubernacular outgrowth and regression and thereby regulates its own descent. It was found that testicular hormones, particularly testosterone, are synthesized in the testis. In the first phase of descent an unidentified testicular factor stimulated gubernacular proliferation and swelling. Sustentacular cells are thought to be the source of this factor. In the second phase of descent testosterone induced gubernacular regression. In regard to the mechanical role of the gubernaculum, it was found that a connection between the testis and the gubernaculum (see Fig. 9-15) was essential for normal testicular descent. By the end of the second phase of descent the testis plays a mechanical role in distending the scrotum. Wensing and Colenbrander (1986), in discussing normal and abnormal descent of the testis, make a distinction between the morphologic characteristics of testicular descent in mammals with a striplike cremaster muscle (ungulates, dog, and humans) and those with a saclike cremaster muscle (rodent, lagomorph). They believe that the bilaminar saclike cremaster muscle of rodents and lagomorphs continues to grow and increase in size even after the regression of the gubernaculum and thus plays a role in descent of the testis. Regardless of the morphologic characteristics of the cremaster muscle, they stress the importance of a normal gubernacular outgrowth and regression for affecting testicular descent. Their experimental results showed that the first phase in the descent process (gubernacular outgrowth) does not depend on the presence of active interstitial cells, testosterone, testosterone receptors, or gonadotropins, although the presence of the testis is essential. The epididymis (see Fig. 9-14) is where spermatozoa are stored before ejaculation. It is comparatively large in the dog and consists of an elongated convoluted tube, the coils of which are held together by collagenous connective tissue. The epididymis lies along the dorsolateral border of the testis. The head (caput) begins on the cranial medial surface of the testis but immediately twists around the cranial extremity to attain the lateral side. It is slightly larger than the remainder of the epididymis. It continues as the body (corpus), which runs along the dorsolateral surface of the testis, and then as the tail (cauda epididymidis), which is attached to the caudal extremity of the testis by the proper ligament of the testis. Beyond the tail this duct is continued craniodorsally as the ductus deferens which becomes part of the spermatic cord along with the testicular vessels and nerves. The epididymis has its concave surface in juxtaposition with the testis. Its medial edge is attached to the testis by visceral vaginal tunic, the distal mesorchium (mesorchium distale). The latter extends medially between the lateral edge of the body of the epididymis and the testis, forming a potential space, the testicular bursa (bursa testicularis). The bursa is limited cranially and caudally by the epididymal head and tail, which adhere tightly to the testis. The epididymis, especially the caudal portion, has a lower temperature than the rest of the body because of its position in the scrotum and is a favorable storage place for spermatozoa before their passage into the ductus deferens (Bedford, 1978). Circular smooth muscle fibers aid seminiferous tubule secretion in moving the germ cells. The length of the epididymis and the slowness of spermatozoa movement are important in allowing the spermatozoa to complete their maturation process, called capacitation (Mason & Shaver, 1952). The deferent duct (ductus deferens) (see Figs. 9-16 to 9-18) is the continuation of the duct of the epididymis. Beginning at the tail of the epididymis, it passes cranially along the dorsomedial border of the testis, continues dorsally in the spermatic cord, and enters the abdominal cavity through the inguinal canal. Running in a fold of peritoneum, the mesoductus deferens, it crosses ventral to the ureter at the lateral ligament of the bladder and penetrates the prostate to open into the pelvic urethra, lateral to the colliculus seminalis. In a 25-pound dog, the ductus deferens averages 17 to 18 cm in length and 1.6 to 3 mm in diameter. The epididymal end of the duct is slightly tortuous, but it straightens out in its course along the medial surface of the testis. It is attached to the testis, along with the artery and vein of the ductus deferens, by a special fold of the visceral vaginal tunic called the mesoductus deferens. At the cranial extremity of the testis the mesoductus deferens blends with the peritoneal fold containing the testicular vessels, nerves, and lymphatics, the proximal mesorchium (mesorchium proximale) (see Fig. 9-12). In the abdominal cavity at the vaginal ring the deferential fold of peritoneum leaves the vaginal ring, to which it is attached at one edge, and courses caudodorsally to reach the dorsal surface of the bladder. The ductus deferens lies 3.4 cm from the body wall when the deferential fold of peritoneum is stretched out. Dorsal to the bladder, the right and left deferent ducts come into close apposition approximately 2 cm before they penetrate the prostate gland. For approximately 1.5 cm before they contact each other, the ducts are joined by a fold of peritoneum, the genital fold (plica genitalis). Peritoneum covering the pelvic portion of the ductus is reflected ventrally onto the prostate, bladder, and ureters. Dorsally, it is reflected over the prostate and then onto the ventral surface of the rectum at the rectogenital fossa. Each spermatic cord (funiculus spermaticus) (see Figs. 9-12 and 9-16) is composed of the ductus deferens and its vessels, and the testicular vessels and nerves, along with their serous membrane coverings, the mesoductus deferens and the mesorchium. These structures pass through the inguinal canal during the descent of the testis. The spermatic cord begins at the vaginal ring, the point at which its component parts converge to leave the abdominal cavity via the inguinal canal. The ductus deferens, which arises from the tail of the epididymis, leaves the vaginal ring, runs caudomedially in the deferential fold of peritoneum, and enters the prostate gland before opening into the prostatic part of the pelvic urethra. The ductus deferens is accompanied by the small artery of the ductus deferens, which arises from the prostatic artery and the vein of the ductus deferens, which drains into the internal iliac vein. The testicular artery originates from the ventral surface of the aorta. The testicular arteries arise cranial to the origin of the caudal mesenteric artery. The testicular artery runs laterally and caudally, crossing the ventral surface of the ureter, at which point it is joined by the testicular vein and nerve. The left testicular vein empties into the left renal vein and the right into the caudal vena cava. The peritoneal fold, the proximal mesorchium, enclosing the testicular vessels is attached to the abdominal wall in a line slightly lateral to the junction of the transversus abdominis and psoas muscles. The plexus of the testicular nerves arises from the area of the sympathetic trunk between the third and the sixth lumbar sympathetic trunk ganglia. The testicular lymph vessels pass to the lumbar lymph nodes. The components of the spermatic cord are joined together by loose connective tissue and are surrounded by the visceral layer of the vaginal tunic. The peritoneal ring formed by the vaginal tunic passing through the deep inguinal ring is termed the vaginal ring (see Fig. 9-12). There is usually an irregular mass of fat at the vaginal ring, covered by peritoneum. It overlaps the cranial border of the ring and probably acts as a valve to decrease the possibility of intestinal or omental herniation. The fat mass may be in two separate parts. The inguinal canal (see Fig. 9-12) is a fissure through the abdominal muscles that connects the deep and the superficial inguinal ring (Ashdown, 1963; McCarthy, 1976). It is located approximately 1 cm craniomedial to the femoral ring. The femoral ring affords passage for the femoral vessels. The inguinal canal is bounded medially by the rectus abdominis muscle, cranially by the internal oblique muscle, and both laterally and caudally by the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique muscle. The superficial ring, located 2 to 4 cm lateral to the linea alba, is merely a slit in the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique muscle. It represents where the abdominal wall formed around the gubernaculum in the fetus. The cranial wall of the inguinal canal is made up of the transversus abdominis and internal abdominal oblique muscles, as well as the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique muscle. Only the latter forms the caudal wall of the canal. Both scrotal and inguinal hernias may occur in male dogs. In both of these hernias abdominal organs (greater omentum or a loop of jejunum) enter the canal of the vaginal tunic. Inguinal hernias remain in the inguinal canal. The hernia may be bilateral or unilateral. For a description of surface palpation of the superficial inguinal ring, see McCarthy (1976). Inguinal hernia (intestines or omentum pushing into the inguinal canal within the vaginal canal) is recognizable as a soft, fluctuating enlargement to one side of the penis. The prostate gland (prostata) (see Figs. 9-7, 9-16, 9-18 and 9-20) completely envelops the proximal portion of the male pelvic urethra at the neck of the bladder. It is the only accessory sex gland present in the male dog. The prostate develops from a series of symmetric buds of the pelvic urethra that appear at approximately the sixth week of gestation (Price, 1963). The size and weight of the prostate varies, depending on the age, breed, and body weight of the dog (Berg, 1958a; O’Shea, 1962). In most dogs, progressive enlargement occurs with age (Schlotthauer & Bollman, 1936). The latter authors found that in all dogs in which there was more than 0.7 g of prostate per kg of body weight, the prostate was abnormal on histologic examination. They suggested 0.7 g prostate per kg of body weight as the upper limit of normality for the dog. O’Shea (1962) divided prostatic growth into three phases: normal growth in the young adult, hyperplasia during the middle of adult life, and senile involution. The prostate is bounded dorsally by the rectum and ventrally by the symphysis pubis and ventral abdominal wall. Its craniocaudal position is age-dependent, as discussed by Gordon (1961). The prostate lies entirely within the abdominal cavity until the urachal remnant breaks down at approximately 2 months of age. From that time until sexual maturity the gland is confined to the pelvic cavity. With sexual maturity it increases in size and extends cranially. By 4 years of age more than half of the gland is abdominal, and by 10 years of age the entire gland is in the abdomen. The degree of bladder distention was not found to alter these relationships to any significant degree. The prostate is androgen-dependent, and castration at any age results in a marked reduction in size (Hansel & McEntee, 1977). The dorsal surface of the prostate is separated from the ventral surface of the genital fold and the two ductus deferentia by the two layers of the fold of peritoneum that bounds the vesicogenital space. The ventral surface of the prostate is retroperitoneal; the ventral sheet of the lateral ligament of the bladder is not continued onto the prostate. A layer of fat usually covers the ventral surface. In mature dogs, the caudal third of the dorsal surface of the prostate is attached to the rectum by a fibrous band (Gordon, 1960). The two deferent ducts enter the craniodorsal surface of the prostate. They lie adjacent to each other, one on either side of the median plane. They run caudoventrally through the dorsal part of the gland to open into the urethra by two slits on each side of the seminal colliculus (colliculus seminalis) (see Fig. 9-7). The latter is a small round eminence in the center of the urethral crest (crista urethralis), which is a short longitudinal fold on the dorsal wall of the prostatic part of the pelvic urethra. The distal portion of the ductus deferens that enters the urethra is referred to as the ampulla (ampulla ductus deferentis) because of its enlargement resulting from the presence of mucosal glands. In the dog this ampulla is very small and difficult to recognize. The function of the prostate is not entirely understood. Prostatic secretion contains citrate, lactate, cholesterol, and a number of enzymes. It is believed to be essential to provide an optimum environment for sperm survival and motility. Dog semen is unique in its absence of reducing sugars supplied by the accessory glands in other species; the source of readily metabolizable energy for the spermatozoa is unknown (Hansel & McEntee, 1977). The blood and nerve supply of the prostate have been studied by Gordon (1960) and Hodson (1968). The prostatic artery (a. prostatica) arises from the internal pudendal at the level of the second or third sacral vertebrae, although it may arise from the umbilical (Hodson, 1968) near its origin. The prostatic artery gives rise to the artery of the ductus deferens (a. ductus deferentis), which is homologous with the uterine artery in the female. The artery of the ductus deferens gives rise to the caudal vesicle artery (a. vesicalis caudalis). The caudal vesicle artery gives branches to the ureter (ramus uretericus) and urethra (ramus urethralis) and then ramifies on the surface of the bladder, anastomosing with the contralateral caudal vesicle and cranial vesicle arteries. When the cranial vesicle artery is not present, the caudal vesicle supplies the entire bladder. The prostatic artery continues caudoventrally and gives rise to the small middle rectal artery (a. rectalis media) before ramifying on the surface of the prostate. These branches penetrate the capsule on the dorsolateral surface of the gland to become subcapsular arteries (Hodson, 1968). Radial tributaries pass along the capsular septae toward the urethra to supply the glandular tissue. Cavernous tissue, continuous with the corpus spongiosum, surrounds the pelvic urethra. It is supplied by the artery of the bulb of the penis. Anastomoses occur between the prostatic vessels and the urethral artery (internal pudendal), the cranial rectal artery (caudal mesenteric) and the caudal rectal artery (internal pudendal). These anastomoses complicate prostatectomy. The venous network of the gland drains by way of the prostatic and urethral veins into the internal iliac vein. The prostatic lymph vessels empty into the iliac lymph nodes. The nerve supply to the prostate is closely allied to the vasculature. The hypogastric nerve, which supplies sympathetic innervation to the prostate, follows the prostatic artery from the pelvic plexus. The pelvic nerve, which may be single or double (Gordon, 1960), accompanies the prostatic artery as far as the lateral surface of the rectum. Here it forms the pelvic plexus, together with branches of the hypogastric nerve. The middle portion of the pelvic plexus forms the prostatic plexus, which innervates the gland. Parasympathetic stimulation increases the rate of glandular secretion.

The Urogenital System

Urinary Organs

Kidneys

Position and Relations

Structure

The Nephron

Vessels and Nerves

Anomalies

Ureters

Urinary Bladder

Fixation

Vessels and Nerves

Reproductive Organs

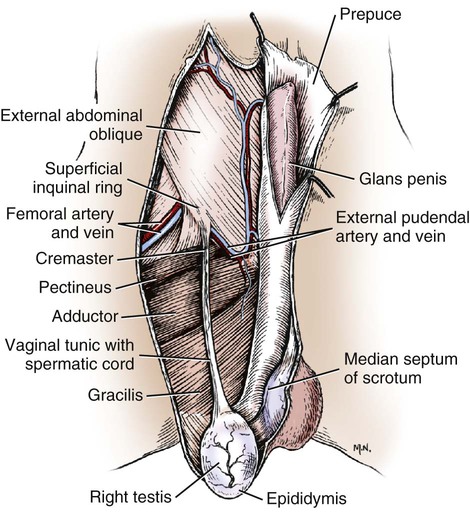

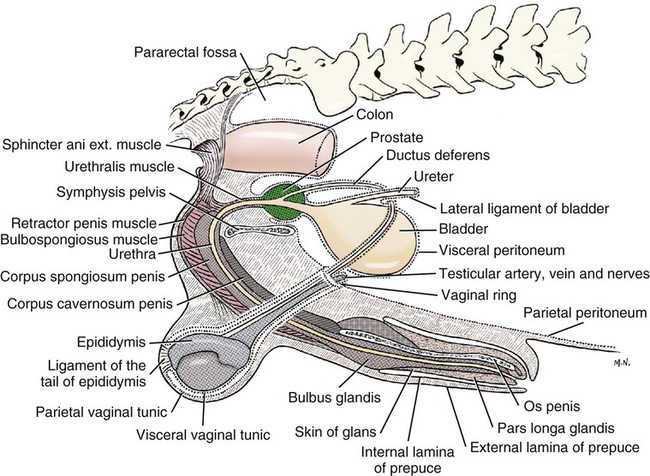

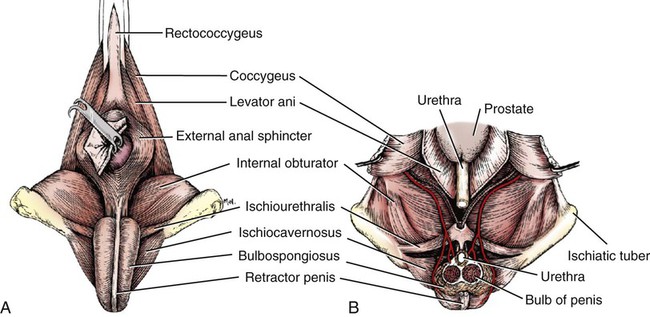

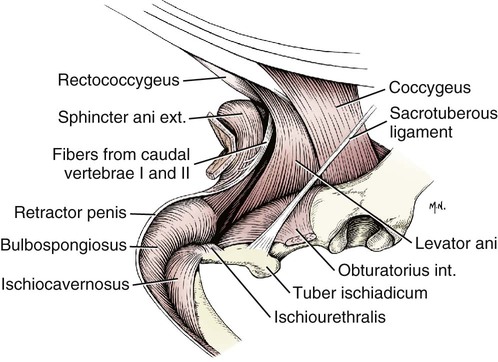

Male Genital Organs

Scrotum

Vessels and Nerves

Testes

Vessels and Nerves

Anomalies

Descent of the Testes

Epididymis

Structure

Ductus Deferens

Spermatic Cord

Prostate Gland

Vessels and Nerves

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The Urogenital System

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue