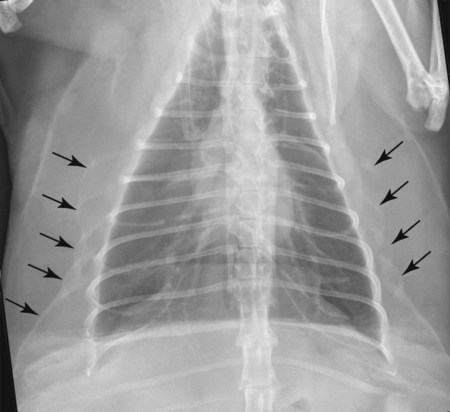

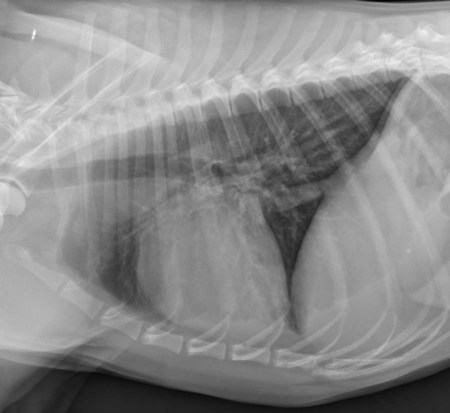

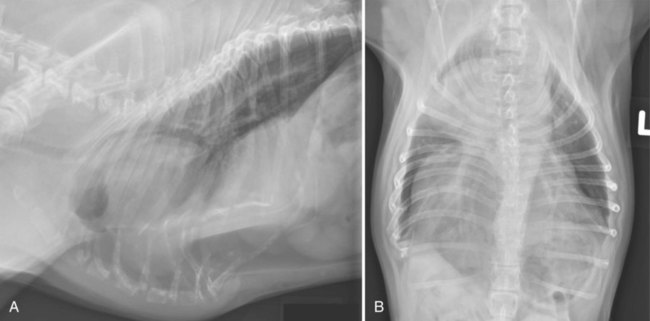

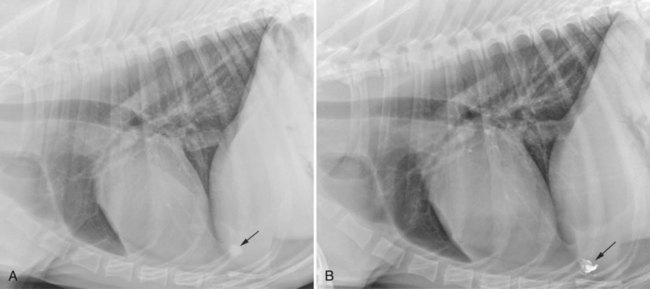

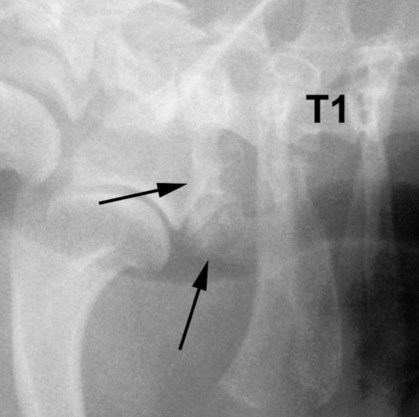

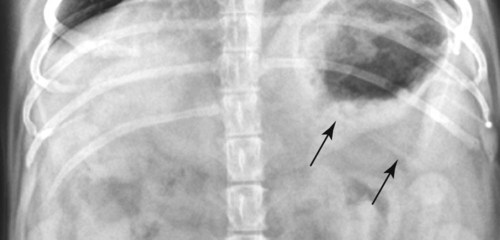

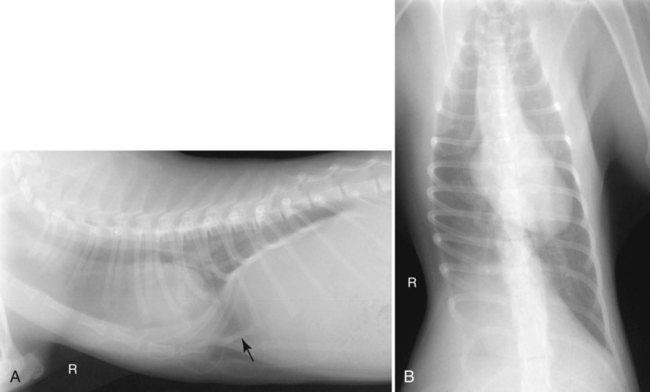

The soft tissues of the thoracic wall are normally homogeneous in opacity. In particularly obese animals, curvilinear soft tissue opacities, representing extracostal musculature outlined by fat, may be seen paralleling the lateral curvature of the ribs on dorsoventral (DV) and ventrodorsal (VD) projections (Fig. 28-1). Thirteen pairs of ribs and eight sternebral segments are normal. On the lateral projection, the first few ribs are oriented vertically but become progressively more caudoventral in orientation, from rib head to costochondral junction, in the mid to caudal aspect of the thoracic spine (Fig. 28-2). On the DV or VD projection, the first few ribs are oriented perpendicular to the spine. In the mid to caudal thoracic spine, ribs curve in a caudolateral direction from their respective vertebrae to their most lateral extent, then continue caudomedially (Fig. 28-3). Slight differences in thoracic wall conformation are common among various canine breeds (Fig. 28-4). Breed-associated costochondral conformation leading to a misdiagnosis of pneumothorax or pleural effusion is discussed in Chapter 31. Mineralization of the costal cartilages may be seen in young dogs and cats and is nearly always present in older animals (Fig. 28-5). Movement at the costochondral and costosternal joints increases as the costal cartilages stiffen from mineralization. This in turn results in osseous proliferation at the costochondral and costosternal joints. The opacities resulting from enlargement of these joints may be confused with lung nodules on DV or VD radiographs. Excessive costochondral or costosternal mineralization may also be confused with aggressive processes such as infection or neoplasia. Pedunculated soft tissue opacities on the thoracic wall, such as nipples, papillomas, or engorged ticks, may summate with the pulmonary parenchyma and be misdiagnosed as pulmonary nodules. Inspection and palpation of the thoracic wall surface usually clarify the significance of this finding. The inability to see the presumed pulmonary nodule in the lung on an orthogonal radiograph increases the likelihood of the suspicious opacity being caused by summation created by a superficial structure. Application of positive contrast medium, such as barium paste, on the thoracic wall nodule followed by repeat radiographs can be performed if localization is still in question (Fig. 28-6). Anomalies of the ribs and sternum are fairly common. Rudimentary ribs are sometimes present on the seventh cervical vertebra (Fig. 28-7) or the thirteenth thoracic vertebra (Fig. 28-8). Ribs may be hypoplastic or absent on the thirteenth thoracic vertebral segment (Fig. 28-9). These anomalies may be unilateral or bilateral (Fig. 28-10). The clinical significance of rib asymmetry at the thoracolumbar junction with regard to their use as a surgical landmark was discussed in the “Incidental Factors” section of Chapter 7. Congenital sternal deformities, such as reduction in number of segments, fusion of neighboring segments (Fig. 28-11), pectus carinatum (ventral displacement of the sternum), and pectus excavatum (funnel chest or dorsal displacement of the sternum) may be incidental findings, but some sternal anomalies have also been reported in animals with peritoneopericardial diaphragmatic hernia (Fig. 28-12).1,2 Peritoneopericardial diaphragmatic hernias are discussed in Chapter 29. Pectus excavatum (Fig. 28-13) results in dorsal to ventral narrowing of the thorax and is often associated with respiratory and cardiovascular anomalies. Although pectus excavatum may be congenital or acquired in human beings, all reports in animals describe congenital malformations.3 The etiology is unknown; however, a hereditary component has been suggested.4 Thoracic wall trauma is common in small animals but may go unnoticed. Direct soft tissue injury may produce soft tissue swelling or subcutaneous emphysema (Fig. 28-14), or air can accumulate because of leakage from the airway (Fig. 28-15). Tears of the intercostal musculature can result in separation of ribs and are a common sequela to bite wounds, resulting in uneven spacing between ribs (Fig 28-16).5,6

The Thoracic Wall

Normal Radiographic Appearance

Congenital and Developmental Abnormalities

Thoracic Wall Trauma

The Thoracic Wall