Chapter 47The Thigh

The Gluteal Syndrome

The Gluteal Syndrome

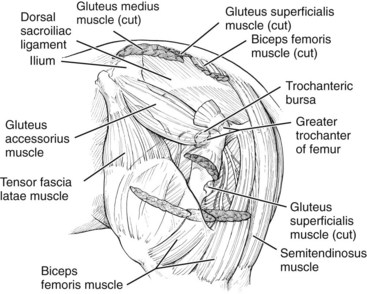

Based on dissections of cadavers, the accessory head of the middle gluteal muscle was identified as the deep structure that best corresponds anatomically to the characteristic pattern of pain. This muscle originates on the concave surface of the wing of the ilium near a tuber coxae. At its caudal extent, the accessory head of the middle gluteal muscle forms a flat tendon that passes over the cranial aspect of the greater trochanter of the femur and inserts on the crest below it. The accessory head is directly related to other aspects of the middle gluteal and superficial gluteal muscles superficially and is important in propulsion of the hindlimbs6 (Figure 47-1).

To date, the most reliable, practical method of diagnosis is by careful, systematic physical examination of the area between the wing of the ilium and the greater trochanter of the femur with the horse standing on the limb. More specifically, the musculature should be palpated and examined for changes in resilience, swelling, or fibrosis. The position and outline of the tuber coxae should be evaluated. Next, gentle, deep pressure should be applied along the entire area described with the tips of eight digits (Figure 47-2). Initially, light digital pressure should be applied, but then the pressure is gradually increased to firm, deep pressure. The pressure is maintained briefly to evaluate the horse’s response. Finally the area caudal to the ilium, the central portion, and the caudal part of the accessory head of the middle gluteal muscle should be examined similarly. Each third of the area should be considered separately to determine whether the area is affected generally or whether the injury is confined to one or more sections. An unaffected horse will not respond to the examination of any of the areas. An affected horse leans away from the pressure while showing a reluctance to voluntarily bear full weight on the limb as long as the pressure is maintained. A positive response for this syndrome as described is specific and should not be confused with that for trochanteric bursitis (see Trochanteric Bursitis section).

Fig. 47-2 Careful palpation for pain is the only way to establish the clinical diagnosis of gluteal syndrome.

Horses with this injury are best treated while in moderate, controlled exercise, regardless of the treatment approach. Rest alone, even for extended periods, has not been successful as a treatment. Several weeks of careful exercise management with repeated evaluations provide the best chance for a favorable response to treatment. Horses with acute injury, hemorrhage, and severe lameness should be rested until they are walking well and the seroma has resorbed before resuming exercise and treatment. Intramuscular injections of a counterirritant, acupuncture, and extracorporeal shock wave therapy are the best treatment options. At present, I still believe that injections of a counterirritant into the area of sensitivity yield the best results in the shortest time. The injection site is prepared with a surgical scrub followed by rinsing with 70% isopropyl alcohol. An injection grid is marked on the horse by drawing three lines in the wet hair over the accessory head of the middle gluteal muscle (Figure 47-3). One hundred milliliters of 2% iodine diluted in sesame oil solution is injected intramuscularly into 20 sites (5 mL/site) on and between the grid lines with a 4-cm, 19-gauge needle. If the pain is concentrated in the cranial or caudal third of the area between a tuber coxae and the ipsilateral greater trochanter of the femur, the injection sites can be limited to the cranial or caudal half of the area, respectively. After injection, daily moderate, controlled exercise is recommended beginning the day after injection for all horses. After injection, horses with acute or recent gluteal syndrome are walked and jogged for 3 weeks and then reexamined. If the lameness is improved but the area is still sensitive or if there has been no improvement, the injection is repeated in the same manner. Horses with chronic gluteal syndrome are walked and jogged for only 1 week before light training is resumed. Some horses respond dramatically to the treatment and appear to be pain-free within less than a week. The injury cannot heal within that time frame; therefore the temptation to resume full training too quickly must be resisted. When the treatment is successful and horses return to full work and racing, 10% to 20% may experience a recurrence of the problem. These horses generally respond well to an additional treatment as they did previously.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree