Chapter 21

The Spleen

The spleen is the second largest lymphoid organ.1 Splenic functions include initiation of immune-response to bloodborne antigens; storage of platelets and mature red blood cells (RBCs); maturation of reticulocytes; phagocytosis and destruction of senescent and damaged RBCs, platelets, and white blood cells (WBCs); phagocytosis of foreign particles and microorganisms; and extramedullary hematopoiesis.1,2 Because of these highly varied and often independent functions, different systemic inflammatory and noninflammatory diseases and hematologic disorders will impact the gross and microscopic appearance of the spleen in vastly different ways. As with other organs, the spleen is subject to cell growth disturbances (e.g., hyperplasia, hypoplasia), circulatory abnormalities (e.g., hemorrhage, congestion, thrombosis, and infarction), inflammation, and neoplasia (primary and metastatic).2 These processes, either alone or in combination, may result in splenic enlargement or changes in shape and echotexture.

Splenomegaly is usually detected by palpation or diagnostic imaging. Depending on the cause, splenomegaly may be accompanied by hematologic abnormalities such as anemia, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, and leukemia. A complete blood count (CBC) and careful examination of morphologies of RBCs, WBCs, and platelets in a peripheral blood film may be very revealing regarding causative factors. Causes of splenomegaly in dogs and cats are listed in (Table 21-1).2–7 Careful palpation and radiographic imaging should reveal the severity of splenomegaly and whether enlargement is diffuse or localized. Ultrasonographic examination provides a more detailed assessment of architectural abnormalities. By visualizing small nodules, target lesions, or changes in echogenicity in the spleen, ultrasonographic examination can reveal suspect areas of neoplasia, hyperplasia, inflammation, or extramedullary hematopoiesis and enables precise localization for fine-needle aspiration (FNA) or fine-needle biopsy (FNB).8–10

TABLE 21-1

CAUSES AND CHARACTERISTICS OF SPLENOMEGALY IN DOGS AND CATS

| Cause | Type of Enlargement | Severity of Enlargement |

| Hyperplasia | Symmetric or nodular | Mild to moderate |

| Infection | ||

| Immunologic disease | ||

| Extramedullary hematopoiesis | Symmetric or nodular | Mild to moderate |

| Hemolymphatic neoplasia | Symmetric | Moderate to severe |

| Lymphoma or lymphocytic leukemia | ||

| Myeloid neoplasms | ||

| Systemic mastocytosis | ||

| Plasma cell tumor or multiple myeloma | ||

| Other neoplasia | Symmetric or nodular | Mild to severe |

| Hemangioma or hemangiosarcoma | Nodular | |

| Fibrosarcoma or undifferentiated sarcoma | Nodular | |

| Histiocytic sarcoma | Nodular | |

| Hemophagocytic histiocytic sarcoma | Symmetric | |

| Leiomyoma or leiomyosarcoma | Nodular | |

| Metastatic neoplasms | Asymmetric or nodular | |

| Other | Symmetric or nodular | Highly variable |

| Systemic histiocytosis | ||

| Hemophagocytic syndrome | ||

| Fibrohistiocytic nodules | ||

| Hypereosinophilic syndrome | ||

| Inflammation | ||

| Circulatory disturbances | ||

| Hematoma | Asymmetric | Mild to moderate |

| Thrombosis with infarction | Symmetric | May not be enlarged |

| Portal hypertension with splenic congestion | Symmetric | Mild to moderate |

| Torsion | Symmetric | Severe |

Spangler WL, Culbertson MR: Prevalence and type of splenic diseases in cats: 455 cases (1985-1991), J Am Vet Med Assoc 201:773-776, 1992.

Indications for sampling of spleen are summarized in Box 21-1, but invasive collection of splenic tissue is not always needed if the cause is revealed by other means.11,12 For example, splenomegaly is likely linked to immune-mediated disease if a patient tests positive for erythrocytic antiglobulins (Coombs test), antinuclear antibodies, or rheumatoid factor. Serologic tests may suggest fungal or protozoal infections. Detection of hemoparasites such as Mycoplasma, Cytauxzoon, or Babesia spp. in a peripheral blood film also supports an infectious cause for splenomegaly. Cytologic examination of bone marrow or peripheral lymph nodes may enable diagnosis of hematopoietic and lymphocytic neoplasia or systemic infections. When splenomegaly is accompanied by peritoneal effusion collection and cytologic evaluation of abdominal fluid is indicated prior to direct sampling of the spleen.

Sampling Methods

Needle Methods

Collection of splenic samples by needle puncture should be carefully considered. An enlarged spleen may be turgid, friable, and engorged with blood. Profuse intraabdominal hemorrhage and tumor metastasis within the abdominal cavity are possible complications; however, several studies in dogs and humans concluded that thrombocytopenia, number of needle passes during collection, repeat collections, and core biopsies were not associated with an increase in the number or severity of complications.13–15

Fine-needle collections of the spleen can usually be done without general anesthesia. The size and location of the spleen within the abdominal cavity determine the actual site for penetration, which should be at the site where the spleen is most easily apposed to the abdominal wall. The site is prepared as if for surgery by clipping, washing, and applying an antiseptic. If the collection is aided by ultrasonographic imaging, care must be taken to not contaminate the skin, the slides, and the needles with lubricant, as this material stains a rich purple to magenta on slides and will interfere with microscopic evaluation (Figure 21-1). Infiltration of the abdominal wall with local anesthetic is usually unnecessary. A 22-gauge needle may be either directly attached to a 12-mL (milliliter) syringe for aspiration (FNA) or attached via an intravenous extension set for the nonaspiration method (FNB), which may reduce hemodilution of the sample, yield more highly cellular tissue fragments, and produce superior preparations.16–17 Needle length is determined by the size of the animal, but usually a 1- or 1½-inch needle is adequate.

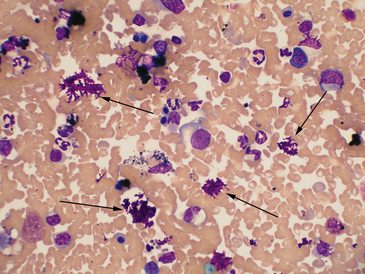

Figure 21-1 Canine spleen.

The arrows indicate deposits of magenta-stained material, typical for aqueous lubricant used for ultrasound-guided fine needle methods. Heavy contamination can prevent evaluation of a slide. (Wright-Giemsa. Original magnification 50× oil objective.)

For the FNB method, the needle is attached to an intravenous extension set, which is attached to the syringe.16 The syringe is filled with air prior to penetration of the skin and does not need to be handled during the actual collection of specimen, unlike the FNA method. After the spleen is penetrated, the needle tip is rapidly moved in and out 8 to 10 times without changing its path and without allowing the tip of the needle to leave the spleen. This will dislodge a small sample that will be retained within the bore of the needle. The needle is then withdrawn, and the specimen contained within the needle is immediately expelled onto a glass slide using the air-filled syringe. Prepare the smear as described below. This method usually results in only a single slide per penetration; therefore, three to five collections are suggested, each time targeting different areas of the spleen or splenic nodule.

The consistency of the specimen determines the method of smear preparation. Most specimens collected by the aspiration method have the consistency of blood and slides are prepared in the same manner as blood films. Specimens that are thick or contain tissue fragments, for example, specimens collected by FNB, are prepared by the squash technique, with the material gently compressed between two slides. Too much material on the slide can result in slides that are too thick to evaluate (Figure 21-2). Chapter 1 contains a detailed description of slide preparation techniques.

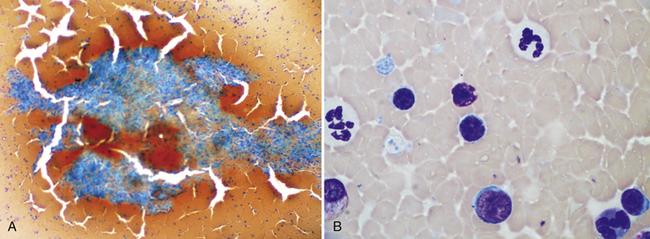

Figure 21-2 Canine spleen.

A, This preparation is very thick and cracked due to slow drying of the thick areas. The splenic tissue fragment cannot be evaluated and most of the dispersed nucleated cells are difficult to identify. In this type of preparation, it is difficult to distinguish small lymphocytes from larger potentially neoplastic cells. However, detection of these fragments confirms successful aspiration of spleen. (Wright-Giemsa. Original magnification 10× objective.) B, In some cases, the smear cannot be evaluated at all, but, as this image demonstrates, patient examination of thinner areas between fragments will be rewarded by finding cells spread thin enough to identify and evaluate. (Wright-Giemsa. Original magnification 100× oil.)

Impression, Scraping, and Squash Preparations

Impression, scraping, and squash preparations of splenic tissue may be prepared from biopsies taken during surgical exploration and often complement histologic assessment. In some situations, an immediate diagnosis may be obtained. For example, a homogeneous population of large lymphoblasts (Figure 21-3) or a pure population of mast cells (Figure 21-4) confirms a diagnosis of lymphoma and mast cell neoplasia, respectively. Cytologic preparations of splenic tissue reveal nuclear and cytoplasmic details not visible in tissue sections. The different tinctorial characteristics of hematologic stains allow more accurate identification of erythroid precursors versus lymphocytes, basophils versus histiocytes, and mast cells versus other round cells. Although tissue architecture is lost in collection, recognition of individual cell types, fungi, protozoa, RBC parasites, and neoplastic cells is sometimes easier on Wright-stained slides. Cytologic preparations are particularly valuable in identifying subtle dysplastic morphologies. However, changes attributable to circulatory disturbances as causes of splenomegaly, for example, congestion, hemorrhage, torsion, or infarction, are better assessed by histologic evaluation.

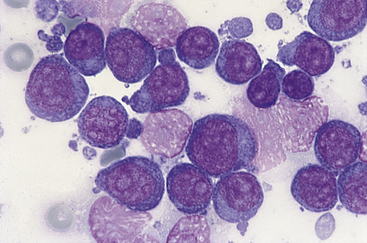

Figure 21-3 Canine spleen.

Impression smear prepared from a splenic biopsy from a dog with lymphoma contains a homogeneous population of large lymphocytes characterized by multiple prominent nucleoli. (Wright stain. Original magnification 100× oil objective.)

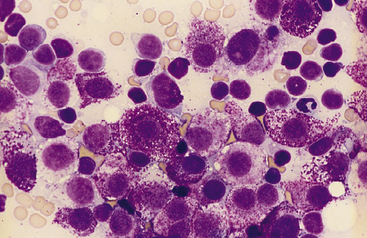

Figure 21-4 Feline spleen.

Impression smear prepared from a splenic biopsy from a cat with systemic mastocytosis and marked symmetric splenomegaly. The spleen is diffusely infiltrated with neoplastic mast cells that have round nuclei and numerous intracytoplasmic purple granules. Numerous small lymphocytes, plus a single neutrophil in the upper right corner, are also present. (Wright stain. Original magnification 100× oil objective.)

Preliminary to making impression and scraping smears from whole tissue specimens, blot the tissue on a paper towel to remove excess blood and fluid. If feasible, trim the tissue with a scalpel blade to expose a fresh-cut surface. Then make tissue imprints on the slides or scrape the surface with the scalpel blade and spread the scrapings on the slide. Also making squash preparations from tissue fragments should be considered. Using a variety of techniques increases the likelihood of getting smears that contain adequate specimen with good preservation of cell morphology. Further details are provided in Chapter 1.

Staining

Wright-Giemsa stain or a similar Romanowsky stain is the ideal stain for splenic cytology because it provides excellent definition of cytoplasmic features, facilitates identification of cytoplasmic granulation, and allows evaluation of hematopoietic cells. If using “quick” or “rapid” modified Wright stains, fixation and staining times will need to be increased for preparations that are thicker than blood films. Cytoplasmic granulation (e.g., granular lymphocytes, mast cells, myeloid precursors) may not be preserved with quick stains, although longer fixation times may ameliorate that problem to some extent. Chapter 1 contains specific information on staining techniques.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree