CHAPTER 39 The Reproductive Tract

Sexual Differentiation

Normal sexual differentiation depends on the successful completion of three consecutive events: establishment of chromosomal sex, gonadal sex, and phenotypic sex. Chromosomal sex (normally XX or XY) is established at fertilization and maintained by mitotic division after that. Sexual differentiation is completed by 46 days of gestation (Table 39-1), where gestation lengths are 65 days for dogs and 64 days for cats.

TABLE 39-1 Timeline of sexual differentiation in canine fetuses*

| Gestational age (Post-LH surge) | Sexual differentiation |

|---|---|

| 32 days | Female and male gonads undifferentiated |

| 36 days | Ovarian differentiation first detected in female embryos |

| 36 days | Testicular differentiation first detected in male embryos |

| 36 days | Müllerian duct regression in male embryos first observed |

| 42 days | Wolffian duct regression in female embryos first observed |

| 46 days | Müllerian duct regression in male embryos completed |

| 46 days | Wolffian duct regression in female embryos completed |

* Differentiation of fetal gonads and internal genitalia occurs between 32 and 46 days of gestation relative to the maternal preovulatory luteinizing hormone (LH) surge.

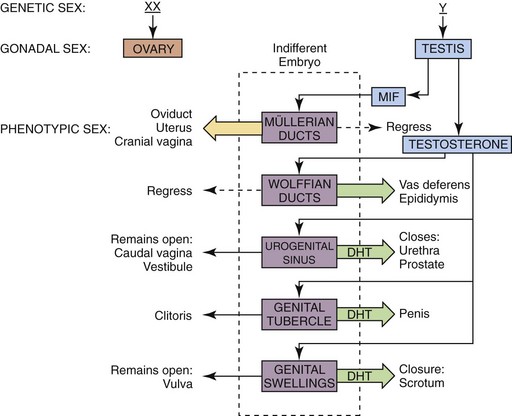

In the early embryo, the gonads are undifferentiated (Figure 39-1). Gonadectomy of XX or XY embryos before gonadal differentiation results in the development of a female phenotype, leading to the conclusion that the basic embryonic plan is female. A gene located on the Y-chromosome (Sry gene) encodes a testis-determining protein that results in testis formation and establishes the male gonadal sex. Sry acts as a master switch turning on several genes that are located on other chromosomes, thus inducing a cascade of gene products that are necessary for testicular development. In the absence of the Sry gene, the default pathway to female gonadal sex is initiated, and an ovary develops.

Following gonadal differentiation, development of the internal and external genitalia occurs. In the early embryo, both sets of internal tubular structures (wolffian and müllerian) develop initially. Two testicular secretions (müllerian-inhibiting factor [MIF] and testosterone) are responsible for masculinizing the tubular reproductive tract (see Figure 39-1). MIF, a glycoprotein produced by Sertoli cells, causes the müllerian (female) duct system (uterine tubes, uterus, cervix, and cranial vagina) to regress. Testosterone, a steroid hormone produced by Leydig cells, promotes the formation of the vas deferens and epididymides from the wolffian ducts. Testosterone is metabolized to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) within the cells of the urogenital sinus, the genital tubercle, and the genital swellings to result in the formation of the prostate and urethra, the penis, and the scrotum, respectively. Androgen-dependent masculinization is mediated through the binding of testosterone or DHT to the androgen receptor protein, the product of a gene on the X-chromosome.

Canine and feline male external genitalia originate from an undifferentiated urogenital tubercle (which forms at the level of the embryonic cloacal membrane). As a direct result of the influence of DHT, the prepuce develops from a circular plate of ectoderm invaginating at the level of the distal tip of the penis, whereas the junction between the preputial and penile mucosa (balanopreputial fold) dissolves at a later stage, also as a direct result of the action of androgens. In the absence of DHT (as in the normal female), the caudal vagina, vestibule, and vulva develop. Determination of gender in newborn dogs and cats may be difficult because the difference at this age is a slightly longer anogenital distance in males (13 to 15 mm) versus females (7 to 8 mm) (Figure 39-2). A pseudohermaphrodite is an animal that has the gonads of one sex with the internal and/or external genitalia and/or the chromosomal complement of the opposite sex (Box 39-1).

Testicular Descent

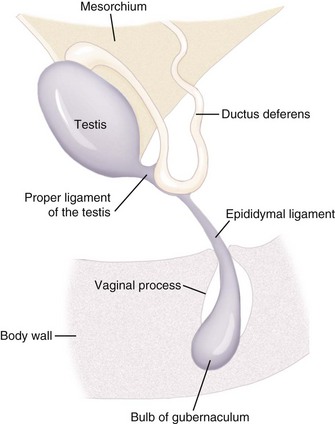

During fetal development, each testis moves to a position caudoventral to the inguinal canal from its original location near the caudal pole of the kidney. Testicular descent is coordinated by growth and regression of the gubernaculum. The gubernaculum extends from the caudal pole of the testis into the inguinal canal (Figure 39-3). Testicular descent occurs in three phases: intraabdominal, intrainguinal, and extrainguinal. During the intraabdominal migration, each testis moves toward its respective internal inguinal ring, and the caudal part of the gubernaculum enlarges enormously. The enlarging gubernaculum dilates the inguinal canal and extends the length of the scrotum, which facilitates the migration of the testis through the inguinal canal during the intrainguinal phase. In fact, the enlarged gubernaculum is present at birth and is frequently mistaken for descended testes in neonates. The extrainguinal phase is completed after birth in dogs and cats and involves regression of the gubernaculum, which guides/pulls the testis into the scrotum. Gubernacular outgrowth and enlargement are mediated by MIF. Testosterone plays a role in the regression of the gubernaculum and the terminal differentiation into the proper ligament of the testis and the ligament of the tail of the epididymis.

Figure 39-3 The normal relationship between the vaginal process, epididymal ligament, and gubernaculum.

(Redrawn from Peter AT: The reproductive system. In Hoskins JD (ed): Veterinary pediatrics: dogs and cats from birth to 6 months, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2001, Saunders, pp 463-475.)

Puberty

Most puppies and kittens attain puberty between 8 and 19 months of age, with a range of 4 to 22 months for both males and females (Table 39-2). At 2 months after birth, the ovary measures 5 mm in diameter. Environmental factors can affect the onset of puberty. Most female cats born early in the season or exposed when young either to tomcats or cycling females or to increasing amounts of light show the first signs of estrus before similar individuals born later or not exposed to these factors.

TABLE 39-2 Onset of puberty in the normal bitch and queen of reported breeds

| Species/Breed | Age at pubertal estrus |

|---|---|

| Canine | |

| Beagle | 7.2-23 months |

| Labrador Retriever | 7.2-16.3 months |

| Mongrel | 6.3-17.1 months |

| Feline | |

| Abyssinian | 7-14 months |

| Birman | 10-18 months |

| Burmese | 4-19 months |

| Himalayan | 4-16 months |

| Manx | 9-18 months |

| Siamese | 4-20 months |

| Domestic Shorthair | 4.5-15 months |

| Domestic Longhair | 6-18 months |

Modified from Johnston SD: Premature gonadal failure in female dogs and cats, J Reprod Fertil Suppl 39:65-72, 1989.

Reproductive Disorders in Male Pediatric Patients

Testicular Abnormalities

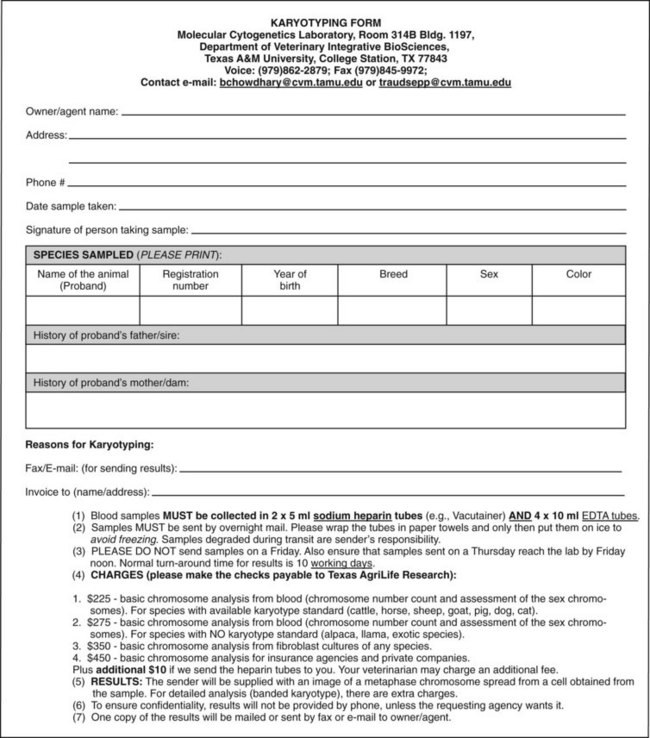

Congenital testicular abnormalities in cats and dogs include the congenital absence of one (monorchidism) or both (anorchidism) testes, testicular hypoplasia, and cryptorchidism. Puppies and kittens with XXY (Klinefelter’s) syndrome are phenotypically male, have a normal penis and prepuce, and have reportedly normal sexual behavior. Epididymides and small testis are present within the scrotum. However, ejaculates do not contain spermatozoa, and histologic evaluation of testicular tissue reveals seminiferous tubular dysgenesis with no evidence of spermatogenesis. More than one X-chromosome is deleterious to normal spermatogenesis. The XXY syndrome can arise by meiotic nondisjunction of the sex chromosomes during male or female gametogenesis or by mitotic nondisjunction in the early zygote. Nondisjunctional events leading to abnormal sex chromosome constitutions occur randomly and are not the result of a heritable defect. This syndrome is particularly well known; domestic shorthaired tomcats with this condition often feature a calico or tortoiseshell coat. In cats, the genes for orange and black coat color are X-linked alleles. Males with this coat color may also be XX/XY chimeras or XY/XY chimeras. In these two karyotypes, normal testicular histology and spermatogenesis may be present. A sample karyotype form is shown in Figure 39-4.

Figure 39-4 Sample karyotype form.

(Reproduced with kind permission from Drs. B.P. Chowdhary (Director) and T. Raudsepp (Associate Director) of the Molecular Cytogenetics Laboratory at the College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Texas A&M University.)

Failure of the testis to descend into the scrotum (cryptorchidism) is a development defect. Unilateral cryptorchidism is 4 times more common than bilateral cryptorchidism. If only one scrotal testis is present, careful ultrasonographic or surgical exploration of the contralateral inguinal canal and abdomen may be necessary to determine whether the missing scrotal testis is retained, hypoplastic, or absent. Inguinal retention is 3 times more likely than abdominal retention. For abdominal retention, tracing the vas deferens retrograde from its insertion on the dorsal aspect of the prostate is a useful method to find the testis. Cases of bilateral cryptorchidism can be distinguished from anorchidism postpubertally using challenge testing (Box 39-2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree