The Phylum Platyhelminthes, Class Cestoda

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, the reader should be able to do the following:

• Briefly discuss the external morphology of cestodes.

• Describe the four types of cestode eggs.

• Compare the life cycle of a typical true tapeworm with that of a typical pseudotapeworm.

• Be able to integrate vocabulary terms with the cestode parasites covered in Chapter 6.

Key Terms

Cestode

True tapeworm

Pseudotapeworm

Proglottid

Scolex

Acetabula, suckers

Tegument

Rostellum

Armed tapeworm

Unarmed tapeworm

Neck

Immature proglottid

Mature proglottid

Gravid proglottid

Hermaphroditic

Hexacanth embryo

Metacestode stage

Cysticercoid

Cysticercus

Coenurus

Hydatid cyst

Tetrathyridium

Bothria

Coracidium

Copepod

Procercoid

Plerocercoid

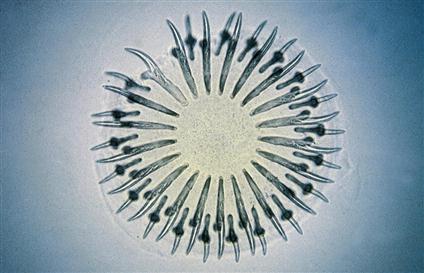

The phylum Platyhelminthes, the flatworms, includes the trematodes (or flukes) discussed in Chapters 7 and 8, and the cestodes (or tapeworms) detailed in this chapter and Chapter 6. Remember that the morphologic feature shared by these two classes is that they are both dorsoventrally flattened. However, whereas the flukes are flattened and leaf-shaped, the tapeworms are ribbonlike and segmented into identical compartments called proglottids (Figure 5-1).

Members of the phylum Platyhelminthes, class Cestoda, are often referred to as cestodes or “tapeworms.” Their bodies are usually long, segmented, and flattened, almost ribbonlike in appearance. Within the class Cestoda are two subclasses, the subclass Eucestoda (true tapeworms) and the subclass Cotyloda (pseudotapeworms). Members of both of these classes are important parasites of domesticated and wild animals and of humans.

Eucestoda (True Tapeworms)

Key Morphologic Features

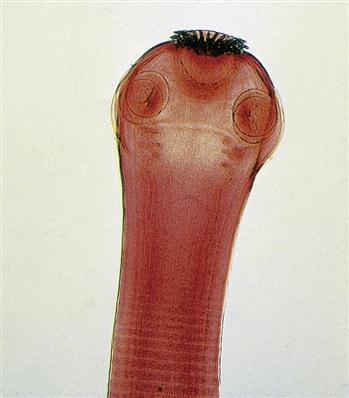

As mentioned, tapeworms are long, segmented, flattened, almost ribbonlike parasites. On the extreme anterior end of the typical true tapeworm is the holdfast organelle, the scolex, or head (Figure 5-2). The scolex of the adult true tapeworm has four suckers called acetabula, with which the tapeworm holds on to the lining of the small intestine, the predilection site, or “home,” of most adult tapeworms. Unlike the oral sucker of the digenetic trematode, the suckers of the true tapeworm are not associated with intake of food but rather serve as organs of attachment. True tapeworms do not have a mouth; instead, they absorb the nutrients acquired from the host’s intestine through their tegument, or body wall. In addition to the suckers, some true tapeworms may possess an anchorlike organelle called the rostellum (Figure 5-3). The rostellum usually has backward-facing hooks. With these hooks, the tapeworm further anchors itself in the mucosa of the small intestine. If the tapeworm has a rostellum, it is said to be an armed tapeworm; if the tapeworm lacks the rostellum, it is said to be an unarmed tapeworm.

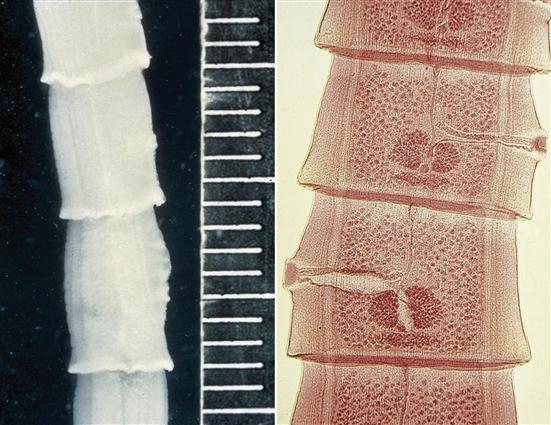

Just posterior to the scolex of the true tapeworm is a germinal, or growth, region called the neck. It is from the neck that the rest of the true tapeworm’s body, the strobila, arises. The strobila is composed of individual proglottids that are arranged similar to the boxcars in a railroad train. The proglottids closest to the scolex and the neck of the true tapeworm are the immature, or youngest, proglottids (Figure 5-4); those that are intermediate in distance from the scolex and the neck are the mature proglottids (Figure 5-5); and those farthest from the scolex and the neck are the gravid, or oldest, proglottids (Figure 5-6).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree