Chapter 108The North American Standardbred

Description of the Sport

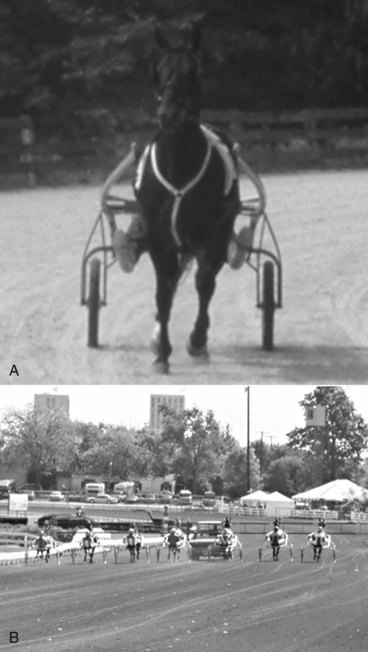

The STB races at two different gaits: the trot, a diagonal two-beat gait in which the left forelimb (LF) and right hindlimb (RH) move together, and the pace, a lateral two-beat gait in which the LF and left hindlimb (LH) move together. High knee action and a lateral (left to right) nodding of the head are typical of a trotter (Figure 108-1, A). A trotter travels straight ahead (see Figure 108-1, A) (Figures 108-2, A, and 108-3), but a pacer sways from side to side while moving forward (see Figure 108-1, B).

Amateur STB driving and racing under saddle are hobby-type events that are increasing in popularity. STBs compete at horse shows in the roadster classes, hitched to a bike or wagon, and also as road horses under saddle. Former STB racehorses are not only popular in the Amish community, but they also can be found performing diverse sporting activities such as low-level dressage and jumping. The Standardbred Retirement Foundation (http://www.adoptahorse.org) helps to find homes for former racehorses; the Harness Racing Museum and Hall of Fame (http://www.harnessmuseum.com) and the United States Trotting Association (http://www.ustrotting.com) are worthy causes and valuable sources of information about the North American STB.

Training

A STB is trained in a jog cart that is stronger, longer, and about three times as heavy as the 14-kg sulky or race bike. A young pacer is soon equipped with hobbles, which are leather or plastic straps encircling the ipsilateral forelimbs and hindlimbs, to keep legs moving in unison (see Figure 108-1, B). A horse capable of sustaining a pace without hobbles is called a free-legged pacer, but few race without hobbles. Hobbles can cause areas of hair loss on the cranial aspect of the forearm and the caudal aspect of the crus called hobble burns, which are typical marks of a pacer. Trotting hobbles, which are straps encircling both forelimbs that run through a pulley underneath the horse, have become popular and are being used on more and more trotters in recent years, even those competing in top stakes races. Trotting hobbles may stabilize the trotting gait at speed. Some in the industry frown on the use of these equipment additives, claiming they may give an unfair advantage and historically have not been used.

Track Size and Lameness

Track size has substantial implications in the development and expression of lameness. Tracks are 1 mile,  mile,

mile,  mile, and

mile, and  mile, and in general race times are lower (faster) on large tracks. Because most STB races are 1 mile, track size determines the number of turns during the race. During a race on a

mile, and in general race times are lower (faster) on large tracks. Because most STB races are 1 mile, track size determines the number of turns during the race. During a race on a  -mile track, a STB must negotiate four turns. Turns on smaller racetracks are much tighter than those on larger tracks (see Figure 108-2). There is a single racetrack larger than a 1-mile oval, Colonial Downs in Virginia, at which a short race meet is held each year; on this track, races involve negotiating a single turn. Horses racing with mild chronic lameness are less likely to sustain speeds necessary to be competitive on larger tracks, so they may race on smaller tracks; however, if lameness is worse in the turns, the horse may be less competitive on small tracks and better suited for a 1-mile track. If lameness is worse in the straightaway, the horse may be best suited for a small track. This is particularly important when lameness worsens as the race goes on because large tracks have a long straightaway at the end.

-mile track, a STB must negotiate four turns. Turns on smaller racetracks are much tighter than those on larger tracks (see Figure 108-2). There is a single racetrack larger than a 1-mile oval, Colonial Downs in Virginia, at which a short race meet is held each year; on this track, races involve negotiating a single turn. Horses racing with mild chronic lameness are less likely to sustain speeds necessary to be competitive on larger tracks, so they may race on smaller tracks; however, if lameness is worse in the turns, the horse may be less competitive on small tracks and better suited for a 1-mile track. If lameness is worse in the straightaway, the horse may be best suited for a small track. This is particularly important when lameness worsens as the race goes on because large tracks have a long straightaway at the end.

Conformation

A serious hindlimb fault leading directly to moderate to severe lameness is sickle-hocked conformation (see Chapters 4 and 78). Mild sickle-hocked conformation typified many early pacers and is desired by some trainers. Sickle-hocked trotters are fast but develop curb and osteoarthritis (OA) of the distal hock joints, particularly severe in the dorsal aspect, and are chronically unsound. Sickle-hocked conformation predisposes all STBs to the development of slab fractures of the third and central tarsal bones. Straight hindlimb conformation is unusual but is a severe fault, leading to metatarsophalangeal and stifle joint lameness and suspensory desmitis. In horses with straight hindlimb conformation, excessive extension of the metatarsophalangeal joint occurs. Long, sloping pasterns also predispose horses to fetlock hyperextension, but a primary metatarsophalangeal joint weakness is seen in some trotters with normal pastern lengths, in which the base of the proximal sesamoid bones (PSBs) is level with the middle of the proximal phalanx. Abnormal elasticity or loss of support from the suspensory apparatus predisposes horses to run-down injury and suspensory desmitis. Run-down injury is more commonly seen in the hindlimbs. Cow-hocked conformation is prevalent in trotters but is not problematic unless severe. In-at-the-hock conformation predisposes horses to OA of the distal hock joints, curb, and medial splint bone disease. Base-wide and base-narrow conformational faults, if severe, can lead directly to interference and lameness.

Distribution of Lameness

STB racehorses have a higher percentage of hindlimb lameness than TBs. The STB trains and races using a two-beat gait: two limbs bear weight simultaneously. Load is shared almost equally between forelimbs and hindlimbs. The caudal location of the cart and driver (load) and the addition of the overcheck apparatus shift the center of balance caudally, increasing hindlimb lameness (see Figure 2-2Figure 2-3). The distribution of forelimb to hindlimb lameness is approximately 55% to 45%.

Lameness in the Young Standardbred

The top 10 list (see page 1024) contains those conditions seen in STB racehorses of all ages when grouped together, but unraced 2- and early 3-year-olds develop a subset of lameness conditions. Osteochondrosis (see Chapters 54 and 56), splint exostoses (splints), and curbs are common. Forelimb splints are usually medial but can occur laterally. Hindlimb splints are almost always medial and are more common in trotters. Splints can cause primary lameness or be secondary to carpal lameness, especially if the exostosis is proximal. Forelimb splints develop when the limb is carried or lands abnormally. Young horses develop splints from difficulty learning the racing gait and by making breaks. While breaking, pacers often hit themselves because galloping in hobbles is difficult. Curb is common in young pacers and may be recognized while horses are jogging, before training begins (see Chapter 78).

Interference injuries are common and plague many STBs throughout the racing career. Trotters interfere primarily by striking the toe of the ipsilateral front foot to the shin, pastern, or coronary band regions of the hindlimb (see Chapter 7 and Figure 7-2). Interference from a front foot striking the medial aspect of the contralateral forelimb (cross-firing) occurs occasionally in trotters but is a major form of interference injury in pacers. Injury to second (McII) and third metacarpal (McIII) bones, PSBs, carpus, heel, and hoof wall causes bruising and hematoma formation. Contusions can lead to soreness or frank lameness and can cause an altered gait. A trotter attempting to avoid striking the LH shin shortens the cranial phase of the stride, causing what appears to be a pelvic hike, mimicking LH lameness. Deliberate hiking can alter load distribution, causing compensatory lameness in the RH and RF. Local trauma is treated, and changes in equipment and shoeing, such as applying brace bandages and boots, are performed. A brief (5 to 7 days) reduction in exercise intensity is useful to allow a young horse to gain confidence in the corrected gait.

Young horses with poor gait should be examined carefully for neurological disease. Equine protozoal myelitis (EPM) is endemic in STBs and can be a real cause of gait deficits or a catchall diagnosis (see Chapter 11).

Clinical History

Is the horse on a line? This is one of the most important pieces of information to obtain. Trainers sometimes dismiss young horses being mildly on the line because nervous and inexperienced horses may change directions suddenly, but in reality most of these abnormal movements are caused by lameness. During counterclockwise racing of a horse on the right line, the driver has to increase the tension (pull harder) on the right rein to keep the horse straight and prevent it from bearing toward the infield. Just the opposite occurs when horses are on the left line (see Figure 108-3). Because of bit pressure, when a horse is on the left line, it turns or cocks the head to the left, toward the inside rail, and vice versa. If history is unclear, the veterinarian should watch the horse on the track and observe head position. Because most horses bear away from pain, a horse on the right line is most often lame on the right side, but exceptions occur. A common finding is metacarpophalangeal effusion and a positive response to lower limb flexion. The trainer states, “The horse was on the left line when finishing the mile, but is usually on the right line especially in the turns.” Primary lameness may be in the right carpus, but chronic RF lameness has caused compensatory overloading and lameness of the left metacarpophalangeal joint, and both areas should be evaluated and potentially treated. Most horses on a line from forelimb lameness have foot or carpal lameness. However, problems located medially, such as medial sole bruising, quarter cracks, or carpal lameness, paradoxically can cause a horse to be on the contralateral line. Horses may lose power in the affected limbs and drift at speed toward the lame side. Therefore a horse with a medial LF quarter crack could be on the right line, whereas those with a right carpal lameness could be on the left line. All limbs should be examined because not all horses read the book. “If a horse is on the left line, think right hind,” one old saying goes, and rarely a horse with RH bruised or cracked heels will be on the left line.4

Is the horse on a shaft? A horse with RH lameness drifts to the left (see Figure 108-2) and positions the hindquarters closer to the left shaft of the sulky and is thus on the left shaft; the reverse is true with LH lameness (see Figure 108-3). Not all hindlimb lameness problems cause horses to be on a shaft. Horses with OA of the medial femorotibial joint may not be on a shaft, but those with distal hock joint pain will be. A horse may be falsely on a shaft if it is hard on a line and the driver pulls hard to keep the horse straight, compelling the horse to twist its entire body, positioning the hindquarters close to one shaft to maintain balance.

On what size track does the horse race? The relationship of track size to expression of lameness and the differences between left- and right-sided lameness problems were discussed (see page 1017).

Lameness Examination

Palpation

Careful palpation is the art of diagnosis in the racehorse but often is sacrificed because palpation is time consuming. Palpation is critical in STBs because of numerous compensatory lameness problems. The veterinarian needs to be able to “read” the horse to make a diagnosis. A successful lameness detective respects what the horse is trying to say. The veterinarian should move over the entire horse with a light touch to see whether a withdrawal response is elicited. A light touch along the neck and gluteal regions may elicit pain from secondary muscle soreness or painful previous intramuscular injection sites. Horses often exhibit a withdrawal response when a limb is first picked up, indicating a problem even before the specific region is manipulated. Horses may exhibit false-positive responses in areas that have been recently painted, blistered, or freeze fired. Once horses have been freeze fired for splints and curbs, many trainers assume the problem has been solved and are incredulous if the veterinarian suggests the area is still the source of pain. Cryotherapy is not a panacea and may have to be repeated, or another form of management may be needed (see Chapters 78 and 89).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

years of age and begin racing the next summer. Many states have racing programs for 2-, 3-, and 4-year-old horses and require a horse to be nominated early in life. Eligibility then is maintained by periodic payments, called stake payments, creating a large pool of money divided among the winners of elimination and final events. Although some stake races receive track or corporate purse assistance, owners who put up their own money support most races. Stake races are limited by age and sex. For example, 2-year-old trotting fillies race together. Stake payments must be made early in the spring, before talent and speed of individual horses can be confirmed, and owners, trainers, and veterinarians must decide which horses to stake. Emphasis on racing young STBs and the money necessary to maintain stakes eligibility place extreme pressure on trainers to race horses at 2 and 3 years of age. Horses often are pushed farther and faster than is reasonable, placing them at risk of stress-related bone injury, usually of subchondral bone. Many owners do not realize the difficulty of having a horse compete based on a calendar of scheduled events, expecting the horse to peak for the biggest purses, rather than on the horse’s training and fitness level. The process of nominating and planning for stakes races is an art and science, and often a staking service is hired to organize periodic stake payments. Stake payments are a considerable expense, and some owners spend several hundred thousand dollars a year. Horses not nominated, those dropped from stakes programs because of injury or lack of talent, or those in which payments were missed are still eligible for overnight racing. More and more late closer and entry-only stakes are becoming available for nonstaked horses.

years of age and begin racing the next summer. Many states have racing programs for 2-, 3-, and 4-year-old horses and require a horse to be nominated early in life. Eligibility then is maintained by periodic payments, called stake payments, creating a large pool of money divided among the winners of elimination and final events. Although some stake races receive track or corporate purse assistance, owners who put up their own money support most races. Stake races are limited by age and sex. For example, 2-year-old trotting fillies race together. Stake payments must be made early in the spring, before talent and speed of individual horses can be confirmed, and owners, trainers, and veterinarians must decide which horses to stake. Emphasis on racing young STBs and the money necessary to maintain stakes eligibility place extreme pressure on trainers to race horses at 2 and 3 years of age. Horses often are pushed farther and faster than is reasonable, placing them at risk of stress-related bone injury, usually of subchondral bone. Many owners do not realize the difficulty of having a horse compete based on a calendar of scheduled events, expecting the horse to peak for the biggest purses, rather than on the horse’s training and fitness level. The process of nominating and planning for stakes races is an art and science, and often a staking service is hired to organize periodic stake payments. Stake payments are a considerable expense, and some owners spend several hundred thousand dollars a year. Horses not nominated, those dropped from stakes programs because of injury or lack of talent, or those in which payments were missed are still eligible for overnight racing. More and more late closer and entry-only stakes are becoming available for nonstaked horses. to 1 mile in circumference; a 1-mile track is most common. Races are usually 1 mile, but a few are

to 1 mile in circumference; a 1-mile track is most common. Races are usually 1 mile, but a few are  -mile sprints to 2-mile races. The track surface is a crushed rock base, covered with a packed, sandy soil and a thin sand or stone dust surface. STB racing requires a much firmer track surface than galloping horses. Sulky tires are more efficient if rolling over a firm smooth surface, and the STB gaits require a firmer and smoother surface than does the gallop. Track surfaces have become firmer because year-round racing requires a surface suitable for racing in rain and subfreezing temperatures. Hard tracks with loose surfaces require horses to wear shoes with added grabs and welded-on spots of borium to avoid slipping. Excessive slipping or overzealous use of shoes with additives predisposes horses to lameness. A soft or deep surface can predispose horses to tendonitis and suspensory desmitis. Hard tracks with a covering of loose stone dust are slippery and may predispose horses to carpal synovitis, bruised soles, and muscle soreness. Racetracks get soft and sticky with small amounts of rain and hard and unyielding with heavy rainfall that may wash the top surface into the infield. Recently, a three-dimensional dynamometric horseshoe was used to measure acceleration and other forces on the front hoof of French trotters performing at high speed on two different track surfaces, all-weather waxed and crushed sand track surfaces.1,2 Hoof deceleration was significantly less, and there was a 50% attenuation of shock when horses performed on the waxed surface, suggesting this surface had better shock-absorbing qualities compared with a crushed sand surface.1 The amplitude of the maximal longitudinal braking force was significantly lower and occurred 6% later in the stance phase. The magnitude of the ground reaction force at impact was lower on the waxed track compared with the crushed sand track surface.2 The attenuation of loading rate, amplitude of horizontal braking, and shock at impact on waxed surfaces suggested that there is likely a reduction in stress in the distal aspect of the forelimb, results that may be important in training normal horses or rehabilitating STBs with infirmities.2

-mile sprints to 2-mile races. The track surface is a crushed rock base, covered with a packed, sandy soil and a thin sand or stone dust surface. STB racing requires a much firmer track surface than galloping horses. Sulky tires are more efficient if rolling over a firm smooth surface, and the STB gaits require a firmer and smoother surface than does the gallop. Track surfaces have become firmer because year-round racing requires a surface suitable for racing in rain and subfreezing temperatures. Hard tracks with loose surfaces require horses to wear shoes with added grabs and welded-on spots of borium to avoid slipping. Excessive slipping or overzealous use of shoes with additives predisposes horses to lameness. A soft or deep surface can predispose horses to tendonitis and suspensory desmitis. Hard tracks with a covering of loose stone dust are slippery and may predispose horses to carpal synovitis, bruised soles, and muscle soreness. Racetracks get soft and sticky with small amounts of rain and hard and unyielding with heavy rainfall that may wash the top surface into the infield. Recently, a three-dimensional dynamometric horseshoe was used to measure acceleration and other forces on the front hoof of French trotters performing at high speed on two different track surfaces, all-weather waxed and crushed sand track surfaces.1,2 Hoof deceleration was significantly less, and there was a 50% attenuation of shock when horses performed on the waxed surface, suggesting this surface had better shock-absorbing qualities compared with a crushed sand surface.1 The amplitude of the maximal longitudinal braking force was significantly lower and occurred 6% later in the stance phase. The magnitude of the ground reaction force at impact was lower on the waxed track compared with the crushed sand track surface.2 The attenuation of loading rate, amplitude of horizontal braking, and shock at impact on waxed surfaces suggested that there is likely a reduction in stress in the distal aspect of the forelimb, results that may be important in training normal horses or rehabilitating STBs with infirmities.2