Chapter 36 The Metacarpophalangeal Joint

Anatomical Considerations

The digital flexor tendon sheath and its contents are described elsewhere (see Chapter 74). The common digital extensor tendon is unsheathed as it passes over the dorsal aspect of the joint. Branches of the medial and lateral palmar and metacarpal nerves primarily supply innervation to the fetlock joint,3 but small subcutaneous branches of the ulnar nerve supply a minor amount of dorsal sensory innervation.

Diagnosis

Careful physical examination to detect heat, swelling (effusion with or without periarticular fibrosis), and pain with palpation or manipulation is critical for diagnosis of lameness of the metacarpophalangeal joint. However, physical findings may be subtle or seemingly nonexistent, whereas diagnostic analgesia often pinpoints the joint or region as the source of pain. Interpretation of fetlock flexion test results should be made with caution because many horses have false-positive responses to forced flexion of this joint, especially if the toe is used to increase leverage. Pain originating in the limb distal to the fetlock joint often is exacerbated by fetlock or lower limb flexion tests. False-negative responses to fetlock joint flexion also are common, especially in horses with subchondral bone injury and chip fractures. Flexion tests are discussed further in Chapter 8. Increased fluid in the fetlock joint can also be a false localizing sign. The presence of an effusion in the absence of heat and pain may indicate some derangement in synovial function but not necessarily point to the source of a clinically relevant lameness. Lameness characteristically occurs with weight bearing and usually, but not always, is worse with the limb on the inside of a circle. If clinical signs do not adequately localize lameness, perineural or intrasynovial analgesia can specify the region relatively easily. In the absence of localizing clinical signs, the foot and pastern regions should first be eliminated as sources of pain by a midpastern digital nerve block with a dorsal subcutaneous ring. Ideally this is followed by intraarticular analgesia of the metacarpophalangeal joint. If the lameness does not improve within 15 to 20 minutes of intraarticular analgesia, the clinician should perform a low palmar block or palmar and palmar metacarpal nerve blocks. In most horses with intraarticular chip fractures, synovitis, capsulitis, and osteoarthritis (OA), lameness improves after intraarticular analgesia. Horses with major fractures, nonarticular fractures, subchondral bone injuries, and tendon and tendon sheath lesions usually are only markedly improved with perineural analgesia. Perineural techniques are superior to definitively abolish pain associated with the fetlock joint. Pain in horses that do not respond to intraarticular analgesia should not necessarily be presumed to originate elsewhere. False-positive results to intraarticular analgesia can also be obtained; lameness associated with a suspensory branch injury or injury of the proximal aspect of the oblique, cruciate, or straight sesamoidean ligaments may be substantially improved or abolished. Subchondral bone pain will not always, or completely, be eliminated with intraarticular analgesia.

Several techniques are used for intrasynovial analgesia of the fetlock joint. One author (DWR) prefers to inject the local anesthetic solution with the horse’s limb on the ground. The dorsal aspect of the fetlock is readily accessible when the horse is bearing weight. As the clinician faces forward and presses the back of his or her arm against the horse’s carpus, a 22-gauge, 2.5-cm needle attached to a 75-cm extension set is inserted horizontally into the dorsal aspect of the joint just proximal to the margin of the proximal phalanx and deep to the common digital extensor tendon. One of us (DWR) uses 10 to 15 mL of 2% mepivacaine, but many practitioners use no more than 6 to 10 mL. One author (SJD) prefers to inject into the palmar pouch through the metacarposesamoidean ligament, with the limb flexed, using a 21-gauge, 3.8-cm needle, injecting 6 to 10 mL of 2% mepivacaine depending on the size of the horse. Other techniques are described in Chapter 10.

Imaging Considerations

Ultrasonographic evaluation of the fetlock can be valuable for evaluation of tendon and ligament injuries around the fetlock, especially the digital flexor tendons, the palmar annular ligament (see Chapter 74), and the dorsal synovial pad/plica, as well as the bone margins.10,11 Ultrasonography (96%) was more accurate than radiology (44%) in predicting the number and location of osseous fragments on the dorsal aspect of the metacarpophalangeal and metatarsophalangeal joints identified using arthroscopy.12 Three-dimensional imaging modalities such as computed tomography (CT)13-15 (see Chapter 20) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (see Chapter 21) can also be very valuable in the fetlock, especially in areas like the distal palmar McIII condyle, the axial aspect of the PSBs, and the periarticular soft tissues.16-19

Types of Fetlock Joint Lameness

Most fetlock joint lamenesses can be categorized into one of three types:

Conditions specific to the metatarsophalangeal joint and a detailed description of sagittal fractures of the proximal phalanx are discussed elsewhere (see Chapters 35 and 42). Injuries of the digital flexor tendon sheath, superficial and deep digital flexor tendons, the palmar annular ligament, and the proximal digital annular ligament are discussed in Chapter 74. Suspensory ligament (SL) branch injuries are discussed in Chapter 72. Injuries of the distal sesamoidean ligaments are discussed in Chapter 82. Traumatic disruption of the suspensory apparatus is discussed in Chapter 104.

Acute or Repetitive Overload Injuries

Chronic Proliferative (Villonodular) Synovitis

Clinical Signs

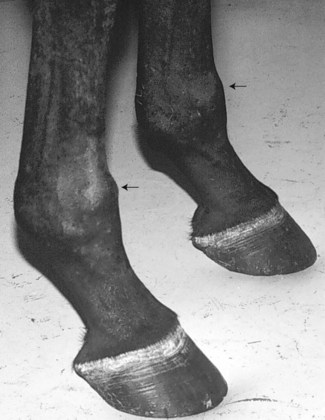

Chronic capsulitis/synovitis is caused by repetitive injury of the dorsal aspect of the fetlock joint. The lesion is defined by a thickening of the normally dorsally located bilobed synovial pad that hangs down on either side of the sagittal ridge of the McIII. With extreme extension of the fetlock joint, the dorsal rim of the proximal phalanx impinges on the synovial pad, and repetitive trauma results in its inflammation and subsequent fibrosis. The tissue can become so thick that the dorsal profile of the joint is visibly disfigured. The characteristic swelling is asymmetrical on the midproximodorsal aspect of the fetlock (Figure 36-1) rather than simply spherical in outline as in a typical osteoarthritic fetlock joint (this is called an osselet). Exercise inflames the tissue further, and clinical signs of lameness or diminished performance can result.

Diagnosis

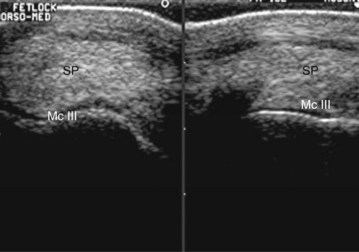

The diagnosis of proliferative synovitis is based on physical examination, radiography, ultrasonography, or a combination of these modalities. The most common radiological sign of the lesion is a crescent-shaped, radiolucent “cut-out” on the dorsal aspect of the McIII at the level of the joint capsule attachment (Figure 36-2). The proliferative lesion may undergo dystrophic mineralization and be radiologically visible. Radiographic contrast studies can be used, but ultrasonography is simpler and more reliable (Figure 36-3). Normal thickness on ultrasonographic examination has been described as less than 2 mm,10,11 but mere identification of a slightly thicker than average structure is certainly not an indication for surgical excision. Many older racehorses have a substantially thicker synovial pad without any associated discomfort. Horses with severe OA have proliferative synovitis in the palmar pouch, and a large concave outline of the distal palmar aspect of the McIII is seen proximal to the PSBs (Figure 36-4 and Figure 34-17), which is associated with a poor prognosis.