Chapter 8 The Genus Corynebacterium

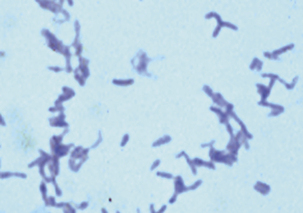

Members of the genus Corynebacterium are actinomycetes that are related to the genera Mycobacterium, Nocardia, and Rhodococcus. The genus comprises aerobic gram-positive pleomorphic rods (Figure 8-1), often with a coccoid or club-shaped appearance, called diptheroidal after Corynebacterium diphtheriae, the agent of human diphtheria. Corynebacterium aquaticum is motile, but the remaining species in the genus are nonmotile. They are aerobic or facultatively anaerobic, catalase positive, non–spore forming and non–acid fast, with little tendency to branch. The cells walls of corynebacteria are singular in structure and composition; they are, in large part, the basis for the organism’s ability to survive under adverse environmental conditions, including the skin. They contain corynemycolic acids, which are granulomagenic and may mediate intracellular survival.

Corynebacterium diphtheriae and Corynebacterium ulcerans are prominent human pathogens. Arcanobacterium (Actinomyces, Corynebacterium) pyogenes, Actinobaculum (Actinomyces, Eubacterium, Corynebacterium) suis, and Arcanobacterium (Corynebacterium) haemolyticum are former members of the genus. The notable animal pathogens (Table 8-1) are Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis, a cause of lymphadenitis and lymphangitis in small ruminants and horses, respectively, and Corynebacterium renale (cystitidis, pilosum), opportunist agents of urinary tract infections in cattle and occasionally other species. Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis and C. ulcerans can produce diphtheria toxin when lysogenized by corynephage β-bearing tox.

TABLE 8-1 Corynebacteria Encountered in Veterinary Medicine

| Corynebacterium Species | Disease |

|---|---|

| C. diphtheriae | Human diphtheria; bovine mastitis and dermatitis (infrequent); isolated from an equine wound infection |

| C. renale | Bladder, kidney infections in cattle and swine; penis infections (pizzle rot) in castrated sheep; rare bladder infections in the dog; osteomyelitis in goats |

| C. cystitidis | Bovine bladder and kidney infections |

| C. pilosum | Bovine bladder and kidney infections |

| C. kutscheri | Lung, lymph node, liver, kidney abscesses in rats, mice |

| C. pseudotuberculosis | Ovine and caprine abscesses, lymphadenitis, abortion, arthritis; equine ulcerative lymphangitis, abscesses; bovine abscesses, mastitis (uncommon) |

| C. ulcerans | Bovine mastitis, abscesses: gangrenous dermatitis in rodents |

| C. bovis | Bovine mastitis (rare) |

| C. minutissimum | “Skin scalding” syndrome (tail, brisket, interdigital space in lambs); rare cause of bovine mastitis |

| C. camporealensis | Subclinical ovine mastitis |

| C. mastitidis | Subclinical ovine mastitis |

| C. capitovis | Isolated from skin scrapings of the infected head of a sheep |

| Group D2 | Canine urinary tract infections |

| C. auriscanis | Canine otitis, dermatitis, and vaginitis |

| C. amycolatum | Bovine mastitis (rare) |

| C. testudinoris | Necrotic mouth lesions in tortoises |

DISEASES, EPIDEMIOLOGY, AND PATHOGENESIS

For many members of the genus there is little more information than that presented in Table 8-1, especially regarding pathogenesis.

Corynebacterium renale Group (C. renale, Corynebacterium pilosum, Corynebacterium cystitidis)

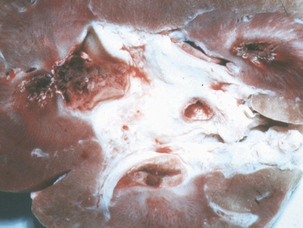

Corynebacterium renale is considered to be normal flora of the lower urogenital tract, and, based upon incidence of disease, is the most important member of the group. Corynebacterium pilosum is also normal flora, and is a less common cause of cystitis and, quite infrequently, pyelonephritis (Figure 8-2). Corynebacterium cystitidis is usually associated with chronic pyelonephritis, but can cause more severe cystitis than the other members of the group; isolation from normal animals is rare.

FIGURE 8-2 Bovine nephritis associated with Corynebacterium renale infection.

(CourtesyRaymond E. Reed.)

Posthitis (pizzle rot, sheath rot) is a form of preputial ulcerative dermatitis that occurs primarily in entire and castrated sheep and goats. The attack rate is rarely greater than 20%, and cases are often sporadic. The etiologic agents are C. pilosum and C. cystitidis, which are normal preputial inhabitants of these animals. Diets high in protein favor production of alkaline urine, with excretion of urea and production of ammonia by urease. This leads to ulceration of the preputial epithelium, with predisposition to secondary bacterial infections. Wethers grazing rich pastures are at risk, as are breeding rams and bucks on high-protein forages. Ewes may develop ulcerative vulvovaginitis after exposure to diseased rams at breeding.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree