Chapter 25 The Genus Brucella

Brucellosis was first described by British physician David Bruce, who in 1886 isolated a bacterium from the spleens of patients with a fatal disease known as Malta or Mediterranean fever. He named the agent Micrococcus melitensis. L.F. Benhard Bang, a Danish veterinarian, recovered what we now know as Brucella abortus from a bovine fetus in 1895. Recognition of brucellosis as a zoonosis in the early twentieth century contributed to establishment of requirements for pasteurization of milk.

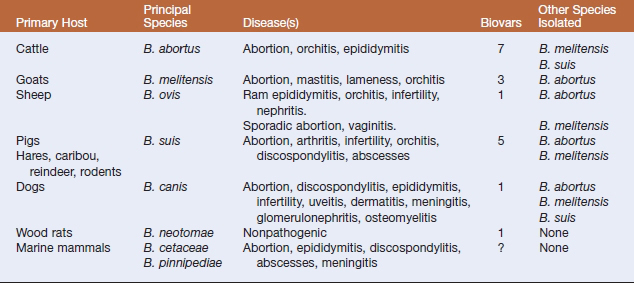

According to the strict phylogenetic definition of a species, taxonomists have proposed that the genus comprise a single species, Brucella melitensis. However, historical precedent has led to retention of the six classical “species,” B. abortus, B. melitensis, Brucella suis, B. ovis, Brucella canis, and Brucella neotomae. Each “species” has a preferred host that serves as a main reservoir for infection (Table 25-1). These have been further divided into biovars based on agglutination by monospecific antisera prepared against A and M lipopolysaccharide antigens, and other phenotypic properties.

DISEASES AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Under appropriate conditions, Brucella can survive outside the host in the environment for extended periods. They may remain viable in carcasses and tissues for up to 6 months at approximately 0° C. They survive up to 125 days in dust or soil, and for as long as 1 year in feces. Brucellae are susceptible to many disinfectants, including 1% sodium hypochlorite, phenolics, 70% ethanol, iodophors, glutaraldehyde, and formaldehyde. The presence of organic matter or use in low temperatures may greatly reduce the efficacy of the disinfectant. The organisms are physically inactivated by moist heat (121° C, ≥15 minutes) and by dry heat (160°-170° C, ≥1 hour).

Brucella melitensis most commonly infects sheep and goats. The organism is regarded as the most virulent of the Brucella species and accounts for most cases of human brucellosis. It has occasionally been isolated from camels and alpacas. Disease is endemic in the Middle East, the Iberian Peninsula, China, the former Soviet Union, parts of Africa, and Latin America. The epidemiology and pathogenesis are similar to that of B. abortus. The main risk factors are contact with contaminated genital discharges and ingestion of raw milk. Sexual transmission is more frequent than in bovine brucellosis. Breed susceptibility is variable in sheep, but goat breeds are highly susceptible. Some animals may spontaneously recover from infection, but the majority remain chronic carriers. Clinical signs include abortion, mastitis, lameness, and orchitis.

Brucellosis in humans is known as undulant fever because of fluctuations in body temperature that are characteristic of the disease. It is an occupational disease of veterinarians, abattoir workers, laboratorians, and farmers. All brucellae are potentially pathogenic for humans, but B. abortus, B. melitensis, B. canis, and B. suis are responsible for most clinical disease. Ruminants are the primary reservoirs for human infection and the most common mode of transmission is consumption of unpasteurized dairy products. Other routes of infection are contamination of abraded or unbroken skin, inhalation of infectious aerosols, and contamination of conjunctiva or other mucous membranes. The infectious dose by the inhalation route has been estimated at 10 to 100 organisms. The incubation period is variable, ranging from 5 days to 2 months. Human brucellosis is a systemic illness with an acute or insidious onset. Symptoms include intermittent fever, chills, sweating, headache, arthralgia, and weakness. Subclinical infections are frequent. Localized suppurative infections may also develop. The case fatality rate in untreated cases is less than 5%, and the relapse rate is high. Person-to-person transmission is very rare because humans tend to be dead-end hosts.