Chapter 18 The Genus Bordetella

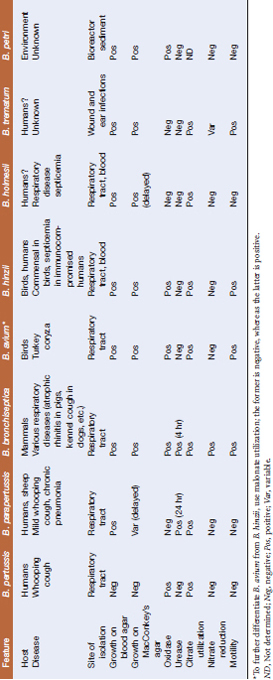

The genus Bordetella is taxonomically assigned to the family Alcaligenaceae within the β-Proteobacteria and is most closely related to the genera Achromobacter and Alcaligenes. These small gram-negative rods were named for Jules Bordet, who first cultivated the type species, Bordetella pertussis. The seven additional species are Bordetella parapertussis, Bordetella bronchiseptica, Bordetella avium, Bordetella hinzii, Bordetella holmesii, Bordetella trematum, and the recently characterized Bordetella petri (Table 18-1). Most Bordetella spp. occur exclusively in close association with mammals and birds. All are catalase positive and asaccharolytic. Optimal growth is at 35° to 37° C, under aerobic or facultatively anaerobic, nonfermentative conditions.

DISEASE AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Bordetella bronchiseptica is one of the agents involved in the infectious canine tracheobronchitis or “kennel cough” complex of young dogs. Older naïve animals are also susceptible. The organism is an important secondary invader following dis temper virus infection, where it is often responsible for a fatal bronchopneumonia. The incubation period for kennel cough is 5 to 10 days, followed by acute onset of a harsh, dry, “honking” cough that is aggravated by excitement or activity. Coughing episodes are often followed by gagging and retching, in attempts to clear mucus from the trachea. The cough can be easily elicited by tracheal palpation. The disease spreads rapidly among closely confined animals, as in boarding kennels or animal hospitals, and the primary infection is often self-limiting. Puppies may shed B. bronchiseptica for up to 3 months after infection, and relapses may follow stress and exposure to adverse environmental conditions.

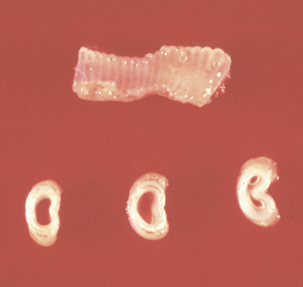

The organism exhibits a strong tropism for the ciliated epithelium of the upper respiratory tract. Turkey poults 1 to 6 weeks old experience an acute onset of sneezing, accompanied by open-mouth breathing, conjunctivitis, nasal discharge, moist rales, anorexia, and altered voice. Stunted growth, tracheal collapse (Figure 18-1), and predisposition to other diseases may result. Morbidity may approach 100%, but mortality is usually low in the absence of secondary infections. In older turkeys and chickens, clinical signs are less severe. The most significant necropsy finding in severely affected birds is dorsoventral collapse of tracheal rings with accumulation of a mucopurulent exudate in the tracheal lumen (see Figure 18-1).

FIGURE 18-1 Flattening of tracheal rings, associated with Bordetella avium infection in turkey poults.

(Courtesy J. Glenn Songer.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree