Chapter 13 The Genera Escherichia and Shigella

The genera Escherichia and Shigella are class γ-proteobacteria, in the order Enterobacteriales and family Enterobacteriaceae.

THE GENUS ESCHERICHIA

Diseases and Epidemiology

Escherichia coli are primary pathogens causing enteritis and septicemia in a variety of domestic species, including poultry, pigs, ruminants, dogs, cats, horses, and rabbits. Other important diseases are ruminant mastitis, canine pyometra and cystitis, and oomphalitis in young chicks. Infections may be endogenous or exogenous in nature. Extraintestinal disease is generally caused by the animal’s normal microbial flora, whereas strains causing gastroenteritis are usually from an exogenous source.

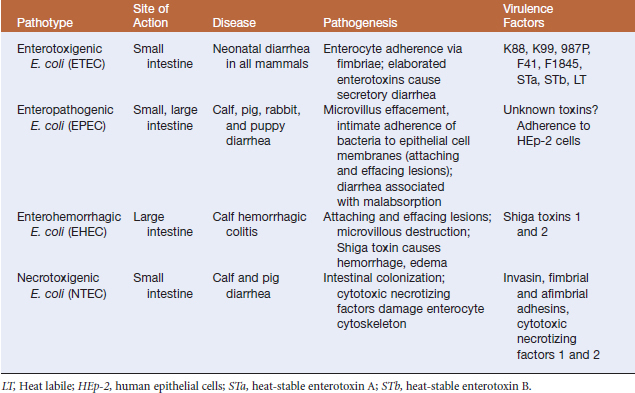

Strains of E. coli associated with disease in the gastrointestinal tract are classified based on virulence properties (Table 13-1). At least six different groups or pathotypes are recognized, including enterotoxigenic (ETEC), enteropathogenic (EPEC), enterohemorrhagic (EHEC), necrotoxigenic (NTEC), enteroinvasive (EIEC), and enteroaggregative (EAggEC). EAggEC and EIEC strains have not been reported from domestic animals. The former is associated with persistent diarrhea in humans in developing countries. Food- or water-borne outbreaks of human diarrhea have been attributed to EIEC.

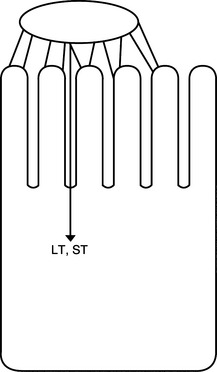

ETEC strains are generally species specific (Figure 13-1). They adhere via fimbriae and elaborate cytotoxins. In neonatal mammals they cause acute, watery diarrhea that may be followed by terminal bacteremia and remain an important cause of economic loss for cattle and swine producers. Clinical signs include white, yellow, or gray scours that occur during the first week of life, and microscopic examination of distal jejunum and proximal ileum reveals bacterial colonization of the mucosal epithelium, without villus atrophy. Some ETEC strains express K88 or F18 fimbriae, colonizing small intestine and producing diarrhea in recently weaned pigs. The common fimbrial adhesins and serogroups associated with disease are in Table 13-2.

TABLE 13-2 Fimbrial Adhesins and Serogroups Associated with ETEC in Domestic Animals

| FimbriaI Adhesin | Animal Host | Serogroups |

|---|---|---|

| K88 (F4) | Pig | O8, O141, O147, O149 |

| K99 (F5) | Pig, calf, lamb | O8, O9, O20, O107 |

| 987P (F6) | Pig | O9, O20, O141 |

| F41 | Pig, calf | O9, O101 |

| F18 | Pig | O138, O139, O141 |

| F1845 | Calf | O101 |

| F17 | Calf, lamb, kid |

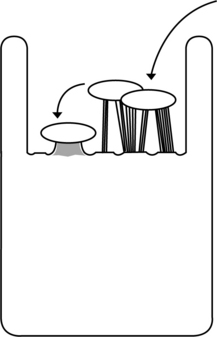

EPECs (Figure 13-2) are isolated from humans and farm animals, as well as dogs, cats, and rabbits, in all of which they produce attaching and effacing lesions. Strains are emerging as important causes of diarrhea in puppies and in other animals, and are associated with “failure to thrive” syndrome. Diarrhea is often mucoid and chronic, as opposed to the watery diarrhea associated with ETEC. Histologically, attaching-effacing lesions are the hallmark of disease.

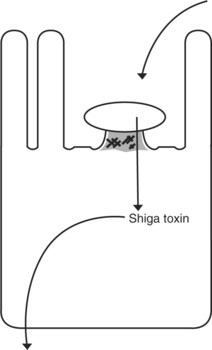

Many EHEC strains (Figure 13-3) produce Shiga toxin, which is similar to the cytotoxin of Shigella dysenteriae O1. These strains are often referred to as Shiga toxigenic E. coli(STEC) or verotoxigenic E. coli(VTEC), with the latter name derived from toxin effects on vero cells in culture. EHEC and STEC are important causes of diarrhea in calves less than 8 weeks of age. Affected animals exhibit mucoid to bloody diarrhea that is rarely fatal, but leaves calves dehydrated, weak, and stunted.

Edema disease, also known as “gut edema” or “bowel edema,” is a communicable enterotoxemia that results in significant death losses in recently weaned pigs. It is caused by EHEC-like bacteria that have acquired the genes for production of a Shiga toxin variant called Stx2e. Strains carrying the F18ab fimbrial type, originally described as F107, are most often associated with this condition. Unweaned pigs may acquire infection in the farrowing house, but lack of full expression of the F18 receptor in piglets younger than 20 days of age augurs against disease in neonates. Clinical signs include ataxia, paddling, confusion, palpebral edema, and sudden death. Postmortem examination reveals edema in colonic mesentery, submucosa of the glandular cardiac portion of the stomach, gallbladder and small intestine, and areas of cerebellar hemorrhage. Adherent gram-negative rods are seen in small intestine, and degenerative angiopathy in small arteries and arterioles, swelling of endothelial cells, and focal encephalomalacia in brainstem are common.

Escherichia coli is the organism recovered most frequently from the infected uterus of dogs and cats. Pyometra occurs more commonly in dogs than in cats. Affected bitches tend to be middle aged or older, whereas younger queens may develop disease. Canine and feline pyometra most often develops during the luteal phase of the cycle or after the administration of progestins. Examination of isolates recovered from cases of pyometra are similar to corresponding fecal isolates, suggesting that fecal contamination of the vaginal vault may be a predisposing factor. Clinical signs in bitches may include vaginal discharge, anorexia, lethargy, polyuria, polydipsia, and vomiting. Vaginal discharge and abdominal bloating are the most common signs in cats. Septicemia and endotoxemia may be sequelae in untreated animals.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree