Chapter 107The European Thoroughbred

Comparisons with Racing in North America

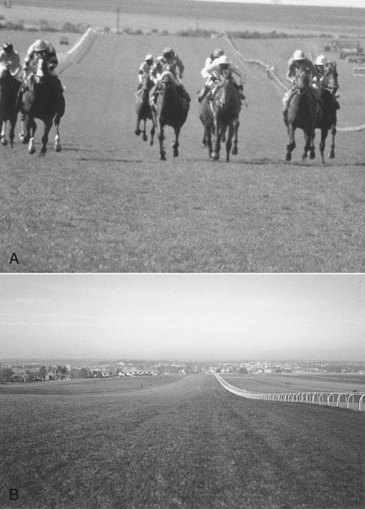

In North America, almost all training and racing takes place on a left circle (counterclockwise), and this might be expected to have influences on the incidence rates of injury to the left and right limbs for many lesions, such as proximal sesamoid bone (PSB) fractures, third metacarpal (McIII)/metatarsal (MtIII) bone condylar fractures, and tendonitis (see Chapter 106). In the United Kingdom, much conditioning work and even race speed training take place in straight lines (Figure 107-1). Racing itself can be on straight tracks (e.g., 1000 and 2000 Guineas at Newmarket), predominantly to the left (Epsom Derby), or to the right (Doncaster St. Ledger). The tracks themselves divide into about one third right-handed and two thirds left-handed throughout the country. This has an important impact on the lack of specific incidence of injury to the left or right limbs. One large fracture survey in Newmarket showed few instances of left or right dominance for any injury.1

Clinical History

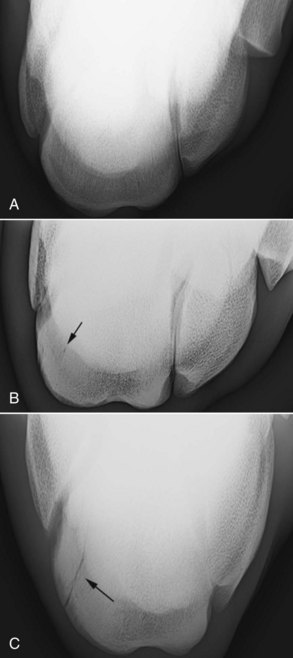

In horses with acute-onset, severe lameness, questions of clinical history become less important because the horse is often not bearing weight, and a suspicion of skeletal failure is raised. Knowing whether this horse has been a good mover before onset of severe lameness is often helpful because some injuries (McIII/MtIII bone condylar fractures, PSB fractures) often are associated with poor gait before the actual fracture takes place. The same is true of horses with slab fractures of the third carpal bone, which often are preceded by a long period of subchondral bone sclerosis associated with bilateral third carpal bone pain (Figure 107-2). One of the most useful questions to ask about a horse with severe lameness is what stage of training the horse has reached because only advanced training to fast canter or gallop speeds usually results in bone failure. However, bacterial infection subcutaneously or within the hoof also can produce severe lameness.

Clinical Examination

Having ascertained which limb is the lamest, the limb should be examined in detail using basic examination protocols (see Chapters 4 through 8 and 10). The following specific points apply to the TB racehorse.

Imaging Considerations

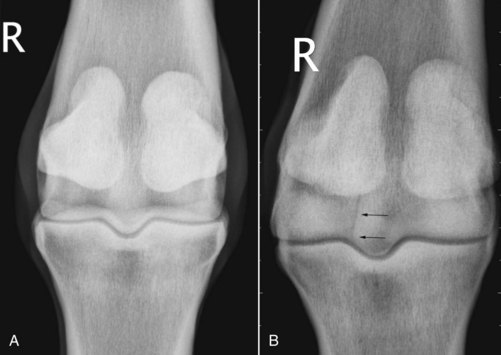

Radiography and Radiology

Radiography is notoriously unreliable in detecting early fracture lines and subchondral bone collapse. For this reason, if lameness is linked to a particular site by diagnostic analgesia and nothing is visible radiologically, repeating the radiography 2 weeks later is often advisable. Any horse with subtle changes in bone density can be rested long enough where additional damage can be seen. During investigation of individual joints, special projections are often most useful (Figure 107-4). Radiographic examination of the metacarpophalangeal and metatarsophalangeal joints always should include the flexed dorsopalmar image, which is extremely useful for evaluating the palmar and plantar aspect of the condyles (see Figures 107-4 and 107-5).3,4 In a hindlimb this view often is achieved best as a plantarodorsal image. The limb is cupped loosely by a hand underneath the tarsus and allowed to hang in a semiflexed position. The cassette is placed in a cassette holder and positioned on the dorsal aspect of the metatarsophalangeal joint, and the x-ray machine is positioned above and behind to achieve the orthodox 125-degrees image.

The lateral condyle of the MtIII bone is a predilection site for subchondral bone injury, represented by sclerosis in the early stages and subchondral bone loss and radiolucency as the condition advances. This can be highlighted by a dorsal 30° proximal 45° lateral–plantarodistal medial oblique image (down angled oblique) developed by Ross5 (see Figure 107-5, C).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree