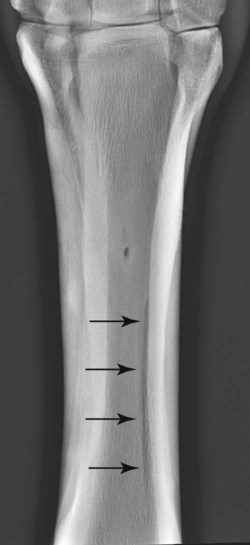

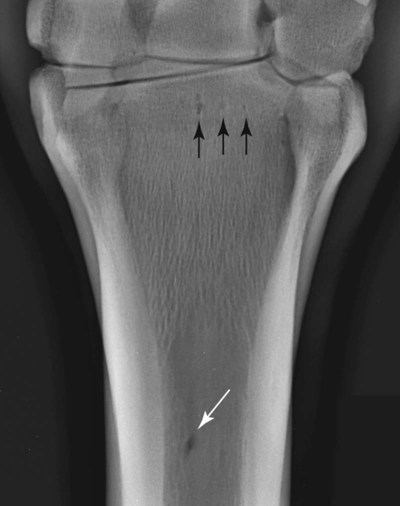

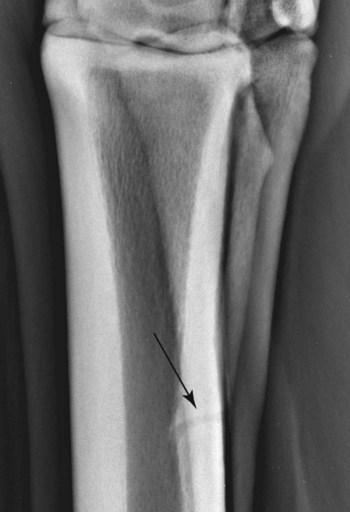

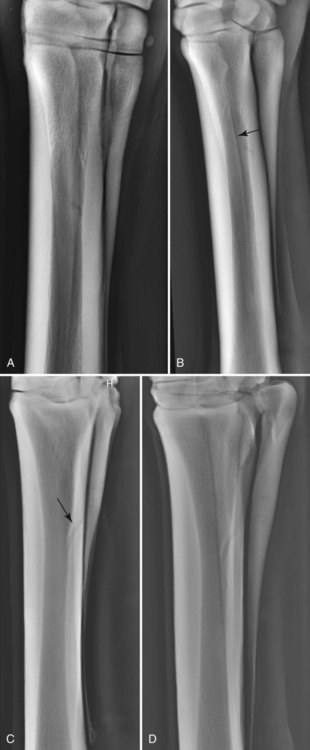

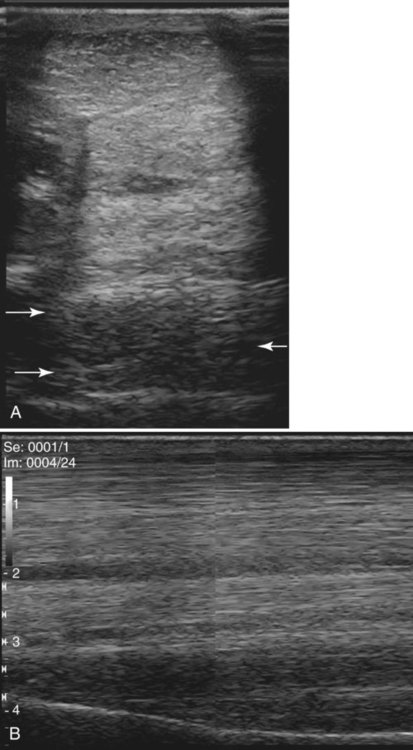

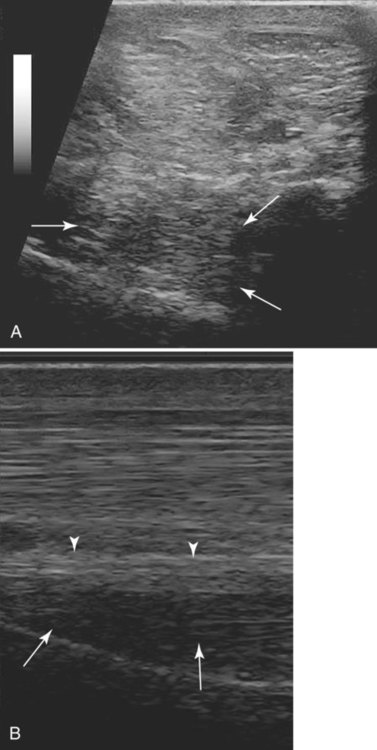

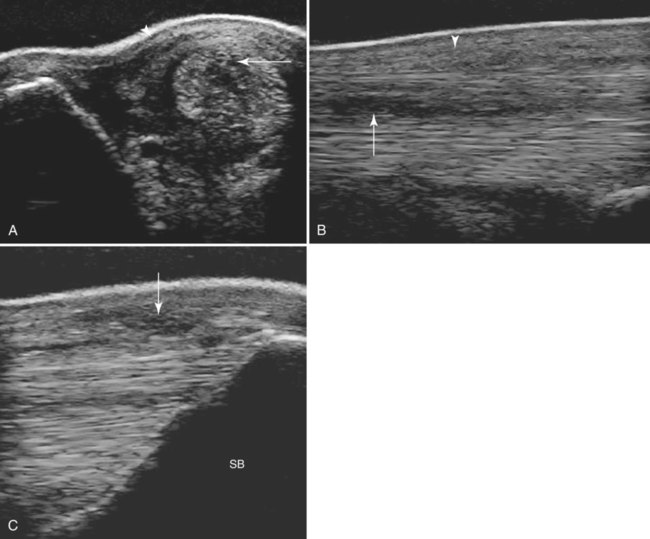

The metacarpal and metatarsal regions are discussed together except where major anatomic differences occur. The osseous structures comprise the second, third, and fourth metacarpal (metatarsal) bones with interosseous ligaments joining the second and third, and fourth and third metacarpal (metatarsal) bones. There is variable ossification of these syndesmoses. In a necropsy study of 100 horses of mixed breed, age, and work discipline, the majority had some degree of ossification between the second or fourth metacarpal bone and the third metacarpal bone, which was often bilaterally symmetric and more extensive medially.1 Five patterns of ossification were recognized, alone or in combination: (1) a small (<1 cm diameter) raised patch of bone that crossed the bone surfaces abaxially, following the line of the fibers of the interosseous ligament; (2) ossification of the interosseous ligament following the line of the fibers; (3) diffuse abaxial proliferation of bone (>1 cm diameter); (4) focal axial ossification of the interosseous ligament on the palmar surface; and (5) diffuse axial ossification on the palmar surface so that the bone margins were obscured. These variable patterns of ossification of the interosseous ligaments were age-related and may reflect a continuum, the result of repetitive trauma, but are not necessarily of clinical significance. In forelimbs the second carpal bone and a variable portion of the third carpal bone usually articulate with the second metacarpal bone,1 whereas the fourth carpal bone articulates with the fourth metacarpal bone. This has biomechanical implications, with forces mediated through both the second and third carpal bones being transmitted through the second metacarpal bone and the syndesmosis with the third metacarpal bone. In hindlimbs the combined first and second tarsal bone articulates with the second metatarsal bone, and the fourth tarsal bone articulates with the fourth metatarsal bone. The interosseous muscle (known colloquially as the suspensory ligament) originates principally from the proximopalmar (plantar) aspect of the third metacarpal and metatarsal bones respectively, with an accessory head that originates from the palmar distal aspect of the third carpal bone in the forelimb2,3 and from the fourth tarsal bone and calcaneus in the hindlimb.4 There are additional fibers from the axial aspect of the fourth metacarpal and metatarsal bones.2,3 There are two lobes of the suspensory ligament proximally that contain variable amounts of muscle and adipose tissue.3,5,5 In hindlimbs, a dense fascial band runs between the second and fourth metatarsal bones on the plantar aspect of the suspensory ligament proximally. In the distal third of the metacarpal region, the suspensory ligament divides into lateral and medial branches that insert on the lateral and medial aspect of the proximal sesamoid bones, respectively. The suspensory ligament branches are closely related to the palmar (plantar) pouch of the metacarpophalangeal (metatarsophalangeal) joints,7 having a subsynovial location distally. Small ligaments extend from the distal aspect of the second and fourth metacarpal bones and merge with the medial and lateral branches of the suspensory ligament, respectively. The accessory ligament of the deep digital flexor tendon originates from the palmar aspect of the third and fourth carpal bones8 and merges with the deep digital flexor tendon in the third quarter of the metacarpal region. In the hindlimb the accessory ligament of the deep digital flexor tendon originates from the plantar aspect of the ligament between the calcaneus and the central and third tarsal bones and is much more variable in size than in the forelimb. It may be bifid or trifid but is sometimes absent.9 In the proximal third to half of the metacarpal and metatarsal regions, the accessory ligament of the deep digital flexor tendon is within the carpal or tarsal sheath. In the proximal quarter of the metacarpal region the dense carpal retinaculum overlies the superficial digital flexor tendon. In the distal one third of the metacarpal region, the superficial and deep digital flexor tendons are contained within the digital flexor tendon sheath, which is reinforced on the palmar (plantar) aspect by the palmar (plantar) annular ligament, which attaches to the abaxial aspects of the proximal sesamoid bones. The tendonous and ligamentous structures change in their relative shapes and sizes from proximal to distal; absolute sizes vary between breeds and sizes of horses, but the relative sizes remain similar. Superimposition of two bones often results in a radiolucent line adjacent and parallel to the margin of one bone. This is a Mach line, and such lines are particularly common in the metacarpal and metatarsal regions, especially when the second or fourth metacarpal bone is projected over the third metacarpal bone (Fig. 21-1). Nutrient vessels are present in the metacarpal and metatarsal bones at standard sites. Nutrient foramina in the proximal epiphyseal region of the third metacarpal bone are seen as small circular radiolucent areas in a dorsopalmar radiograph (Fig. 21-2). The entrance of the principal nutrient vessel is in the middle third of the third metacarpal bone and appears as a circular or oval radiolucent area in a dorsopalmar image (see Fig. 21-2). In oblique images the nutrient canal may be seen as a broad, curved radiolucent line traversing the second or fourth metacarpal bones, which should not be confused with a fracture (Fig. 21-3). The proximal epiphyseal and metaphyseal regions of the third metacarpal bone have a conspicuous trabecular architecture and are often more radiopaque in a dorsopalmar image than the diaphyseal region of the bone (Fig. 21-4). A radiolucent area may be present in the proximal aspect of the second metacarpal bone, especially in association with the presence of a first carpal bone10 (Fig. 21-5). Less commonly there may be a radiolucent area in the proximal aspect of the fourth metacarpal bone, but this may not be associated with the presence of a fifth carpal bone. The base of the fourth metacarpal bone sometimes has a proximal extension10 (Fig. 21-6, A). Similar modelling has been seen on the proximal aspect of the fourth metatarsal bone (Fig. 21-6, B). Nutrient vessels in the second and fourth metacarpal bones are seen with variable clarity. If there is no mineralization of the interosseous ligaments, the margins of the second, third, and fourth metacarpal (metatarsal) bones are smoothly marginated (Fig. 21-7). Smooth or irregularly outlined exostoses on the second and fourth metacarpal bones are common incidental variants (Fig. 21-8, A and B), as are partial mineralization or ossification of the interosseous ligaments, especially medially (Fig. 21-8, C). These variably sized and shaped exostoses (splints) between or around the second and third or fourth and third metacarpal bones may be uniform in radiopacity or have heterogeneous opacity. Some exostoses are associated with long-term increased radiopharmaceutical uptake, despite generally being of no clinical significance. In hindlimbs there may be a large focal irregularly marginated exostosis on the lateral proximal aspect between the third and fourth metatarsal bones (Fig. 21-8, D). Such exostoses appear to occur in a characteristic location, may be unilateral or bilateral, and are always associated with focal intense increased radiopharmaceutical uptake, but generally do not appear to be of clinical significance. There is a variably sized and shaped protuberance on the distal aspect of the second and fourth metacarpal and metatarsal bones (the button of the splint bone), which is present as a separate center of ossification in a neonatal foal. Smoothly marginated enlargement of this protuberance may reflect previous trauma. Bowing of the distal one third of the second and fourth metacarpal bones away from the cortex of the third metacarpal bone is usually the result of previous suspensory ligament branch injury. In a dorsoplantar radiograph of the proximal metatarsal region, it is common to see a linear axial region of increased radiopacity in the third metatarsal bone and/or a mild generalized increased radiopacity of the proximolateral aspect (see Fig. 21-4, B and C). These reactions probably reflect chronic stress at the enthesis of the suspensory ligament but are not necessarily associated with active desmopathy. Acute and chronic injuries of the proximal third of the suspensory ligament are common causes of both forelimb11,12 and hindlimb13–15 lameness, and ultrasonography is the imaging modality of choice, although its sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of hindlimb injuries has recently been challenged.16 However optimization of ultrasonographic technique may facilitate injury diagnosis.17 Ultrasonographic abnormalities include enlargement, a convex palmar (plantar) border, focal or diffuse hypoechogenic areas, poor definition of the margins, most particularly the dorsal margin, and reduced strength of fiber pattern in longitudinal images (Figs. 21-9 and 21-10). With chronic injuries there may be areas of increased echogenicity reflecting fibrosis and chondroid metaplasia and occasionally dystrophic mineralization; periosteal irregularity may also be detected. Osseous changes may be seen radiologically in association with chronic suspensory desmopathy and include generalized or focal increased opacity reflecting stress at the enthesis and entheseous new bone (Fig. 21-11, A), or increased opacity of the endosteal bone of the proximal palmar (proximal plantar) aspect of the third metacarpal (metatarsal) bone. Entheseous new bone is best seen in a dorsopalmar (dorsoplantar) image (Fig. 21-11, B), whereas increased opacity of the endosteal bone is best seen in a lateromedial image. Nuclear scintigraphy may reveal increased radiopharmaceutical uptake in the proximopalmar (proximoplantar) aspect of the third metacarpal (metatarsal) bone in the absence of detectable radiographic abnormality in association with either acute, severe, or chronic injuries18,19 (Fig. 21-11, C). Computed tomography20,21 or magnetic resonance imaging16,22–25 is sometimes necessary to identify lesions of the suspensory ligament or adjacent osseous reactions. An axially projecting exostosis from the second or fourth metacarpal bones may impinge on the suspensory ligament and cause focal desmitis. Echogenic material can sometimes be seen extending between the exostosis and the suspensory ligament, but occasionally magnetic resonance imaging is required for definitive diagnosis.26 Swelling in the region of a branch of the suspensory ligament may reflect enlargement of the ligament or the periligamentous tissues, or both and accurate determination can be made only by ultrasonographic evaluation from the palmaromedial and palmarolateral aspects of the limb (Fig. 21-12). Because of their superficial location, a standoff is usually required to evaluate the suspensory branches. Injuries may be biaxial; therefore both medial and lateral branches should be evaluated in their entirety, including their insertions on the proximal sesamoid bones. Entheseous new bone on a proximal sesamoid bone is readily detectable ultrasonographically (Fig. 21-12, C), but other osseous changes such as enlargement of vascular channels and some fractures can only be determined radiographically (Fig. 21-13, A). The second and fourth metacarpal bones should also be assessed radiographically; bowing of the distal one-third, fracture at the junction of the proximal two-thirds and distal one-third (Fig. 21-13, B), or generalized enlargement of the distal one-third (see Fig. 21-13, A) are common abnormalities seen in association with suspensory branch injuries. Lesions may extend proximally into the body of the suspensory ligament, which should also be evaluated ultrasonographically.

The Equine Metacarpal and Metatarsal Regions

Anatomy

Normal Radiographic and Ultrasonographic Variations

Abnormalities

Soft Tissue Injuries

Proximal Suspensory Desmitis and Desmopathy

Suspensory Body Injuries

Suspensory Branch Injuries

The Equine Metacarpal and Metatarsal Regions