Chapter 40The Elbow, Brachium, and Shoulder

Diagnosis

Clinical Signs

If lameness is mild, then the character of the lameness is nonspecific; but if lameness is moderate to severe, it is often characterized by a shortened cranial phase of the stride, a reduced height of the arc of foot flight, and a marked head lift and nod. ![]() These gait characteristics are evident at the walk and the trot. Observation of the moving horse from the front and the side is particularly useful. The horse may pivot on the lame limb when turning. The gait characteristics of shoulder slip (see page 473) are more easily identified by observing the horse walking toward you. Lameness is frequently accentuated with the lame limb on the outside of a circle. In horses with proximal limb lameness, especially associated with muscle fibrosis, lameness may be evident only when the horse is ridden, performing specific movements. Manipulative tests of the proximal limb joints are rather nonspecific and frequently unrewarding.

These gait characteristics are evident at the walk and the trot. Observation of the moving horse from the front and the side is particularly useful. The horse may pivot on the lame limb when turning. The gait characteristics of shoulder slip (see page 473) are more easily identified by observing the horse walking toward you. Lameness is frequently accentuated with the lame limb on the outside of a circle. In horses with proximal limb lameness, especially associated with muscle fibrosis, lameness may be evident only when the horse is ridden, performing specific movements. Manipulative tests of the proximal limb joints are rather nonspecific and frequently unrewarding.

Local Analgesia

It is important to recognize the potential effect of a median nerve block, performed in the proximal antebrachium, on elbow pain. Elbow lameness may be substantially improved, presumably because of local diffusion of the local anesthetic solution. Techniques for intraarticular analgesia of the elbow and shoulder and intrathecal analgesia of the intertubercular bursa are described in detail in Chapter 10. Intraarticular analgesia of the elbow and shoulder joints usually improves but rarely eliminates pain associated with either joint. The elbow and shoulder joints are relatively large; therefore use of at least 10 mL of local anesthetic solution (mepivacaine, 2%) is recommended for the elbow joint and 20 mL for the shoulder joint. Retrieving synovial fluid from each joint is usually possible. Absence of resistance to injection is not a guarantee that the needle is in an intraarticular location. Walking the horse after the block facilitates circulation of the local anesthetic solution throughout the joint. Although improvement in lameness may be seen rapidly, within 10 to 15 minutes after injection, at least 1 hour should elapse after the block before the result is considered negative. The block generally is effective for up to 2 hours. The block usually has no influence over pain associated with periarticular structures.

When performing intraarticular analgesia of the shoulder, it is important to recognize that there is communication with the intertubercular bursa in some horses. In some horses instability of shoulder, so-called shoulder slip, appears transiently (for up to 2 hours) after injection of local anesthetic solution. This prohibits interpretation of the nerve block. The cause is presumably diffusion of local anesthetic solution to nerves innervating the muscles responsible for maintaining stability of the shoulder. Positive-contrast arthrography has shown that injection of volumes greater than 20 mL pose a danger of pooling at the site of injection or leakage from the joint capsule.. An experimental study demonstrated that deposition of mepivacaine over the suprascapular nerve could result in transient shoulder slip, but this may be the result of diffusion to affect the brachial plexus (see page 473).3

Imaging

Radiography and Radiology

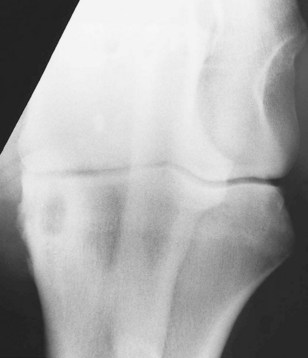

It is important to recognize that the cranial articular margin of the proximal radius has several lips that should not be confused with osteophytes (Figure 40-1). The cranial tuberosity of the proximal aspect of the radius may appear roughened in slightly oblique mediolateral views.

In the scapulohumeral joint a small circular radiolucent region is sometimes seen in the subchondral bone in the middle of the glenoid cavity of the scapula (Figure 40-2). A radiolucent edge effect is often seen in the proximal humerus, the result of superimposition of the lateral rim of the glenoid cavity of the scapula.

Ultrasonography

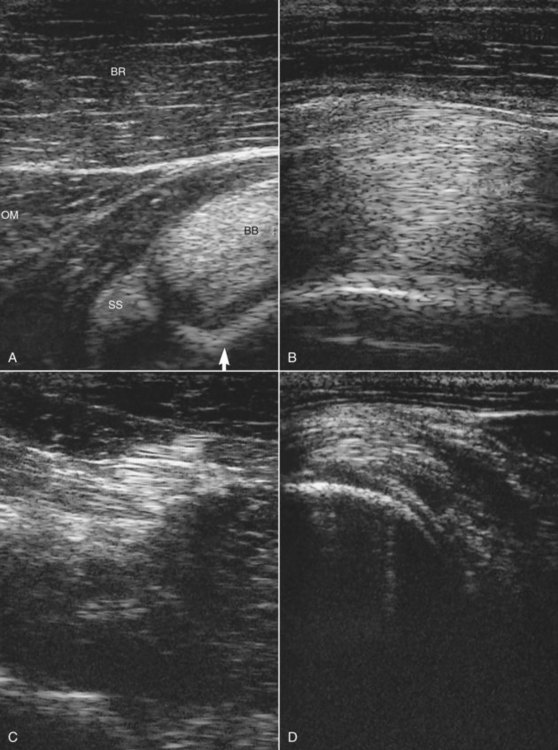

In the shoulder region ultrasonography is important for assessing the intertubercular bursa, humeral tubercles, tendon of biceps brachii (Figure 40-3, A and B), tendons of insertion of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles (Figure 40-3, C and D), and the infraspinatus bursa (Figure 40-3, B).6-10 Care should be taken to ensure that the horse is fully load bearing on the limb, because hypoechogenic artifacts can be created, especially in the tendon of biceps brachii, unless the musculature is under tension. The medial and lateral lobes of the tendon of biceps brachii and the isthmus between them should each be evaluated individually, because getting the entire structure into focus simultaneously is difficult.

Differential Diagnosis

Elbow

Osteoarthritis

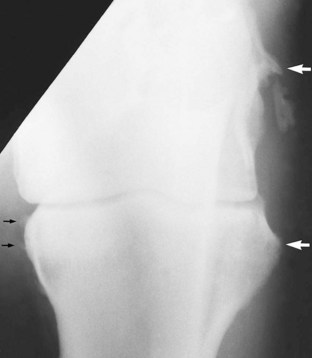

Intraarticular analgesia improves lameness. Periarticular osteophyte formation, alterations in subchondral bone opacity, and narrowing of joint space width may be seen radiologically (Figure 40-4). Care should be taken not to misinterpret as osteophytes normal bony lips on the dorsoproximal aspect of the radius in a mediolateral image.

Osseous Cystlike Lesions

Osseous cystlike lesions occur most commonly medially in the proximal radial epiphysis (Figure 40-5) and usually result in acute-onset, relatively severe lameness in immature athletic horses.

Less commonly, large, less well-defined osseous cystlike lesions have been identified in the distal aspect of the humerus in young Thoroughbreds being prepared for the yearling sales or just after entering training.1 Lameness is acute in onset, persists despite box rest, and is generally not influenced by intraarticular analgesia of the elbow. Nuclear scintigraphic examination reveals a region of IRU in the distal aspect of the humerus, more centrally located than that associated with a stress fracture (see page 463). Careful radiological examination reveals a less well-defined osseous cystlike lesion. Conservative management has resulted in persistent lameness, and the results of surgical treatment have been disappointing. Young horses with smaller osseous cystlike lesions in the distal medial humerus have been identified and have responded to conservative management.12

Collateral Ligament Injury

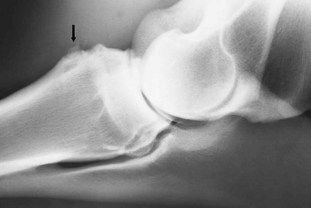

Definitive diagnosis requires ultrasonographic examination and identification of disruption of the normally linear pattern of echoes within the ligament. Sometimes periosteal new bone or avulsion fractures can be identified at the region of ligamentous attachment.16 Radiographic examination should also be performed to identify any concurrent pathological condition of the bone, such as enthesophyte formation, an avulsion fracture, or secondary OA (Figure 40-6).

Enthesopathy of the Biceps Brachii

Tearing of the attachment of the biceps brachii from the cranioproximal aspect of the radius may be associated with a traumatic injury such as a fall, but frequently history does not suggest the cause. Lameness is sudden in onset and often not associated with any localizing signs, except pain on manipulation of the elbow in horses with acute lameness. The lameness has no particular characteristics. The response to local analgesic techniques is negative. Radiographic examination may reveal periosteal new bone on the cranioproximal aspect of the humerus in horses with chronic lameness17 (Figure 40-7). Sometimes an adjacent mineralized fragment is present, an avulsion fracture or dystrophic mineralization. Some new bone formation on the cranioproximal aspect of the radius can be seen in normal horses, reflecting previous injury; therefore care should be taken in interpreting its current clinical significance. Nuclear scintigraphic examination is helpful for acute lameness before periosteal new bone develops and in horses with chronic lameness. Ultrasonographic evaluation has not been helpful. Treatment is by rest. The prognosis is guarded to fair.